Welcome to Dispatches From The Frontier, Multiversity Comics’ “Manifest Destiny” annotations column. There’s a lot to catch up on with this book from Chris Dingess, Matthew Roberts, and Skybound Comics, with the story into its fifth arc and the Corps of Discovery, led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark, already having moved into North Dakota and set up their first winter quarters of the expedition. We’re going to take a look at some of the journey so far, covering the rough story of issues 1 to 26, from the “Flora and Fauna” arc to the current issue, and how that matches up with the historical expedition; put a small spotlight on the Sacagawea, her importance to the expedition and her portrayal here; and then have some speculation on where this current arc is headed.

The Journey So Far:

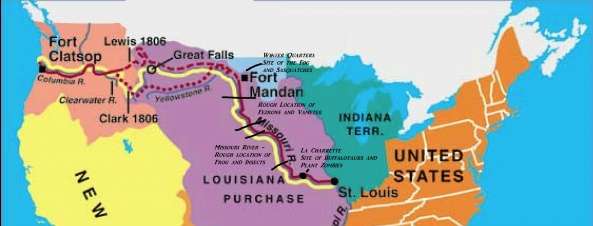

At this point in the book, the Corps of Discovery has made the trip from St. Louis up the Missouri River to the site of their winter quarters in North Dakota. From all indications, it looks like the comic characters have taken roughly the same route as the historical expedition and are now at their winter quarters at Fort Mandan, peacefully coexisting with the neighboring Hidatsa and Mandan tribes while they wait out the winter of 1804/1805.

While a lot of the generals of the story line up with actual historical expedition (rough route, important members, etc), probably the biggest difference besides the obvious presence of monsters is the number of casualties on the expedition. Over the course of the four complete arcs of the comic, many of the members of the Corps have been cut down, eaten, infected, or maimed by buffalotaurs, plant zombies, frog monsters, giant bugs, or the Vameter, really thinning out the ranks of the expedition. This large number of casualties is a big point of unrest among the enlisted troops, making them question the wisdom of the whole expedition and the effectiveness of their leadership.

In the historical expedition, only one man, Sergeant Charles Floyd, would die on the expedition. Though Clark chalked Floyd’s death up to “bilious cholic”, modern researchers think it was much more like a ruptured appendix that killed Floyd, a far less exciting death than the various monsters featured in the comic. Floyd’s death would be the sole death on the expedition, which is quite a feat considering the Corps spent nearly two-and-a-half years traveling over largely unexplored terrain from St. Louis all the way to the Pacific Coast, traversing mountains, rivers, and more in the process.

Interestingly, none of the historical Corps members, other than Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea, Charbonneau, and York, seem to have truly been included in the comic, with only the characters of Collins and Tuttle sharing a last name with historical members of the expedition. In the comic, they have such different roles that it’s likely either coincidence or simply the use of the name for the name’s sake. The rest of the expedition, like Burton, Parker, Imes, and the rest don’t seem to share a name with any historical member and instead seem to have been made purely for the comic and its story.

Also an addition is the presence of convicts in the Corps of Discovery. In the historical expedition, each member of was a volunteer soldier, all healthy, single, and with strong survival and hunting skills. Obviously, with monster hunting on the agenda, having expendable convicts as part of the crew makes sense. It also helps to create a form of conflict among the enlisted men and the conscripted prisoners.

When the historical Corps made winter quarters at Fort Mandan, this would also be the first time they would meet Sacagawea and Charbonneau, rather than having them as part of the expedition since nearly the beginning, as is the case in the comic. The peaceful and fruitful dealings with the local natives that Clark experiences is pretty accurate, with the historical example, as the Corps traded freely with the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes during the winter of 1804/1805.

Continued belowWhere the story goes from here, and how closely it stays to a historical context, is anyone’s guess. This reader hopes it continues to mix the historical and the fantastical with a measured hand, keeping the story grounded just enough to give nods to us history buffs, but also playing with the weird and wild frontier landscape that they’ve created so far in “Manifest Destiny”.

Sacagawea:

Who better to examine in this installment than Sacagawea? Especially given the backup story that focuses on her in issue 25.

Sacagawea, alternately spelled Sakakawea or Sacajawea or a random mishmash of syllables in the various journals kept by Lewis, Clark, and other Corps members, was the Shoshone woman that traveled with the Corps of Discovery from 1804 to 1806, traveling thousands of miles from North Dakota to the Pacific Ocean and back again, and helping greatly with the Corps’ mission of establishing contact with the various Native American tribes that they encountered.

She was born in a Shoshone tribe near present day Salmon, Idaho, in approximately 1788. In 1800, she and several other girls were taken as prisoners after a battle with a tribe of Hidatsa. She and the other girls were then taken to a Hidatsa village near Washburn, North Dakota after their capture and used as slaves and sold as wives.

A couple of years later, Sacagawea was taken as a wife by the Quebecois trapper Toussaint Charbonneau, who was living in the village. While reports varied slightly, Charbonneau was reported to either have bought Sacagawea from the Hidatsa to be his wife or to have won her from gambling.

The Corps of Discovery arrived near the Hidatsa village and built Fort Mandan for winter quarters of 1804-1805. During the winter, they interviewed several nearby trappers who might be able to act as interpreters or guides after they began back up the Missouri River in the spring. They eventually settled on hiring Charbonneau in part because Sacagawea, now pregnant with her first child, was Shoshone and they knew they would have to deal with the Shoshone as they neared the headwaters of the Missouri.

After spending the winter with the Corps at Fort Mandan, Sacagawea would have an eventful 1805. Her child, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, was born February 11, 1805, with Clark and other members of the expedition nicknaming the child “Pomp” and “Little Pompy”. In May, while heading up the Missouri, Sacagawea rescued items that had fallen in the river from a capsized boat, including journals and records of Lewis and Clark. As recognition of her quick action, the Corps commanders named the Sacagawea River after her.

In August, the Corps would come across a Shoshone tribe and intend to trade for horses to cross the Rocky Mountains with. They used Sacagawea as an interpreter and she recognized the chief of her tribe as her brother Cameahwait. The reunion between the two was apparently quite touching and both Lewis and Clark made note of the reunion in their respective journals.

After receiving the horses and crossing the Rockies, the Corps was exhausted and near starving, as they’d been reduced to eating tallow candles to survive during the crossing. Sacagawea would find and prepare roots for the expedition to eat as they descended into the more temperate regions. After this crossing, the Corps would head to the Pacific Ocean and eventually make winter quarters there. During the winter a whale washed up near their winter quarters and Sacagawea insisted on being able to see this “monstrous fish” (A “monstrous fish” is just asking to be a “monster of the arc” of some kind as the Corps gets to the Pacific and gets closer to uncovering the mystery that permeates the book so far). On the return trip, Sacagawea would lead the Corps through Gibbons Pass through the Rockies and into the Yellowstone River Basin through Bozeman Pass, passes the apparently knew about thanks to her travels earlier in life with her different tribes.

Though she’s often credited as a guide for the Corps, she only provided explicit directions in a few instances. Her abilities as translator were, of course, useful and helped the group to navigate what could’ve been disastrous first meetings, but likely her biggest benefit to the group was simply her presence. Most Native American tribes in the areas that the Corps explored didn’t allow women and children to travel with their war parties, so the presence of a young woman and a small child helped to reinforce the peaceful mission that the Corps of Discovery was pursuing. Though they were prepared for any hostilities and armed with some of the most high-tech weapons of the day, the simple act of Sacagawea being with the group likely saved them from tense situations and having to actually use these weapons against the Native Americans that they encountered.

Continued below

After the expedition, Sacagawea and Charbonneau would head back to their home village before taking up Clark’s offer to settle in St. Louis in 1809. The couple would soon after entrust Jean Baptiste’s education to Clark and he would go about enrolling him in school. Sacagawea would also have a daughter named Lizette sometime around 1810.

Historical documents, , such as Clark’s own journals and journals of those living in the same settlement as her at the time of her death, and research suggest that Sacagawea died in 1812 from an unknown illness, though there are various, largely unsupported, oral traditions that say she left Charbonneau, married into a Comanche tribe, before eventually traveling to the Shoshone in Wyoming and may have died as late as 1884. Lizette would die in childhood, while Jean Baptiste would be entrusted into Clark’s care and become something of a celebrity, as he was the child who traveled across the frontier with the Corps of Discovery.

Her role as an elite and seemingly unbeatable warrior in the comic is, obviously, one of the fiction. While she often helped the Corps find food or navigate situations with the natives and surely saved their lives in these roles, it’s not quite so likely that she’d be out killing the buffalotaurs by herself or fending off the other monsters. Of course, Jean Baptiste also didn’t figure into a larger conspiracy of some sort, either, but those changes make for good comics.

Speculation:

After four arcs of the Corps of Discovery fighting various monsters and losing members of the expedition at a pretty steady clip, this arc looks like it may just shine light on some of the worst monsters in the whole book: the Corps itself. This isn’t to say that these men are entirely reprehensible. They’re, mostly, good people, but there’s a darkness that lurks there. They did just slaughter an entire tribe of bird people in their sleep in the third arc, after all.

We know at this point that there’s some sort of relationship between the various beasts being encountered and the presence of an Arch. The Native Americans in the area know this and stay clear of them. The Arch near the Corps’ winter quarters seems to have been felled, so, if the correlation between Arch and monsters is direct, there shouldn’t be anymore beasts to attack them. That said, it looks like the fog is the danger so far in this arc. It seems to have some sort of hallucinogenic/psychotropic qualities, making the the victim see things. As we can see at the end of issue 25, this causes Burton to shoot one of his fellow Corps member in a bit of confusion. Whether the fog is the only danger this arc isn’t clear yet, but I’m thinking it likely will be.

We know that Clark has a violent past because of his military service, something that seems to weigh heavily on him and had driven him to excessive drinking before he sobered up for the expedition. I would be absolutely surprised if we don’t see him out in the fog reliving some horrors before the next couple of issues are over.

Likewise, Lewis has “a darkness inside him”, as other characters have put it. We know, historically, that Lewis also struggled with depression and heavy drinking, especially towards the end of his life. These struggles may even have led to him taking his own life, though that’s highly debated. If Lewis makes his way into the fog, readers may finally get to see the true darkness that lies under that veneer of goodness and academia that he projects. Putting Lewis and Clark out into the fog, and having them experience their personal horrors, could be an interesting turn for the Corps as they watch their so far fearless leaders be consumed by fear.

With issue 26, we see that fog just doesn’t cause the men to see things in each other, but it also seems to bring up all the creatures they’ve killed so far on their journey. In the instance of Wallace, it looks like the fog is making him see the form of Sergeant Parker, who he allowed to be murdered. I’m thinking the monsters in the fog aren’t actually real, but some kind of product of the fog’s hallucinogenic/psychotropic effects. This could be supported by the distorted look of the some of the monsters in the fog, like that of a buffalotaur who looks crossed with a La Charrette plant zombie, and also the inability of some of the Corps members to hit the monsters, despite them all being generally pretty well trained and capable. Of course, that doesn’t mean that those monsters can’t cause real harm to the expedition, especially given how wary the local tribes are of the fog. Between the monsters in the fog and its ability to make those exposed to it see things, I’m thinking this arc will put the Corps through quite a trial, one that tests both their ability to survive and also their ability to distinguish reality from what’s in their mind.