Welcome back to Dispatches From The Frontier, Multiversity Comics’ “Manifest Destiny” annotations column. Following up on the last entry, we’re digging into issue 28 of “Manifest Destiny”, the Skybound Entertainment comic from Chris Dingess and Matthew Roberts that follows Lewis and Clark on their journey to rid the Louisiana Purchase of great and terrible monsters. This is nothing like what they taught you in history class.

The Corps of Discovery is still camped in their winter quarters at Fort Mandan and the fog continues to play havoc among the members of the Corps of Discovery. As has often been the case, it seems like it’s up to Captain Lewis to save the rest of the Corps. We’ll take a look at the journey so far, with a bit of a dive into what exactly the Corps did while wintering at Fort Mandan; shine a spotlight on William Clark, Lewis’ great friend and co-captain of the expedition, in responsibility if not in name; and, finally, wrap up with some speculation on where this issue leaves the Corps and just who that is on the last page.

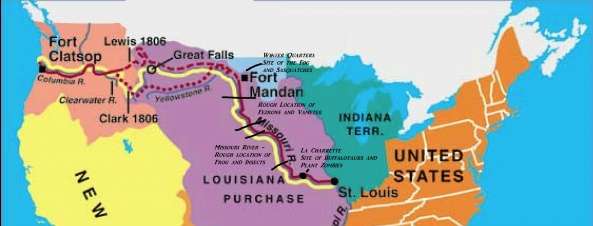

The Journey So Far

The story continues as the Corps of Discovery waits out the winter in Fort Mandan, their winter quarters of 1804/5 in what is now North Dakota. The Corps continues to battle the strange visions they’re seeing due to the fog that has rolled in at the beginning of the arc. Friend is fighting friend as they see each other not as the men they’ve grown to know, but as the various monsters they’ve had to fight to survive along their journey.

This issue finds the Corps doing much of the same stuff as last issue, mainly trying to kill each other. Clark and Sacagawea are involved in a one-on-one fight with each trying to kill the other, and Lewis seeming to think the American soldier and the Shoshone woman are equally matched in fighting skill. York and Reed are finally starting to feel the influence of the fog in their quarantined quarters as York sees the figure of a man from his past and Reed begins to see York as a plant zombie. Lewis and Mrs. Boniface are still trying to figure out which plants make Lewis immune to the fog and how to get those plants into the systems of all the various members of the Corps of Discovery without them killing Lewis. While things rarely go easy for the Corps of Discovery on this journey, they’re not looking great right now.

The actual stay at Fort Mandan was much, much less dramatic, but no less exciting. This was one of the first times that such a large group of Americans had the chance to live and work alongside Native Americans in this part of North America. The Corps spent the months in Fort Mandan trading supplies, restocking their food, and taking part in various customs and festivals of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes that were nearby. The men of the Corps, as recorded in different journals, found their way to the beds of the Mandan and Hidatsa women more than once, exchanging more than just supplies and food with them.

Arguably the most important thing that the Corps got from their stay at Fort Mandan was knowledge of what was further downriver. At the time, the maps the Corps had essentially ended near the site of Fort Mandan in North Dakota. What was beyond that was more conjecture and guess than anything concrete. Thomas Jefferson had books at the time that said wooly mammoths still roamed the wilds of North America beyond the Mississippi and that made about as much sense as anything else to the Americans because no white people had really explored most of it. Of course, the Mandan and Hidatsa, and other tribes that passed through the area, traded further down the Missouri, along with having ideas of what came after that. The knowledge that Lewis and Clark gained of the lay of the land helped them have an idea of where they were going as they set out from Fort Mandan the following spring. While they would fill in the map as they went and create one of the most complete maps of the interior United States of their time, being able to know which split in the river to take or where they could count on food being plentiful was invaluable to the Corps.

Continued belowCharacter Spotlight: William Clark

I feel like William Clark is often overshadowed by Meriwether Lewis when it comes to talking about the Corps of Discovery in a historical context. Maybe it’s the tragic story of Lewis post-journey, where he battles depression and alcoholism is either murdered or commits suicide while traveling, that Lewis was essentially Thomas Jefferson’s surrogate son, or that Lewis was the only person officially designated a captain on the journey, but Lewis often seems to get more of the credit. Not to say that Lewis doesn’t deserve the credit, as Jefferson personally chose him to oversee the expedition, but Clark played an extremely important role both in the expedition and also in the later years as he developed and guided the course of actions that the still young country would take as it sought to claim more and more land and had to deal with the people already living there.

William Clark was born in 1770, the ninth of tenth children to a modestly wealthy Virginia family that owned an estate and a few slaves. While William was too young to fight in the American Revolution, his five older brothers all served with his two oldest brothers, Jonathan and George Rogers, both serving in militias and achieving the ranks of colonel and general, respectively, during the war. After the war, Jonathan and George Rogers would arrange for their parents and younger siblings to move to frontier in Kentucky, where William would spend most of his teenage years. It was in Kentucky that George Rogers would teach William the survival and hunting skills that would later aid him in his own military career and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

While in Kentucky, Clark would start his military career in earnest. In 1789, at age 19, he would join up with a Kentucky militia force to take part in the Northwest Indian War, a conflict with various Native American groups who were seeking to preserve their land north of the Ohio River. Clark would start keeping a detailed journal of his activities around this time, something that he would continue for most of the rest of his life and would serve him well during the Corps of Discovery’s journey to the Pacific.

It was in these early militia days that Clark and the militia he was a part of would kill 8 men, women, and children in an attack on a peaceful Shawnee hunting camp, something that seemed to have an effect on him in later years. For the next several years, Clark would play various roles in the Indiana Militia and the Legion of the United States, with him reportedly traveling to the Southeast to meet with the Creek and Cherokee to keep them out of the war, among other things. In 1794, he’d command troops at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and help bring a decisive victory that would end the Northwest Indian War. It was also during the Northwest Indian War that he would meet Meriwether Lewis, with Clark serving as his commanding officer. The two would become good friends and Clark would impress himself on Lewis so much that Lewis would think of Clark above all others when it came time to choose a co-commander of the eventual journey to the Pacific.

Though only 26, Clark would retire from the military in 1796 citing “poor health”. He would return to his family’s plantation near Louisville and live a mostly quiet life for the next several years. When the time came for Lewis to put together his expedition to the Pacific, he immediately wanted to recruit Clark, then 33, to act as his co-commander on the expedition. Though military decorum at the time dictated that there could only be one commander and the Senate refused to appoint Clark as a captain, Lewis insisted that Clark serve with equal authority and most of the expedition never knew that Lewis actually outranked Clark, despite only being a second-lieutenant to Lewis’ captain. Clark’s years spent fighting and negotiating with Native Americans during the Northwest Indian War would serve him well, as he and Lewis would often have to meet with chiefs of the tribes they encountered along their journey, bartering for goods and safe passage. Many sources state that Clark was always the more comfortable of the two around Native Americans, with him a sort of respect for them that Lewis may not have had.

Continued belowWhile Clark and Lewis shared many duties of the expedition, they also played to their strengths. Clark’s military career made him a natural choice as the one to update and create the maps that the expedition would use along the way, going on to create possibly the most complete maps of the interior of North America of the time. His previous experience as a quartermaster made him a natural at managing the expedition’s supplies over the multi-year journey. His survival skills honed on the frontiers of Kentucky also meant that he often led the hunting expeditions that kept the expedition fed throughout the journey. Clark continued his longstanding practice of keeping a detailed journal throughout the expedition, with his journal recording many events or documenting new animals that Lewis and others neglected to mention. Like many of his time, Clark lacked an extensive formal education and American English spelling wasn’t really formalized at the time, so his journal often has the same word spelled many, many different ways. For example, he would spell “Sioux” about 27 different ways throughout his journals. Still, he was an intelligent and well-read man, even if he was often self conscious of his often inconsistent grammar and spelling.

In the years after the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Clark would be appointed to various governmental roles, from the governorship of the Missouri territory to appointments in various Native American- specific government departments, eventually ending with the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, that almost all relied chiefly on his experiences as a soldier, explorer, and knowledge of the Native Americans. It’s in his later roles of working on policy concerning Native Americans that his time spent both fighting Native Americans and documenting their culture and language would often clash.

Clark’s actions during his time as Superintendent of Indian Affairs have often been described as those of a strict father. He wanted to see Native Americans succeed, but also had a certain way he thought that possible. He genuinely seemed to care about the Native Americans that fell under his authority, seeking to preserve their culture, language, and customs as he saw them getting closer to extinction. He gave them access to medicine and inoculations, he attempted to better their overall lives. At the same time, he was also a former soldier who was around when the country was birthed, giving him a very strong loyalty to the United States. He upheld Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, fought to immerse the Native Americans in white culture rather than leave them be, and thousands upon thousands of acres of land were taken from Native Americans during his tenure. He seems like a contradiction, but he was more lenient on Native Americans than most were at the time, for whatever that’s worth. It’s quite possible that without the experiences that he gained among the Native Americans during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, things could’ve been much worse for the Native Americans he decided policy on.

Clark would hold his superintendent position until his death in 1838. He was the last major member of the expedition alive.

Speculation:

The big mystery with this issue is who or what is the figure in the fire? Easy money says that the hooded, horned figure is merely a group hallucination brought on by the fog. But that seems too easy, doesn’t it? We’ve already seen that pretty much each member of the Corps has a different hallucination caused by the fog – some are seeing buffalotaurs, some are seeing plant zombies, some the Fezron, Mrs. Boniface sees her dead husband, Clark sees Blue Jacket and other hostile Native Americans, York apparently sees a former slave overseer. Also, it looks like Lewis himself set the cabin on fire, with the various plants inside, in order to have the various Corps members help put out the fire, breathe in the smoke, and cure themselves of the hallucinations. So, surely the skeletal figure isn’t actually real and is just yet another of the hallucinations caused by the fog, right? I can honestly go either way on this. The fog doesn’t seem to really do group hallucinations, so it would make sense for the skeletal figure to be real, especially as each Arch so far has had a physical component to the danger of it – an actual monster. On the other hand, revealing the “monster of the arc” this late seems iffy. Plus, it’s unsure where the skeleton monster could’ve actually came from, seeming to spring from a fire that Lewis theoretically started. I don’t know, y’all.

I’m still waiting for/hoping that the fight with Clark causes Sacagawea to go into labor, if for no other reason than it would better line up with the historical timeline of her having Jean Baptiste during the winter at Fort Mandan. I know this is largely fiction at this point, but I still like just a *touch* of historical accuracy.

The reveal that York has apparently killed a slave overseer is an interesting one. Clark has always been described as a pretty harsh master to his slaves. We’ve already seen him give unruly Corpsmen lashes as punishment and shoot a man after “volunteering” him as bait for a river monster among other things. Those were people that he didn’t own and feel wholly “above”. So it’s safe to say that Clark probably doesn’t know about any part that York may or may not have had in the death of the man he sees in the fog, because if Clark did, York probably wouldn’t be around to be part of the Corps of Discovery. It may not play out anymore beyond this arc, but it’s an interesting thing to consider and also lets us know that there’s much more to York than what we’ve seen so far.