Welcome back to the Isu Codices. This month, we are looking into the English translation of the first volume of the Chinese manhua “Assassin’s Creed: Dynasty.”

The Tokyopop translation has numerous errors, but will be used for images and as much information as can be effectively gleaned.

So far, for a large portion of this installment, the actual Hidden Ones are background characters at best, with the primary focus seeming to be on the historical fiction angle up until near its conclusion.

New Concepts

Social Stealth

The second tenet of the eponymous Assassin’s Creed is the following: “Hide in plain sight.” In tracking down and killing targets, or even just looking around, Assassins, to a far lesser degree their predecessors the Hidden Ones, and occasionally their primary adversaries the Templars used the art of remaining inconspicuous in public environments to blend in with a crowd, often striking at the last moment and vanishing into the surrounding populace just as swiftly.

The art of social stealth, of blending in with crowds, has become less and less important in more recent games, particularly from Assassin’s Creed: Origins onward with a major change in gameplay dynamics. Consequently, while certain characters may use disguises or low-profile movement to disappear quickly, the overall effect is one of the pre-12th century Hidden Ones being rather loud and overt. Li E seems to be an exception, having been around in the 8th century but being able to hide amongst the people relatively easily, his taciturn nature likely helping a fair bit.

Of course, there are instances of that stealth not being followed in other releases taking place centuries later, from loud and violent tower sieges of Ottoman Assassin safehouses in the 16th century to the Jackdaw brig proudly showing a flag with the Assassin insignia high up as it roamed the mid-18th century Caribbean, but these violations are for a different discussion altogether.

And before anyone asks, no, we are not sure how wearing a hood around constantly in eras where hoods were not so common would equate to being beneath suspicion, especially in the 21st century, but it appears to work for these people, so it is hard to argue with the results.

Templar Schisms

In organizations as old as the Assassins and the Templars, it is hardly surprising that there would be drift in their methods over time, let alone conflict amongst the members over those changes. However, despite being a faction aligned with “order” at any cost, it is the Templars formerly known as the Order of the Ancients, that has far more internal conflict. Rather than bring up the actual outright assassination targets that one Templar or Order agent may have within their own organization (which could be its own subject) or those who elected to destroy their entire faction from the shadows using an Assassin or Hidden One agent, it seems more prudent to focus on the other prominent, wider-spanning revolutions.

The other example of an outright civil war within an organization tied to the Order of the Ancients would most likely be the French Revolution from 1789 to 1794 as orchestrated by outcast Templar François-Thomas Germain. Believing the Templars as corrupt after centuries of alliance with aristocracy, he set about (with some unknowing aid from Assassin Arno Dorian) removing high ranking Templars from power except his loyalists (those dead including Grand Master François de la Serre, who had been proposing peace with the Assassins at the time alongside Parisian Assassin leader Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau), completely changing the fabric of Templar society to rely more heavily on capitalism to more easily control the populace, thereby carrying out the “Great Work” of a new world order. Ultimately, even with Germain’s death in 1794, his mission proved a rousing success, as the alignment with overt aristocrats seemingly ended, instead resulting in more subversive means of establishing wider control without being too heavily in the spotlight.

Śarīra

These pearl-like, indestructible beads of a variety of colors are found among the ashes of cremated Buddhist masters. Long venerated as sacred relics by Buddhist monks, the Japanese scholar Abe no Nakamaro discovered that they were in reality remains of Isu and receptacles of their memories, not unlike several other artifacts such as the Memory Discs found by Altaïr ibn La-Ahad and Ezio Auditore da Firenze centuries after the aforementioned scholar. Among the first śarīra to be recovered by humans were those found among the ashes of Shakyamuni, a.k.a. Siddhārtha Gautama or the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, upon his cremation. His disciples collected them and sanctified them. Few knew of Shakyamuni’s true nature as one of the Isu or their direct descendants, at least according to Abe no Nakamaro.

Continued belowOver the centuries, more and more śarīra were accumulated as Buddhism rose in prominence in India. As the religion spread along the Silk Road into Central Asia, so followed scores of śarīra. They poured into China via the Western Regions during the Han dynasty, entering into the hands of the earliest Chinese Buddhist priests. These master monks resolutely protected the śarīra in their temples from the chaos and non-stop warfare that followed the collapse of the Han, passing this duty from generation to generation among their communities well into the Tang dynasty. It was under the cover of the 753 voyage back toward Japan with Japanese diplomat Fujiwara no Kiyokawa that Abe no Nakamaro, alongside the famous monk Jianzhen, attempted to return the śarīra to Japan to keep it away from the Golden Turtles.

History Lessons

Record of the Grand Historian by Sima Tan and Sima Qian

“A sweeping work of incredible scope, Sima Qian’s book covers more than two and a half thousand years of ancient Chinese history, beginning with the reign of the Yellow Emperor in 2696 BCE and concluding in the author’s own time in 87 BCE. Praised for his more objective approach to historiography, in which ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ were appraised with equal care, Sima Qian’s aim was to rise above mere biography and look for patterns and trends in the development of human culture.”

– The description of the Records in Assassin’s Creed: Revelations

Also known by its Chinese name Shiji, the Records of the Grand Historian is a monumental history of ancient China and the world finished around 94 BCE. Begun by Grand Astrologer Sima Tan (165 – 110 BCE) of the imperial court of Emperor Wu of Han, it was completed by his son, Western Han Dynasty official Sima Qian (circa 145 or 135 – circa 86 BCE).

The work, written in Classical Chinese, covers the world as it was then known to the Chinese as well as a period stretching from the legendary, deific Yellow Emperor to Emperor Wu of Han 2,500 years later. Through this work, Sima Qian is considered one of the creators of Imperial China after Confucius and Qin Shi Huang (see below), and due to the biographies in the work, he built the later interpretations of those two figures. The Records set the model for 24 subsequent dynastic histories of China, but in contrast to Western historical works.

The Records did not treat history as one narrative, but rather of smaller, overlapping units regarding famous leaders, individuals, and major topics of significance, split into 129 chapters and an autobiographical afterward by the historian himself. Here they are listed in brief, along with the number of installments in each section.

- Benji (Annals, 12): overview of important events, particularly those from the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE) to the then-present day. The Han Dynasty in particular had individual chapters for each of its five rulers (four emperors and one empress).

- Biao (Tables, 10): A genealogical table of the “Three Ages” from the Yellow Emperor’s time through to the Zhou dynasty, followed by nine more yearly or monthly tables featuring overviews of the reigns of the successive lords of the feudal states from the time of the Zhou dynasty till that of the early Han, along with the most important events of their reigns.

- Shu (Treatises, 8): Describing areas of state interest: rites, music, bells, calendars, astronomy, religious sacrificial ceremonies, rivers and canals, and “equalization” (the names of officials who had to buy crops in years of bountiful harvest and sell in years of crop failure).

- Shijia (Geneaologies, 30): Chronicling the events of the states from the time of the Zhou Dynasty until the early Han Dynasty and of eminent people (most notably Liu Fei, Xiao He, Cao Shen, Zhang Liang, and Chen Ping, each of whom had their own volumes).

- Liezhuan (Biographies, 70): Limited to the events that show the exemplary character of various important people, but often supplemented with legends. One biography can treat two or more people if they are considered to belong to the same type. The last biographies describe the relations between the Chinese and the neighboring peoples.

The most important of the chapters for our purposes is Chapter 86, listed within the Liezhuan section: “Biographies of Assassins.” Here, there are listed information regarding five assassins from different eras (all of whom are identified as capital A “Assassins” in the franchise, though perhaps better said as proto-Hidden Ones at best): Cao Mo (600s BCE), Zhuan Zhu (died 515 BCE), Yu Rang (died 453 BCE), Nie Zheng (died 397 BCE), and Jing Ke (died 227 BCE).

Continued belowQin Shi Huang (259 BCE – 210 BCE)

The sole emperor of the Qin dynasty of China (from 221 BCE until his death), also known as Zheng, King of Qin, this leader was the first emperor of a unified China. After having conquered all of the Warring States of China by age 38, he declared himself the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty, rather than continuing the pattern of calling himself “king” as had been the case in the preceding Shang and Zhou dynasties. While his own dynasty would end with his death, the pattern of calling the leader of China its “emperor” would continue for the next two millennia. Over the course of his reign, the lands of China were greatly expanded, including the Yue lands of Hunan and Guangdong and the Ordos Loop in Central Asia.

The First Emperor is known to have had quite an impact on Chinese history. Major political and economic reforms enacted with minister Li Si aimed to standardize the diverse practices of earlier Chinese states, while Qin Shi Huang is also infamous for the execution of scholars along with the banning and burning of many books. His public works projects were far more famous than perhaps even the man himself: various diverse state walls were unified into a single Great Wall of China and a massive national road system, and a city-sized mausoleum was constructed for him that was guarded by the life-size Terracotta Army.

He eventually died during his fourth tour of Eastern China, widely assumed to be due to poisoning from minerals such as mercury and arsenic in attempts at creating an alchemical elixir of immortality (a practice that continued to kill Chinese Emperors up until the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty in 1735 CE.

In the Assassin’s Creed franchise, between “Dynasty” and Assassin’s Creed II, we are shown that in that fictional continuity he was extremely paranoid of all assassins (possibly exacerbated by his repeated poisoning, along with the failed attempt by Jing Ke in 227 BCE [see above]), working with the Order of the Ancients to attempt to wipe them out and forcing the Chinese Brotherhood into hiding before being killed by Hidden One Wei Yu using a spear during his tour of Eastern China.

Jiedushi

The term “jiedushi” (节度使) was the title for regional military governors in China, translated as “military commissioner,” “legate,” or “regional commander,” as well as being the title of the post itself (the former will hereafter be referred to with lowercase letters, with the latter being capitalized, for clarity). These posts were authorized with the supervision of a defense command often encompassing several prefectures, the ability to maintain their own armies, collect taxes and promote and appoint subordinates. The practice was introduced in 711 under the Tang dynasty to counter external threats, and eventually abolished during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1376).

The most relevant of the jiedushi for this story is most likely An Lushan, promoted to the position in 742 by Emperor Xuanzong through the promotion of his Pinglu Army to being a military circuit. By the time of his rebellion, he held the position in Pinglu, Fanyang (in the northern part of modern Hebei) and Hedong (in the central area of modern Shanxi) with an army of 150,000.

The post An had been placed in charge of was the Fanyang Jiedushi (formerly known as the Youxhou Jiedushi before being given to An Lushan) that was created in 713 by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang as a buffer against the Kumo Xi and the Khitans. Following the An Lushan Rebellion, the district was renamed Youzhou Jiedushi, though the prominence of the resident Lulong Army and its association with the place led to it being better known as Lulong Jiedushi.

Li Bai (701 – 762)

Li Bai was Chinese poet during the Tang dynasty acclaimed from his own day to the present as a genius and a romantic figure who took traditional poetic forms to new heights, with over a thousand poems attributed to him. His skill is such that he is not only considered one of the most prominent figures during what became known as the “Golden age of Chinese poetry,” but his poetry was considered one of the “Three Wonders” alongside Pei Min’s swordplay and Zhang Xu’s calligraphy.

Continued belowHis life has even taken on a legendary aspect, including tales of drunkenness, chivalry, and the well-known fable that Li drowned when he reached from his boat to grasp the moon’s reflection in the river while drunk.

Much of Li’s life is reflected in his poetry: places which he visited, friends whom he saw off on journeys to distant locations perhaps never to meet again, his own dream-like imaginations embroidered with shamanic overtones, current events of which he had news, descriptions taken from nature in a timeless moment of poetry, and so on.

His early poetry took place in the context of a “golden age” of internal peace and prosperity in the Chinese empire of the Tang dynasty, under the reign of an emperor who actively promoted and participated in the arts, but it all changed with General An Lushan’s rebellion and the ensuing war and famine across northern China, with new tones and qualities that continued until his death, which itself occurred before these disorders were quelled.

Abe no Nakamaro (698 – 770)

Abe no Nakamaro (also known by his Chinese name Chao Heng) was a Japanese scholar and waka poet Japanese Nara period (710-794). He served on a Japanese envoy to Tang dynasty China.

In 717–718, he was part of the Japanese mission to Tang China (Kentōshi) on behalf of Empress Genshō, traveling as a student along with Kibi no Makibi, Awata no Mahito, and the monk Genbō. While the others returned to Japan, he did not, instead opting to take (and pass) the civil-service examination, becoming a Tang citizen. He did attempt to return to Japan in 734, but the ship to take him sank not long into the journey, forcing him to remain in China for several more years. He attempted again to return in 752, this time coming along on the return trip from the mission led by Fujiwara no Kiyokawa on behalf of Empress Kōken, but this one wrecked and ran aground off the coast of Annan (modern day northern Vietnam), leaving him stranded in Chinese territory along with his fellow former passenger, Kibi no Makibi, both of whom never returned to China. After that failure, he managed to return to the Tang capital Chang’an in 755.

With the onset of the An Lushan Rebellion later that year, it was unsafe to return to Japan, leading Nakamaro to abandon any hopes of returning to his homeland. Instead, he took several government offices, rising to the position of duhu (governor-protector, or protectorate governor) of Annan between 761 and 767, residing in Hanoi. He returned to Chang’an afterwards, and was planning his return to Japan when he died in 770 at age 72.

Abe no Nakamaro was a close friend of the Chinese poets Li Bai, Wang Wei, and Chu Guanxi, among others.

Yang Guozhong (Unknown – 756)

Guozhong was a Chinese Tang dynasty official serving as chancellor late in the reign of Emperor Xuanzong, a role he managed to attain by being noticed on account of being the second cousin of Xuanzong’s favorite concubine, Yang Yuhuan.

Though a gambler and a wastrel, Yang was keen with politics, being appointed chancellor by Emperor Xuanzong in 752 to succeed Li Linfu on account of Yang’s skill in managing finances. However, he proved to be disastrously incompetent as a chancellor, incurring the wrath of many in spite of remaining one of the Emperor’s most trusted officials.

Yang Guozhong’s conflict with fellow favorite official An Lushan eventually drove the latter into his rebellion, whereupon An formed the short-lived Yan dynasty in opposition to Tang. During said rebellion, Yang permitted An to capture the imperial capital of Chang’an through forcing General Geshu Han, who had been holding a favorable defensive position at the Tong Pass, to confront the rebel troops. As expected, the Tang forces were routed by the Yan armies under the command of Cui Qianjou.

During the attempt to flee the capital along with his second cousin and his Emperor, Yang, Consort Yang, and many of the Yang family were killed by the angry soldiers escorting Emperor Xuanzong because of the army attributing the chaos to them, and especially to Yang Guozhang himself.

Yang Guifei (719 – 756)

Continued below

Yang Yuhuan, often known as Yang Guifei (that designation being the highest rank of imperial consorts in her time) and briefly as the Taoist nun Taizhen, was the beloved consort of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang during his later years, and was known as one of the “Four Beauties of ancient China.” She was also the second cousin of Chancellor Yang Guozhong.

During the An Lushan Rebellion, as Emperor Xuanzong and his cortege were fleeing from the capital Chang’an toward Chengdu, the emperor’s guards demanded that he kill Yang Guifei due to blaming the rebellion on her cousin and their family. Though reluctant, the emperor capitulated and ordered his attendant Gao Lishi to strangle Yang to death before continuing onward.

Gao Lishi (684 – 762)

Gao Lishi, Duke of Qi, was a Chinese eunuch. A politician of the Tang dynasty and Wu Zetian’s Zhou dynasty, he became particularly powerful during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. He was often viewed as a positive example of eunuch participation in politics for his personal loyalty to Emperor Xuanzong, which withstood despite its putting himself in personal danger later, during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong’s son Emperor Suzong upon Emperor Xuanzong declaring himself Taishang Huang (retired emperor), when said loyalty drew jealousy from fellow eunuch Li Fuguo. As a result of said envy, Gao Lishi was exiled late in Emperor Suzong’s reign at Li Fuguo’s urging, until Lishi returned on account of a pardon in 762. Hearing of the deaths of Emperors Xuanzong and Suzong, he mourned the former bitterly, growing ill and dying that same year.

An Lushan (circa 703 – 757)

An Lushan was a general primarily known for instigating the eponymous An Lushan rebellion, as well as self-proclaimed Emperor of the roughly seven-year Yan dynasty.

An Lushan rose to military prominence defending the northeastern Tang frontier from the Khitans and other threats. He was summoned to Chang’an several times and managed to gain favor with both Chancellor Li Linfu and Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, allowing An Lushan to amass significant military power in northeast China. Following the death of Li Linfu, his rivalries with General Geshu Han and Chancellor Yang Guozhong created military tensions within the empire.

In 755, An Lushan, following 8 or 9 years of preparation, instigated the An Lushan Rebellion, proclaiming himself the ruler of the new Yan dynasty.

The An Lushan Rebellion spanned from 16 December 755 to 17 February 763. This rebellion involved the death of some 13–36 million people, making it one of the deadliest wars in history.

However, An Lushan himself was assassinated by the eunuch Li Zhu’er in 757 as part of a plot orchestrated by members of the An household including his son An Qingxu, who he was going to pass over for the crown in favor of another and therefore feared for his life given An Lushan’s increasing instability. He was posthumously insulted by being given the burial of a prince rather than an emperor, and being given the unflattering posthumous name “La,” meaning “unthinking.”

Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685 – 762)

Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, also commonly known as Emperor Ming of Tang or Illustrious August (personal name Li Longji) was the seventh emperor of the Tang dynasty in China.

He was credited with bringing Tang China to a pinnacle of culture and power. A diligent and astute ruler during the early half of his reign with capable chancellors like Yao Chong, Song Jing, and Zhang Yue, Emperor Xuanzong is nonetheless infamous for his overly trusting nature toward the wrong people in his late reign as well, such as Li Linfu, Yang Guozhong, and An Lushan. As a result of his trust, the Tang golden age ended in the An Lushan Rebellion, which led to his death as well.

Emperor Xuanzong’s 43-year reign being the longest of the Tang emperors, with him retiring from the throne in 756, during the An Lushan rebellion after fleeing the city of Chang’an, once the news of the ascension of his son Li Zheng as Emperor Suzong reached him.

Yan Jiming (730 – 756)

Continued below

The son of Yan Gaoqing, an official who was himself the cousin of Yan Zhenqing, the latter two of whom are better known.

Yan Jiming is mostly known for being captured by An Lushan in the siege of Changshan. When his father refused to surrender, Jiming was beheaded as punishment.

Jianzhen (688-763)

Jianzhen, or Ganjin in Japanese, was a Chinese monk who helped to propagate Buddhism in Japan. In the eleven years from 743 to 754, Jianzhen attempted to visit Japan some six times. Ganjin finally came to Japan in the year 753 and founded Tōshōdai-ji in Nara. When he finally succeeded on his sixth attempt, he had lost his eyesight as a result of an infection acquired during his journey. Jianzhen’s life story and voyage are described in the scroll, “The Sea Journey to the East of a Great Bonze from the Tang Dynasty.”

New Issues

Assassin’s Creed: Dynasty – The Flower Banquet (Chapters 1-7)

This volume features no modern-day portions, presenting itself entirely within the past. There are some elements brought up in a letter after the final chapter of this volume, but they are instead addressed in sections above.

Chang’an, China

Spring 754 CE

Li Bai, already drunk, found himself drinking wine on a balcony. In his intoxication, the poet rambled about his life and the day’s affairs to a solitary young stranger beside him, with his first subject being the annual contest known as the Flower Banquet that was to commence soon. According to Li Bai, the Flower Banquet, aside from being about the procession with the most splendor (for which the winning team would win prizes), also meant, aside from being the best time of year to enjoy flowers in the city, but also the only tome in the year when the city itself is open to commoners.

However, to the poet’s disillusionment and experience as a former scholar within the court, there was nothing good to see within the palace walls, and he hated it all from his prior work as an imperial scribe (from which he had intentionally allowed himself to be dismissed). From rigged contest in favor of Right Chancellor Yang Guozhong to the praise poured on the chancellor’s cousin Yang Guifei, the only reason Li Bai even considered returning briefly to Chang’an was to attend the funeral of the late Abe no Nakamaro, who had died in a shipwreck while trying to return to his native home of Japan. Beyond that, Li Bai believed this trip would likely be the last time he saw the city itself, whereas he would likely go back to roaming and drinking away his sorrows.

Only when the poet, toward the end of his venting, suggested to the silent stranger that they take in the scenery of the city brimming with peonies (a type of pink flower) did the man finally respond: “One peony is worth a thousand gold, one peony can buy the favor of officials. And how many people have had their families destroyed for the sake of one peony?” Li Bai recognized the tone, that of the same kinds of individuals he had once known as a boy: one of the Hidden Ones (better known by their latter day name as Assassins). While the secret community to which he had bonded apparently did not exist any longer (seemingly a lower time for the Chinese Brotherhood), this Hidden One would continue to fight for those who suffered from injustice and oppression even in the clamorous splendor and prosperity of the Tang Dynasty.

The stranger, hereafter known by his name Li E, was only there to “pick flowers,” leaving soon after saying so when Li Bai misconstrued him to mean flirting or finding love. On the streets below, Li E set about dispatching three men around the Shifting Spring Cage, centerpiece of Yang Guozhong’s entry to that year’s Flower Banquet, hiding them amongst the flowers themselves. As revealed while interrogating the last of the henchmen, Li E sought vengeance for the violent robbery of Duling village’s prized peonies, the owners of which had apparently been killed in the process. While he found out that their employer was in the palace itself, he also did not spare the last guard, merely taking a bloodied peony as he departed.

Continued belowLi E entered through the palace gate in time to see the procession for the famous General An Lushan, Jiedushi of the regions of Fanyang, Pinglu, and Hedong. The general, reputed as a “battle god of legend” with “fiendish” guardsmen, had various rumors about him, from notes of his steadfast defense of the northern borders of the kingdom to assumptions that he may have been plotting treason, but his arrival when called by the Emperor seemed to indicate the latter was false.

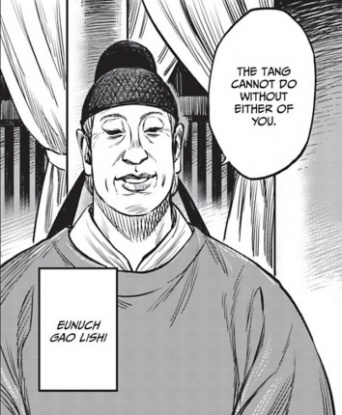

Whatever the reason, the evening after the winner was declared as Guozhong (as predicted despite missing a wagon), An Lushan entered the audience chamber, to Emperor Xuanzong’s pleasant surprise and Lushan’s rival Yang Guozhong’s chagrin. Despite seemingly deliberately ignoring court protocol in not kneeling to the Emperor, Lushan instead bowed to Yang Guifei (the “mother”) then Emperor Xuanzong (the “father”), in accordance with the customs of his Hu clan, which the emperor and the consort saw as an amusing joke. There were verbal barbs thrown from Guozhong to Lushan and back, but eunuch Gao Lishi (the very same one who had been incensed by Li Bai to the point of having him removed from the court) tried to mediate between them (with Emperor Xuanzong’s clear favoritism for An Lushan not helping in the slightest). Either oblivious to his Right Chancellor’s irritation or ignoring it, the Emperor catered to his guest by playing a song on a drum that he invited the half-Sogdian (an Iranian civilization), half-Göktürk (or “Blue Turk”) general to dance to with one of his native dances, which quietly enraged Guozhong.

Guozhong’s delegates and guards were little more than a gang of hired thugs by their “Master Yang,” and their leader did not appear to be Guozhong himself, but rather a one-eyed petty crime boss. The delegates had been promised whatever they asked for in exchange for having won, with rewards for prior envoys ranging from riches to property to official positions in government. However, it all would depend on what mood the capricious Yang Guozhong was in when meeting with them again. That said, they were to wait outside in the nearby Chenxiang Pavilion, where they saw Li E waiting, still holding his bloodied peony and noting he was there to “claim lives.” Over the course of the very loud song inside, Li E killed every member of the gang present with just a knife and his hands and feet, compared to them not having decent weaponry so as to enter the palace in the first place.

After the dance, Lushan was showered with praise by the Emperor, along with given even higher authority (as “Governor of the Stables”) and rank increases to his men both alive and dead. Guozhong of course hated all of this, but those promotions required his personal approval, which gave Guozhong a degree of satisfaction and Lushan one of rage as the latter was sent away.

As noted in a flashback for Li E, the lengthier words of the Creed seem different for this Hidden One. They are as follows: “We are the guardians of the poor. We fight for the freedom of ideals. We give ourselves up entirely for this, without fear of shedding blood. Without fear of death. We work in the dark to serve the light. We do not serve the powerful.” The overall effect is similar to the Italian Brotherhood, but the words differ slightly. It is unclear if this is the wording used by all Chinese Hidden Ones, or if it was taught to Li E by his teacher from Central Asia.

Following the deaths of the gang members, a search was sent out, but Li E was nowhere to be found by the palace guards, having escaped into a passing cart driven by a stranger who did notice him land in the hay. The stranger, identified as Yan Jiming with the cart driven by “Uncle Chen,” helped to hide Li E from those searching, earning his gratitude and, aside from that, his name (the first time it was stated on panel at all) before the Hidden One departed by rooftop, seen by Li Bai once more, who apparently penned his “Ode to Gallantry” after Li E himself in tearful joy.

Continued belowAlone with Gao Lishi once more, An Lushan declared his true intent: he wished to be the leader of the “Golden Turtles,” evidently the Templar faction in China at that point in time, and believed Yang Guozhong to want him dead despite the general’s favoritism from the Emperor. Gao Lishi was another member, but the leader was Yang Guozhong, as, due to a bit of circular logic over time, not only could only a Golden Turtle leader be the Right Chancellor, but due to the position having been intertwined for an extended period, only the Right Chancellor could be the leader of the Golden Turtles. Given that Lushan was illiterate, Guozhong believed him to be ill suited to be an official despite his military might, a situation of which Lushan was well aware.

Rather than wait to be recommended, Lushan elected to “start his own Golden Turtles,” declaring that the next time he entered the capital, only one person between he and Guozhong would live by the end of his stay, with Gao Lishi needing to pick one side or the other. He claimed he was not proposing rebellion, but rather acting in the best interest of Tang to execute Guozhong and “cleanse the state.”

We will check back next month, by which time the second volume of this story is set to release in an English translation!