Welcome to Postal Notes, a critical read through of the series “Postal.” This series of columns will be done in a mixture of essays and observations of various lengths. I will be using the seven core trade paperbacks that collect issues #1-25 and the various one shots for a total of 27 issues overall. In this column we’ll be working through the fifth trade, issues #17-20. The first four issues of “Postal” are on Comixology Unlimited.

Mirror, Mirror

I’m not sure how much of this is conscious, but the fifth volume of “Postal” has this pronounced recurring motif of the mirror in both its art and structure. Visually Isaac Goodhart uses the motif by creating mirrored or symmetrical imagery, which makes for balanced or tense pages and scenes. Writer Bryan Hill, structurally has a habit of playing the same scene twice with different characters or echoing a scene from an earlier issue. Through the use of the mirror the “Postal” creative team create a sense of cohesion and duality in these four issues as they deal in plots that are set in different moments in time as well as help to propel it to the climactic sixth volume.

“Postal” volume 5 begins with a call back to an earlier scene as formerly special agent Bremble enters Isaac’s compound, a derelict school. The location echoes the location we see Bremble racing through back in Afghanistan in issue #11. K. Michael Russell ties the two spaces together with the use of a brown color palette and, less stylized, natural lighting. Visually, due to more space Goodhart’s paneling does not directly reference the earlier scene even if it ends the same, with Bremble shocked to once again find children! And a woman with a shotgun full of rock salt trained on him.

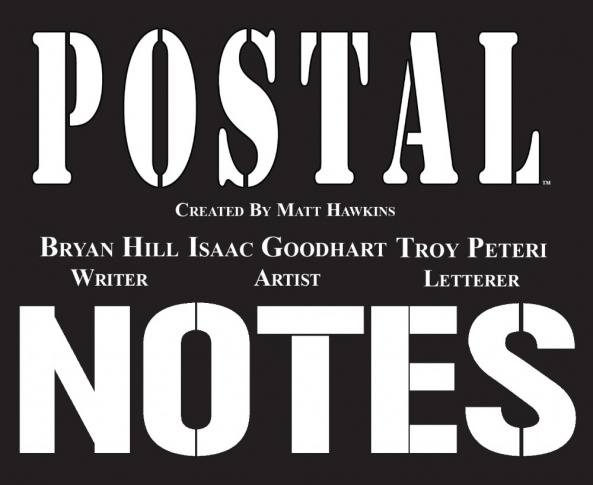

The mirror as a visual element becomes more pronounced in the next scene as Mark visits Molly Schultz again. With the exception of the establishing shot of the mine entrance, the remaining 5 panels all mirror or balance one another through symmetric paneling. Goodhart makes good use of perspective in this sequence as he maximizes the minimalist environment, the cage that holds Molly Schultz, to create these mirrored and symmetrical images and paneled sequences. The changing perspectivs confuse who it is that is behind bars as Mark deals with his subconscious yearning for more freedom as he struggles to articulate it. Goodhart uses the cage isn’t to dissimilar to what director Billy Wilder and cinematographer John Seitz do with shadows at the start of Double Indemnity. K. Michael Russel colors the scene in a near duotone manner (the light emanating from the lamp has some white in it) that further ties Mark and Molly together as kindred spirits of a sort.

Mark’s conversation with his Mother, where she voluntells him to be Mayor, is an extension of this visual design with some complications. The earlier sequence used Russel’s colors to link the two characters together through space and color. As Laura talks at her son, Goodhart uses page design and some dropped backgrounds to create the sense of tension in the moment and show how they harmoniously balance one another. As the conversation, for want of a better word, really gets going Goodhart drops turns them into talking heads and asymmetrically balance them off one another as well as drop the background for Russel to fill in with a light gradient of solid complementary colors. Laura is backed by a warm orange while Mark is supported by a cooler blue. Russel’s coloring establishes the tension in the moment, as Laura says “I want you to be Mayor.” While the art team also visually shows how the two opposite personalities can harmoniously support one another as they form a rough yin-yang symbol. On the second page mirrors are established through the use of latticed paneling and counter active shifts in perspective between Mark and Laura’s paneling. Through Laura’s three panels the perspective becomes a tighter and tighter close up while Mark’s eventually pulls away.

It isn’t quite a match cut, but the transition from Bremble’s screaming face at the sight of the decaying head into a scene of a man begging for his life before his head is blown off is similarly effective.

Continued belowThe motif begins to come through more in the writing with issue #18 as Hill repeats the same basic interrogation scene, what does a person desire, between the coupling of Brembel and Eva and Mark and Maggie. Held captive by Isaac, Bremble is questioned by Eva on what it is he wants out of all this. Why does he care about Isaac and Eden, WY so much. While the basic staging of the scene of Bremble on the ground and Eva standing upright creates for obvious moments mirrored imagery Goodhart’s layouts don’t really emphasize it the same way it was in prior sequences. Bremble again choses to live in his own private hell than tell Eva what it is he really wants.

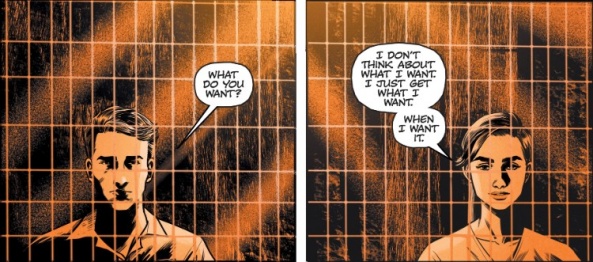

Meanwhile, in Eden and the companion to this scene Mark and Maggie have a similar conversation that goes in the opposite direction. This scene features more explicit mirrored and symmetrical paneling as well as Russel again employing a duotone palette of purple and orange/pink. Unlike Bremble, when Maggie is asked what is she wants, she explodes! Angry at Mark for perceived distance and visitations with Molly. Mark plays the Eva role, the calm and collected one who is permitted to stand.

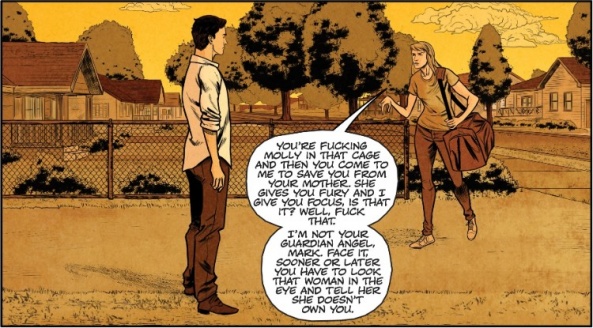

Later on in the collection, there is another echo of a scene from an earlier comics as the anonymous populous of Eden take a stand against Mark’s mayorship. It echoes events from the first collection when Mark is beaten by not-so-anonymous residents of Eden under the thrall of his father. Those residents thought they were anonymous to Mark, the same goes for this new lot, both are wrong. Unlike the scene at the start of the collection that figures Bremble as constantly running from his desires and eventually always finding himself back in the same space, this sequence is an example of how Mark has grown over the previous four collections. Mark doesn’t leave this group of people to be murdered by his Mother in retaliation, eventually earning a reprieve for them. He lies to her about Maggie’s involvement. This sequence shows how independent Mark really is of his Mother, he just also liked the previous status quo of not being Mayor.

The use of the mirror and visually organizing the book around symmetry has a pleasing effect. Visually it creates for plenty of balanced images that years of Western Art History tell me is innately pleasant. The real strength comes from how Hill expresses it through his writing and structure. “Postal” volume 5 breaks one of the storytelling traditions of the series, presenting things in a mostly linear fashion. What brief breaks in linearity we have had are from dream sequences. The Bremble plot takes place three months in the past compared to the present day Eden thread. Previous Bremble threads have been disconnected or more expository in function, hinting at the character while the history of Eden is revealed. By mirroring his experience at points with the main events in Eden, Hill and the creative team are able to create a cohesive narrative that cuts across time and propels things to their final confrontation in “Postal” volume 6.

Meet the Father

After haunting the pages and psyches of the cast in “Postal” for 18 issues, we finally get the return of Isaac Schiffron. He looks a bit different from the last time. I’ve yet to find a reason “why,” both from the creative team or within the book, for this drastic change in apperance. There are a few reasons you could infer. Mainly that when we’ve previously seen Isaac, we haven’t really seen him. In the third issue, where his followers beat Mark, he looks like a Mountain of man. That sense of enormity is created by Goodhart through the use of low angle perspective with Mark in the foreground for scale. That perspective mixed with the dramatic spot lighting behind him makes appear to be the devilish dragon Laura spoke of. When we see him again in the Laura centric flashback from issue #6, similar techniques are employed and that whole sequence needs to be understood through dream logic. So we haven’t actually seen him in the flesh, at least well.

Until this point the depiction of Issac Schiffron is much like the Spirit’s archnemesis, The Octapus, a figure readers only understood through the characters purple gloves. In the world of soap opera television the mad, exiled, patriarch of the Schiffron clan is treated similar too Alistair Crane, the chief villain of Passions. These examples follow the simple maxim that the monster is more freighting and powerful when it is veiled. That way everything can be attributed to them and their monstrousness only grows in the minds of the terrorized and reader.

Continued belowThe shift in character model is a good one that better fits the style and mood of “Postal.” There is a kind of generic evil to his previous model, figured as literally the big bad man. It is more effective to figure him as Moses like, old with a great beard and staff that isn’t far off from Charlton Heston – though there are a few panels that look a little like Liam Neeson Zeus. That fits the series overall use of Christian symbolism and immediately explains his character on a visual level. He is like Moses come down from the Mount Sinai angry that his followers have disobeyed him and now plans to go Old Testament on them.

Goodhart finds a lot of expressive potential in this character design. It isn’t that other figures are stiff, but there is a sense of devilish energy and charisma in his body language compared to the other cast members. As he meets with Bremble for the first time and sits on his throne, his posture and the way the light catches his wrinkles is visually interesting compared to the smoothness of Bremble’s body. That sense of charisma reveals the performative aspect at the heart of his character. He is clearly playing a part when he meets with Bremble, but his nine panel grid confessional to his new family is where it comes through the most. Over the course of the nine panels we see a wide range of emotions and signs of slippage as his zen like philosophizing slowly dissolves to brutish, misogynist, anger at his wife and son.

The change in appearance is a bit jarring, but an overall effective one that also may signal the means Laura and Mark can defeat him in the coming battle.

What’s Eating Mark Shiffron; Or an Experience that will make a Therapist Lots and Lots of Money

Whatever gemotric shape you make out of the Mark and Laura, Maggie, Molly Madonna-Whore complex (again for want of a better term) comes to a head in this collection. To a degree this is the collection where the 4 issue a collection format feels the most limiting, an extra 10 pages to explore this shape and 10 for Mark as Mayor do not sound like immediately poor ideas. That said writer Bryan Hill makes good use of the page real estate he does have, building a drama through absence. Where the scenes that we are shown (Mark spending time with Molly) supposes that something isn’t happening (Mark spending time with Maggie.) Mark and Maggie do not have a scene together until about half way through this collection which is surprising given their triumphant kiss moment in the previous collection, which adds fuel to Maggie’s anger in that first scene together.

At the same time other long term storytelling choices Hill has made, primarily reducing the amount of internal monologue from Mark, help to add to this dramatic fire. By this point the reader should be feeling rather ambivalent about Mark’s nature. He’s shown an increasingly tactical brutality to the various problems Eden faces. The one bit of internal monologue we get this collection is when he notes how his Mother is afraid of him, and he likes it. Goodhart has shown a real skill in making Mark emotive in non-traditional ways, but in this collection the character reads and looks like a blank slate a fair amount of the time (in a good way.)

These storytelling choices make for their final confrontation to be legitimately suspenseful. Not in the Hitchcock idea of suspense, but in the sheer unreliability of it all. Molly has Laura with a knife to her throat, Maggie has a gun trained on both of them and Mark finally has to make a choice. After an establishing panel, the use of close ups and paneling-as-editing places the sequence in the same visual language as the stand off at the end of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly which further activates a feeling of tension. Mark takes advantage of the moment to win back his position as Post Master and reprieves for the anonymous residents of Eden, standing up to his Mother in the process. In the end he makes his choice, Maggie, and Molly is vanquished.

Continued belowI lack both the space and strong theoretical grounding to really open up on this, but that whole sequence is incredibly Freudian, sexually charged, and filled with phallic imagery as it all comes. After Molly’s initial beating she mentions to Laura about how she “fucked me … then your son fucked me. Now I’m gonna fuck you.” As she lords over her with a large chef knife. Meanwhile you have Maggie and her gun, acting an extension of Mark, which seems to be accessing the symbolic phallus in some ways.

More interesting is what comes after. Goodhart and Hill subvert the normal representative gender dynamics by showing Mark to be the feminized character in the aftermatch. I mean feminized in the general academic sense, not in the way his Father views his son as a failure and un-manly. If Maggie and the phallic nature of the gun wasn’t evident before this panel pictured below makes it abundantly clear. After some love making Maggie is the one drawn with the cigarette, another classic phallic symbol an old Hollywood code for sex, which further masculinize her. Mark is the one shown to be emotionally and physically vulnerable throughout these situations. By subverting these normal depictions the creative team both reinforce/restate what is that makes Mark and Maggie wok as a couple: they support each other; as well as visually counter Isaac (and Laura’s) presumptions about their son as weak or failure. He is successful, achieved his goals and got what he desired in the end, which is better than what his parents have.

K. Michael Russel Process Video: “Postal” #20 Cover

K. Michael Russel goes through his process on coloring the cover for “Postal” #20/cover for this volume.