To fully appreciate the importance of the small press, it’s vital to understand how they’ve been impacting mainstream books. It’s difficult to track down certain specifics due to the low key nature of self published books, but this segment of Small Press Month is an effort to provide a framework for put the rest of the series in perspective. If you find yourself interested but not fully satisfied by this synopsis, there are several full length books which have been written on the subject.

If you look at the early years of the comic industry, it’ hard to pin down a definition of small press comics. In the late thirties and forties, all of the publishers were relatively new, all of them had limited numbers of titles, and for the most part all of them were pretty successful. This was, after all, the so-called ‘platinum age’ of comics with million-copy print runs being standard.

The first comics that might meet modern criteria for small press were known as Tijuana Bibles. They were mini-comics usually based on well-known newspaper strips or celebrities, usually eight pages or so in length, and pornographic in nature. Tijuana Bibles were most common from the 1920s to the 1940s, and their popularity at the time was due in no small part to their content. It’s hard to imagine in the age of the internet, but at that time possession of pornography of any kind was illegal in the United States. The illicit nature of the books explains why nearly all of them were made anonymously, and is also the source of their name – no red blooded American would print such a thing, so they must be smuggled in from some seedy border town.

Tijuana Bibles slowly faded away, and through the fifties there wasn’t much action in the small press arena. There’s no obvious explanation for this, but there are a few factors which probably account for the lull. This was still a decade or more before the first comic shop would open, so there was no direct market for self-published books. There was a much wider variety of comics available at newsstands, so there no untapped niche to target. Comic fandom was still in its infancy, and there were no dedicated trade magazines or fanzines for advertising. If a creator did take a new book to print, there were two main methods to sell it: mass distribution, or hand selling. The former would have the appearance of being a larger publisher, and the latter would pretty much guarantee obscurity.

One important event that did happen in the fifties was the publication of Dr Fredric Wertham’s “Seduction of the Innocent.” This book led to, among other things, senate hearings on the dangers of comic books, the eventual closing of horror publisher EC Comics, and the reduction of the comic industry to superheroes. The creation of the Comic Code created a void in available content, and former fans of the purged genres decided to fill it themselves.

It may have been coincidence, but this rebellion against censorship in comics happened to come during the broader counterculture movement of the sixties. Young creators competed against each other to see who could make the most obscene work simply because they weren’t supposed to. These ‘forbidden’ comics appealed to hippies, especially hippies who grew up reading code-approved books. The source of demand for these small press books also provided an outlet for distribution – stores specializing in hippie paraphernalia (head shops) were cropping up across the nation and were more than happy to peddle these underground comix.

With the background established, let’s zoom in on some of the important creators and works.

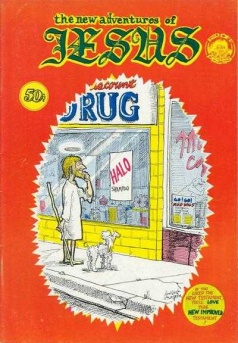

One of the earliest, if not the earliest, underground comic books was created by a Texan college student named Frank Stack. In 1961, he began writing and drawing a comic strip featuring Jesus Christ. They were too blasphemous for publication in that time and place, but he did share them with friends under the pseudonym Foolbert Sturgeon. One of those friends was Gilbert Shelton, who liked them enough to save. A year later, when he had a decent amount (a dozen, according to Comix Joint), Shelton photocopied the strips and he collected them into about 40 stapled booklets he distributed to friends as “The Adventures of Jesus.” Some people consider this the first underground comic, but didn’t really make an impact until it was reprinted by Rip Off Press seven years later.

Continued belowThe first real splash in underground comics was made by Robert Crumb. He had previously had some strips printed in ”Help!” magazine (similar to “Mad” magazine, both were from Harvey Kurtzman) and in the underground New York newspaper ”The East Village Other”, but his big breakthrough came when he wrote and drew “Zap Comix” as tributes to the pre-code comics he had enjoyed as a kid. The first issue was printed in February 1968 with the help of Charles Plymell and Don Donahue at Apex Novelties. The exact size of the print run is disputed, but it was somewhere between 1,500 and 5,000 copies. Some were sold by hand by Crumb, his wife, and a couple friends around their home in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. The rest were sold through Third World Distribution. The first issue was printed in February 1968.

Today, depending on where you look, you may see someone say the spelling of comix was done to emphasize the X-Rated content. This seems very unlikely for several reasons. First, the MPAA rating system originated around the same time as “Zap Comix,” and the initial meaning of X was essentially today’s NC-17 rating – people under age 17 should not see the film, even with an adult. The rating system wasn’t trademarked, and the pornography industry didn’t co-opt the X rating until the mid 70s, well after “Zap Comix” debuted. Later undergrounds also used the modified spelling even when the content wasn’t particularly subversive. More to the point, if printers or publishers actually believed parents might interpret the X in comix to mean adult content, would Marvel ever have printed “X-Men”?

The altered spelling seems better explained by the counterculture nature of the book and the youth of its creator. Every generation experiments with an altered lingo that’s impenetrable or nonsensical to adults. More recent examples would include the phonetic spelling of the early 90s (gawd, kewl), 1337 speak, and instant messenger abbreviations (tl;dr lol).

Beginning with issue two, Crumb turned the book into an anthology and began inviting some cartoonist friends to share in the fun. One was Gilbert Shelton, the Texan mentioned earlier. Two others were Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso, who were well known for making concert posters. Moscoso helped arrange a deal with the Print Mint, a printer and distribution company. With the enhanced resources, the third issue of “Zap Comix” had a print run as high as 50,000. It became so popular so quickly, it actually suffered some brand weakness – the term Zap Comix was later used interchangeably with underground comics instead of referring specifically to Crumb’s book.

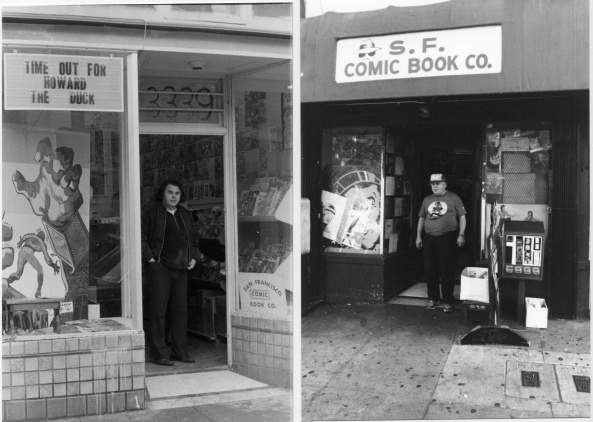

After Crumb proved both that demand existed and that success was possible, new underground books appeared with surprising suddenness. Many of them came from Crumb’s hometown, which was coincidentally where The San Francisco Comic Book Company, the world’s first comic shop, was opened by Gary Arlington. He had been a serious collector of EC Comics and their back issues were a major cornerstone to his business. Arlington’s store became a hub for underground cartoonists and he played a significant behind-the-scenes role in the development of both titles and talent. As one example, he noticed Richard Corben’s work in a fanzine and hired him for his first professional comic work. Arlington also helped Berkeley University and Ron Turner, the founder of publisher Last Gasp connect with creators for a comic to promote the first Earth Day in 1970.

Last Gasp quickly made a name for itself when it printed two issues of “Air Pirate Funnies” in 1971. The books were created by Dan O’Neill with input from Shary Flenniken, Gary Hallgren, Bobby London, and Ted Richards. They featured Disney characters like Mickey Mouse in some very un-Disney situations, and were intended to provoke a lawsuit. When Disney didn’t immediately oblige, O’Neill reportedly had some copies of the book smuggled into a meeting of the Disney board of directors by one of the directors’ sons. (Note: the first issue was published in July 1971, and the lawsuit was filed in October the same year. O’Neill was obviously very impatient to be sued.) After a nine year court battle and being out a net 2.19 million dollars, Disney settled the case in exchange for O’Neill not printing any more issues. (The full story is rather entertaining, but far outside the scope of this article. I highly suggest reading the above link for more details.)

Continued below

Another San Francisco publisher, Rip Off Press, was started in 1969. One of the four founders was Gilbert Shelton, who’s been mentioned twice above. He and three other friends (Jack Jackson, Fred Todd and Dave Moriaty, all Texans) began by reprinting some of their previous work for new audiences, including Jackson’s “God Nose” (originally 1964) and Frank Stack’s “New Adventures of Jesus.” Over the next few years, they expanded into new content and had many horror titles do well. They also printed a large number of books from Crumb.

Meanwhile, a 23 year old in Wisconsin named Denis Kitchen had heard of “Zap Comix,” but was unable to find a copy. So, the intrepid young man decided to create his own. At first, Kitchen had them printed locally and distributed them on consignment by hand to any head shop or other outlet who would take them. After a bad experience with the Print Mint and successfully selling through a 4000 copy print run of “Mom’s Homemade Comics,” he founded Kitchen Sink Press in 1970. Kitchen Sink partnered with Last Gasp and Rip Off to distribute each others’ titles, resulting in average sales of 10,000 copies for each issue. According to Kitchen, the cartoonists at the time were very aware of the cultural impact they were having.

Unfortunately, the runaway good fortune of the underground comic market wouldn’t last. After just a few years, things began to deteriorate fast. In 1973, two events hit it hard from opposite sides.

First, the broader counterculture/hippie movement was beginning to fade out. There was less traffic in head shops generally, and less demand for comix specifically. This problem was compounded by two other factors. The buyers for the head shops had never dove into comix in any meaningful way and treated them as interchangeable without bothering to rotate stock (Most comix were sold on a non-returnable basis). They ordered when their rack got low, but as the poor quality books piled up, the racks always seemed to be empty. Also, the appeal of comix had always been limited. Most comix readers were former comic readers, but there wasn’t much cross-pollination between comix the current mainstream readers. As such, the budding direct market had little interest in picking up the slack from the declining head shops.

Second, a trial centered on “Zap Comix” #4 that began in 1969 finally reached a conclusion. Almost as soon as “Zap” began appearing on store shelves, it was seen as a violation of obscenity laws and arrests and confiscations followed. Nearly all of them turned out to be nothing but a hassle for the people involved, but there was one case that started in New York and went all the way to the Supreme Court. After selling copies of “Zap” #4 to a policeman, four people were arrested. Charges were dropped against two of them, and a third was let go as a case of mistaken identity (the employee who was arrested wasn’t at work the day of the sale). The fourth was Peter Kirkpatrick, and was found guilty. He appealed, but lost repeatedly until the Supreme Court established the Community Standard doctrine which allowed communities to determine their own obscenity laws. During the case, and especially afterward, everyone from printers to retailers became more cautious about what books they would offer, resulting in fewer sales of underground comix.

Perhaps the last nail in the underground comix coffin came when Stan Lee reached out to Denis Kitchen about producing one for Marvel Comics, because nothing kills a cultural movement faster than being embraced by corporations. Lee was looking to print something as edgy as the underground comix, but softened for more mainstream audiences. Kitchen accepted and recruited several comix cartoonists to participate, but the final product was still too edgy to be officially printed by Marvel, so it was released by a subsidiary of their parent company to avoid controversy. Titled “Comix Book,” it sold poorly and Marvel canceled the book after issue three. The fourth and fifth issue had already been assembled, and Kitchen was later allowed to publish these through Kitchen Sink Press. (In 2014, Dark Horse released a nice hard cover collecting the best of this series.)

Continued below“Comix Book” was a watershed moment for the industry, however. Before many of the cartoonists would agree to participate, Marvel had to acquiesce to some of their demands. For instance, the creators retained copyright to the material, and the original art was returned to them. While there was no immediate impact from this, it was noticed by the regular Marvel talent and started some very important conversations.

Underground comix aren’t dead, of course. Many of them never had regular release schedules, and are still officially being published. “Zap Comix” #15, for example, was published in 2005. Still, it’s hard to deny they were a product of a time gone by. Many of the cartoonists from that era freely admit it was low brow art, created when they were young. Nevertheless, underground comix played a vital role in restoring some diversity to comics at a time when there was none. Even more importantly though, are the contributions those same cartoonists made to the industry after they matured and stopped drawing penises bursting through city streets.

Nowadays, we call those Alternative Comics. I’ll tell you all about those next week.