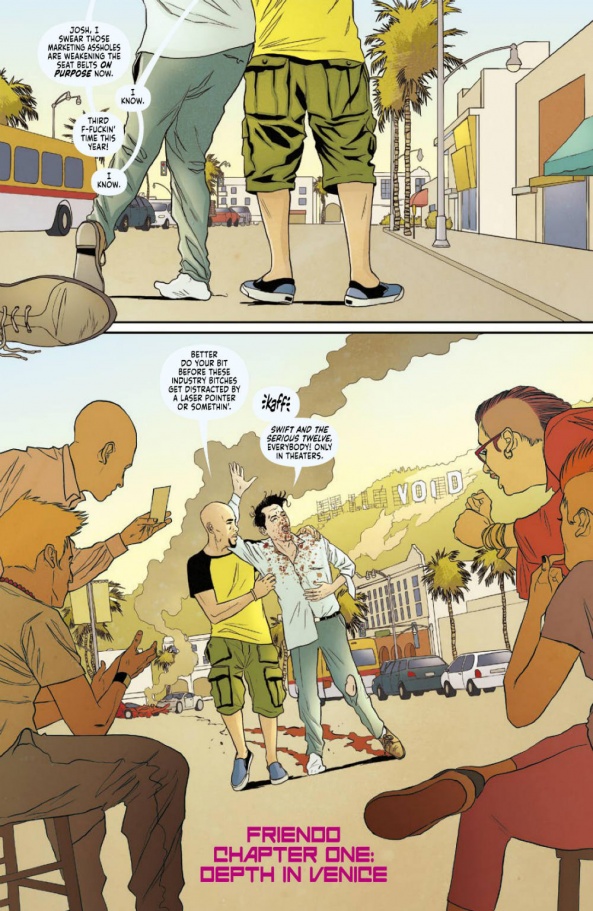

A dystopian Los Angeles ravaged by rampant consumerism and advertising AI’s is the world of “Friendo,” a new series from Vault Comics. I had the opportunity to sit down with “Friendo” writer Alex Paknadel and artist Martin Simmonds to talk about the design and collaboration of the series, the influence of religious fundamentalism represented in Leo, the main character, as well as other influences in the book. I talked to them both separately, so you’ll find Martin’s interview first, then Alex’s. We also have preview pages, including some exclusive ones, for the first issue which hits stands September 26th. Be advised that some of the preview pages are NSFW.

Martin thanks for taking the time to talk to me. To start with, what is “Friendo” about to you?

Martin Simmonds: It’s a pleasure to chat with you! I guess I see “Friendo” as a what if…? scenario. I think it’s fair to say that the real world’s gone down the pan recently, and if we continue on this path, where would it takes us? So “Friendo” is a disturbing take on where we could end up. It’s a very bleak story in many respects, and suffice to say the story takes us down some pretty dark avenues. It’s part dystopian sci-fi, part dysfunctional buddy story, and part violent adventure into consumerism.

You and Alex’s new book, tackles a lot of different ideas. Religious fundamentalism versus the “real world,” technology and consumption, capitalism and consumerism, and probably more that I’m missing. As an artist, where do you look to begin to craft visuals to convey such philosophical and literary themes?

MS: I’m from a graphic design background, so I came at it from that angle. I looked into a lot of corporate identity design. I’m often left feeling a bit cold by the slick, minimalist design you see everywhere, as a lot of corporate design seems to stem from the Apple corporate identity. The thing is, it’s either not executed as well, a rip-off, or just not that individual. Don’t get me wrong, it often does look great, but equally it can become homogenized. Having said that, it’s something I wanted to explore with the design and some aspects of the interior artwork. Particularly in the logo design, I wanted to get that slick corporate ID across, my starting point being Bauhaus-meets-Apple corporate identity, something utilitarian and corporate.

Infographics played a big part as well, the kind of simple instructional illustrations you see every day in everything from the flat pack coffee table you brought, through to the instructions you see on the safety cards on a plane. And it’s that simplicity which influenced the minimalist approach to some of the artwork.

There’s a lot of references in this first issue to The Wizard of Oz and The Grapes of Wrath, did those works influence your design process? What are some other works that you looked to in finding the visual foothold for this book?

MS: Other than for the Wizard of Oz nightclub scene, it didn’t really influence me. Initially I looked at a load of vintage advertising, work by Coby Whitmore, Norman Rockwell, Austin Briggs and so on, as I wanted it to have a kind of retro ’50s look, and to some extent that influence continued, although it may not be that obvious in the finished artwork! As I said previously, corporate ID and infographics played a large part, but I also Looked at other designers, in particular Saul Bass, David Carson, and Jonathon Ive. I guess The Truman Show influenced me to some extent too.

There’s a lot in “Friendo” that is very much grounded in the news. Stuff like the wildfires in California to celebrity culture to the constantly creeping advancement of technology and its ever present influence in our daily lives. How did you begin to design this world that is slightly off kilter from our own present-day world, but still fantastical and futuristic?

MS:I knew from the start I wanted to take a U-turn stylistically, so out went the heavily rendered/textured work, and instead I approached this with minimalism in mind. This approach is certainly influenced by the infographics and minimalist design, but equally I’ve always loved the work of David Mazzucchelli, David Aja, and Steve Yeowell, and it’s that clean line approach to comic art that seemed to fit so well with the design aspects I’ve mentioned.

Continued belowI wanted to create an LA that’s unnervingly artificial, with a strange plasticity about it. Almost as if it’s a film set rather than a real place. A place well outside of anywhere else. You may or may not have noticed, but no shops other than the Cornutopia stores have any branding on them, or that for the most part the money is just plain green sheets of paper. I guess I’m trying to make the city and everything in it as faceless as possible.

Also, along with the amazing and vibrant colour work Dee has done for this series, I still wanted to retain an unnerving bleakness throughout, and that’s also where this unbranded plastic world comes into play. In my head, even the palm trees are 100% plastic.

What makes working on “Friendo” different than some of your other work like “Punks Not Dead” for Black Crown/IDW or your recent Marvel cover work?

Practically speaking, just doing the linework has meant it looks completely different to the other work I’ve been involved in. Dee Cunniffe, who has done such an amazing job at colouring this book has been really important in giving “Friendo” such a unique look. Before he started work on “Friendo,” Alex’s only stipulation was to give each scene the colour palette of some sickly cocktail, and that’s just what Dee has achieved. It’s been a great experience to see how Dee’s interpreted my linework, and I’m over the moon with the results.

Finally, what are you most looking forward to drawing or designing or creating as this series moves forward?

MS:Alex has written some great scenes in issue 3 that I’m drawing at the moment, and one in particular that will be a complete departure for me. I can’t tell you what that is though! I know for a fact that issue 5 will have a belter of a finale, but again I can’t tell you anything about it!

All I will say is, there’s some pretty weird times ahead for Leo and Jerry.

Well Alex again thanks for taking the time to talk to me I do really appreciate it. So first off, what is “Friendo” about to you? Thematically, story wise, whatever, what is at the core of this story and what are you trying to capture here?

Alex Paknadel: Okay. I wanted to address the idea of consumer society falling apart before our eyes. I think what’s interesting about our particular historical moment is that we have this renaissance in advertising and product design just as consumers’ disposable income is plummeting. In other words, companies’ ability to make people want things has massively increased, but consumers’ ability to buy those things has massively decreased. On the one hand, this is a time of unprecedented bounty; we have access to more than we ever have, but, at the same time lifespans and life expectations are dropping. What does that do to a population; that sense that it’s all there for the taking but not for me? With “Friendo,” I’m interested in that inflection point where we have so many carrots that are being dangled in front of us and, at the same time, our opportunities to grasp those carrots are being stripped away. To my way of thinking, that’s a recipe for disaster. To me, and I hope this is clear enough, that’s kind of what “Friendo” is about. I’ve got this protagonist called Leo. He comes from a very stringent religious background, and he moved to Los Angeles to become an actor, thinking that it was all attainable; that his dreams were within reach. They weren’t.

Another interviewer asked me the other day, “Why did you set it in LA?” I think it was because what’s really interesting to me about Los Angeles is this idea that you can be within 30 feet of the lifestyle you want, yet it might as well be a million miles away. Everything’s seen through a plate glass window, but it’s just tantalizingly close. Our protagonist, Leo, is given these augmented reality glasses called Glaze. I’m not being particularly creative with that. I’m sure people can look at the provenance of that and draw their own conclusions. When Google Glass came out, I kept thinking…this was a long time ago now, but I kept thinking, how are they going to use that as a marketing or an advertising channel? It must be in the works. I was actually working for a marketing company at the time, and I concluded that the most effective thing they could do was have their marketing solution be an actual augmented reality person. Rather than having all these push notifications swimming into your field of vision like, “Hey, go into Arby’s. 10% off coupon for Taco Bell” or whatever, what if you just had a friend rendered into your environment who would say, “If you head into Arby’s, I can get us 15% off, no problem. Just follow me.” It would be this kind of demonic, hectoring presence. Then I started to think about how creepy that would be.

Continued belowWilliam Gibson, I’m probably paraphrasing here, but William Gibson has this wonderful expression, “The street finds use for everything.” Or something like that. “The street finds its own uses for things.” What if an augmented reality friend became an enabling mechanism? If all it wants is to make you buy stuff then it’s kind of inherently psychopathic, right? What if you used some kind of 80s MacGuffin like a bolt of lightning to make it malfunction so all of its ethical protocols, such as they are, just dissolve? Then you basically have a weaponized devil on your shoulder; one you’ve purchased yourself. And what are the narrative possibilities of that?

Sorry, that was a very roundabout way of explaining the thing, but that’s pretty much the essence of it.

[Laughs] No, no there’s so much to unpack there! You’re talking about rampant consumerism and about advertising, and about all these different things. I think the thing that stuck out to me the most reading the first issue is, this relationship between rampant consumerism and capitalism and also religious fundamentalism. You talked a little bit about how Leo has this background with that, his father is a pastor/preacher/what have you. These ideas about religious fundamentalism, are these things that you are pulling from your personal experience, or just ways that you’re looking around the world and seeing that sort of religiosity inspiring things? What is it about those sorts of ideas that are interesting to you?

AP: To answer your first question, no, I didn’t have a religious upbringing. I don’t have a religious background. In fact, it was almost kind of militantly atheist, by the way, which is not to say that I have a problem with religion, you know what I mean? But I think where I was going with this was, the correspondence is there and it’s intentional. If I dig into that, I was trying to force a comparison because it seems to me that what’s happening is that…well, this is one reading, and it’s by no means authoritative. With the retreat of religion, certainly in Europe in the mid-20th Century, and there are various reasons for that: the Enlightenment, modernity, whatever. There was an expectation that the market would replace it. Certainly, that reaches its apex, doesn’t it, with [Francis] Fukuyama’s pronouncement of “the end of history “in the late 80s, early 90s. This idea that free market capitalism and liberal democracy, which obviously go hand-in-hand, we now know they don’t, but this idea that they go together like birds of a feather. Liberal democracy and free market capitalism would be, if you like, the binding albumen of globalization, that we finally had a belief system, an orthodoxy, that would carry us through to the next stage of our evolution or whatever, or even the final iteration of humanity, the last man. That didn’t happen. I’m generally very positive about globalization, but the attempt to turn it into a heroic narrative was spectacularly wrongheaded. And now here we are, I guess.

The funny thing is…I was speaking to a friend about this the other day. It’s kind of baked into “Friendo” as well. I think one of the reasons why you’re seeing all these malignant extremisms popping up all over the place – fascism, romantic nationalism, toxic communism, and whatnot – is because free market capitalism isn’t a heroic narrative, whereas those abominations certainly are. All political extremes, as scary as they are, are undeniably heroic. At both ends of the spectrum, left and right, you have the plucky underdog and the evil enemy (within or without) who must be vanquished in order for history to end and the quote, unquote “true people” – whether that be the volk or the proletariat – to become the inheritors of paradise. It’s pretty irresistible because it ennobles the suffering of ordinary people by making them part of this epic struggle between good and evil, but unfortunately it usually leads to purges, pogroms and cultural revolutions. Now, these heroic narratives can’t get any purchase in the popular consciousness when markets are functioning properly because the majority of people have full bellies and a realistic shot at a few of their life goals; however, when markets cease to be an effective method of distributing wealth to as many hardworking people as possible, that’s when you see that heroic nonsense bubbling up to the surface again.

Continued belowI guess what I’m wondering is if we see free market capitalism as a tide, the tide that lifts all boats, what “Friendo” is attempting to address is what people do when the tide goes out. What’s left? I think what’s left is, for want of a better expression, psychosis. Going back to Leo, this is someone who had a certain apprehension of the way the world worked, and within that he would have his own comfortable little heroic narrative. At the end of it, he would become a famous actor, but then the tide went out on that. Now, he’s been abandoned. He’s been abandoned by religion. He’s been abandoned by the market, so what’s left? I guess what’s left is radical nihilism.

It’s not abundantly clear in the early issues, but certainly as we go on and the back half, certainly, of the series. You start seeing front and center that Leo’s relationship with Jerry is all he has. You have this demonic figure saying, “You need more stuff. You need more stuff,” and Leo doesn’t have any money. I won’t give too much away, but I’m sure your readers can draw their own conclusions. What do you do when you want stuff and you don’t have any money? Things go off the rails very quickly, and the whole thing sort descends into this, I hope, funny but also very anarchic and unpleasant road movie.

But I think you’re absolutely right to see the correspondence between religiosity and capitalism, certainly. I’m wondering what happens when all of these narratives are depleted, and what are you left with?

You’re talking a lot about narratives, and what sort of happens when all these narratives come out from under you. There’s a lot of different narrative influences here in the first issue, and I would assume probably in the rest of the series. You get stuff from The Grapes of Wrath, The Wizard of Oz, you even open the issue with a TS Elliot quote. What is it about these other works that inspired “Friendo,” and are we going to see some more of those influences as we move forward?

AP: Again, just to loop back to what I said originally about Leo, I was kind of thinking about, again, going back to why I set it in Los Angeles. This happened a while ago, it occurred to me that The Wizard of Oz and a lot of [John] Steinbeck’s stuff, but principally The Grapes of Wrath, structurally and thematically are strikingly similar, right? I know that [Frank] Baum wrote The Wizard of Oz long before the Dust Bowl, but I think it’s fascinating that you do have that freak weather system, like in the Midwest, that forces a relocation to a magical realm that ultimately after the quest is finished turns out to not be everything that it should be, right? You peel it back and you have the wizard behind the curtain, but also when you turn up in California, it’s not this land of milk and honey. Actually, there are these labor camps and this terrible exploitation.

I was just sort of thinking about all that in terms of Leo turning up in LA – another weary pilgrim tempted out of the desert by the searchlights – believing it to be the promised land, and it disappointing him. But I’m not in any way comparing myself to Steinbeck and Baum. That would be insane. But in terms of influence, you pull back the curtain and you see that the wizard isn’t a wizard. You see that your dream is not going to deliver, so where do you go from there? I guess there’s something in the water, but I think we’re seeing a lot of that at the moment; people kind of questioning the value of mindfulness, and positive thinking, and vision boards, and all this stuff. What happens when people finally realize that they actually have finite agency?

Don’t get me wrong. You have to meet the world halfway, of course you do. But when the resistance you encounter, in terms of manifesting your will, is…when you realize that resistance is actually enormous, what happens then? Some people carry on regardless, and for some people, there is this psychological retrenchment where they turn inwards and become terribly resentful. Leo is one of those people. We join him during a massive identity crisis. If he’s not an actor and if he’s not a dutiful son then what is he?

That’s where the T.S. Elliot quote at the start of the book, “The desert is in the heart of your brother” comes in. Coming back to Los Angeles, I was really struck by …you must have seen Chinatown, right? If you watch Chinatown, Robert Towne’s done this really interesting thing where he constantly plays with this idea of Los Angeles as this schizophrenic city that can’t decide whether it’s a beach or a desert. Even down to mentions of Seabiscuit – think about the implications of Seabiscuit – something kind of dry and flavorless but juxtaposed against the sea. It’s a kind of undecided, liminal space. I guess what I was trying to do with that is explore this idea that you have someone – our protagonist, Leo – who can’t decide who they are in a city that cannot decide what it is. And actually, that indecision is dynamic. If it ever decided what it was, it would cease to be that thing.

I know it all sounds very highfalutin and pretentious, but I promise you, when you read the book, you’ll blink and you’ll miss all this. It doesn’t disrupt your reading enjoyment at all. It’s just there for color, really, but I just wanted to make the book yield multiple readings.

So what’s the collaborative process with Martin like? How has that shaped how you’ve been writing “Friendo?” How have you been able to build off each other? What’s that been like?

AP: It’s been amazing. The thing is, Martin and I have actually been trying to get the book off the ground for literally years. We first met, I think, at a London film and comic con, maybe four years ago? It was when “Arcadia” was being put together, so maybe 2014. Initially, I wanted it to be the follow-up, so he’s really been there from the beginning and we kind of thrashed it out together over a couple of boozy lunches. He’s not just the artist. The artist is the co-author anyway, but he’s been there conceptually from the beginning, making suggestions.

Also, his early visualizations of the characters, which I got within a couple of months…he was working on “Death Sentence” with Monty Nero at the time, but he was sending through all this concept stuff and that helped me really fix, particularly, Jerry, actually. It really helped me fix Jerry in my mind. You’re not really aware of the influences, and Martin wasn’t, I don’t think. Initially, I envisioned Jerry to be this cartoonish Elvis figure, like Elvis from Hell. But Martin went with this very wizened, very skinny sort of representation. I think the rationale behind that, I’ve never really kind of went into detail with him, but I think he wanted to have Jerry be like a visual representation of hunger. You know what I mean? He’s constantly starving for money, for stimuli.

We managed luckily to get André Lima Araújo and Chris O’Halloran to do a variant cover for us, and André drew Jerry on the cover. He reached out to me and just went, “Dude, this is Richard E. Grant, like in Withnail and I. “ I went, “Oh my god, you’re right.” It’s true. The look of Jerry, it’s basically Withnail in California in a Hawaiian shirt, and I couldn’t think of anything more perfect. I know Withnail in the movie…I don’t know if you’ve seen it. Have you seen it?

I haven’t, no.

AP: Dude, it’s fantastic. There’s an argument for it being the best British movie of all time, but it’s also the funniest. It’s a British buddy movie, basically, set in the ’60s between two out of work actors, one of whom is this unconscionable parasite who is just perfectly selfish. That couldn’t be more perfect. I don’t know. There must be something in the groundwater or something, but Martin chose to depict Jerry as that kind of parasitical character. Couldn’t be more apposite.

Working with Martin, it’s always a dream. It’s one of those things where I have to share him with the egregiously talented David Barnett on “Punks Not Dead.” And that’s fine, but I’m sure at some point it will descend into violence because I’d love to work with Martin forever. It’s interesting for this one because he told me a while ago that he wanted to, because most of the stuff he does is digitally painted, so he takes care of everything himself, he said for this he wanted to experiment with a new way of working. So this is actually virgin territory for him in the sense that he’s just provided the line work, and then we got the incredible Dee Cunniffe involved. He does a lot of work with Donny Cates, like on “Redneck” and stuff.

Continued belowDee really is far more than a collaborator. He does so much to bring the book to life. His work in issue one, particularly on the sequence during the brush fire, I think is absolutely exquisite. But you’ll see in issue two, he’s taken this really, I can only describe it as, the color palette that he’s using in issue two just really reminded me of David Hockney. I said elsewhere it’s like David Hockney’s pool paintings from Hell. The sunlight is just a little bit too strong. The skin’s just a little bit too smooth. Dee’s doing that with color. The effect is absolutely extraordinary. Once we hit issue two…issue one, I adore issue one, but I think when we hit issue two, I think that’s when the team is really finding each other’s feet and it’s where we start really firing on all cylinders.

That’s really amazing. Well Alex, we’ve been going for awhile now, to wrap up, what are you the most excited about going forward for “Friendo,” and is there anything else you want to say or promote that we haven’t touched on?

AP: “Friendo” is out September 26th. I hope everyone enjoys it. I know I’ve probably done the book a disservice in that I may have misrepresented it as this very dry intellectual exercise. I promise you it isn’t. At core I say, if you enjoyed RoboCop, the original RoboCop, I think you’ll enjoy “Friendo.” It’s the same very cynical, very mordant sense of humor with lashings and lashings of ultraviolence. There’s as much to entertain as there is, hopefully, to provoke.

Apart from that, what I’ve got on, I have just taken over a Lion Forge superhero book called “Kino” from Joe Casey, which I’m very excited about. It’s a British superhero who’s been held in virtual reality. I know that sounds wacky. This guy’s been given a false past, basically, a sort of Kirby-esque, uncomplicated superhero origin story that’s only ever taken place in his mind. But now he’s back in the UK and things are not well, all is not well politically. The country’s going through these nationalist convulsions, and he has to come back to that. I’m very excited about that. I’m working with Gail Simone, who’s just assumed responsibility for architecting. Sorry, I’m using architect as a verb. That’s a terrible thing. She’s taken the reins of the Catalyst Prime universe, which is Lion Forge’s in-house superhero line. We’ve spoken a couple of times, and she seems to dig the direction I’m taking it, which is enormously flattering. Her suggestions are being folded into the book and everything, and I’m beyond excited to be working with Gail. She’s got some very, very big ideas for the Catalyst Prime universe, not least in terms of wiring the thing together in really exciting ways. I can’t really talk too much about her plans, but I have a feeling, not through my efforts but through Gail’s, that the CPU as they call it, the Catalyst Prime Universe, is going to be making quite a big splash into 2019 and beyond. I think my first issue, which is issue #10, comes out in November.