In today’s Artist August, we bring you a real treat. We had the chance to talk with him while doing press for the book “Ballistic,” but today Darick Robertson chats with us in a different fashion — that of a career retrospective.

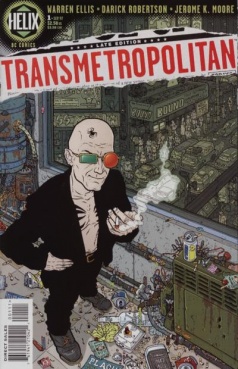

For me, this is big for two reasons. One, because it’s Darick Fucking Robertson and his work is awesome because hello have you seen it? But two, Darick’s story of breaking into comics (like all stories, really) has a very unique flare to it; breaking in at a young age with some creator-owned work and for-hire gigs, Robertson made a huge splash teaming up with Warren Ellis for “Transmetropolitan.” And I mean huge — “Transmet” is a classic, definitive Vertigo series in the same vein as “Preacher” or “Sandman” in my eyes, and it is one of those books that continues to be worthwhile reading even years after its initial publication (which makes for interesting lookbacks given the futuristic nature of the series).

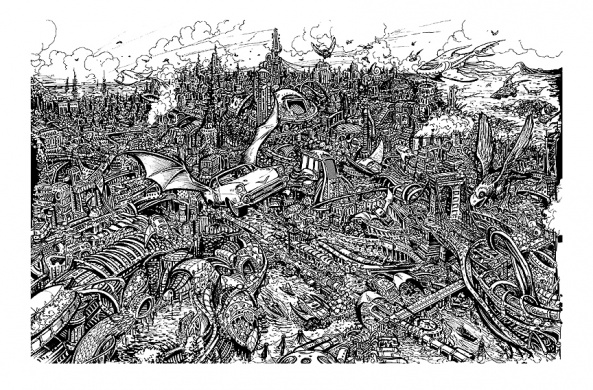

Robertson was able to define a voice for himself with his art at an early age and now, roughly two decades later, he’s still going strong, creating some of the most detailed and in-depth layouts and landscapes we find in comics. Just look at the above splash from “Ballistic” #1, which debuted last month; it’s a madman’s gambit of a living, breathing and hateful city that is brimming with life in every corner, and it’s this kind of artwork that makes Robertson’s style instantly recognizable and unmissable.

Not to mention his work on “The Boys” or “HAPPY!” or any number of series, really. My ultimate point being: Darick Robertson is pretty damn great.

So sit back and enjoy our chat with Darick as we look at his early days in comics, his time on “Transmet,” and what the future holds for him. And also what happens when Spider Jerusalem and Billy Butcher meet up — honestly.

We’ll start with an easy question: Darick, why comics?

Darick Robertson: Comics and visual storytelling were something I was always pulled towards, creatively. I made short films with a Super 8 Camera, played around with flip books and studied animation, and ultimately found that comics was the most fulfilling way of telling a story. I can create an entire world within the format of comics. I get to direct, light a scene, design technology and make my characters perform.

I fell in love with the medium when I was about 10 years old, and stapled together some typing paper and made my own comic book. I was hooked ever since and constantly found sources that could push me to improve, dreaming of the day my skill level would reach professional. I did other things during that time, performed music in talent shows, acted in plays, but comics always felt like that would be my thing and what I wanted most.

What was your first experience with comics as a reader and a fan?

DR: My earliest memories of comics were random issues I would find at the barber shop my Dad took me to, and old comics that people would give me, often missing covers, so I had no idea what I was reading half the time. It almost made it more fun trying to puzzle out what I was enjoying.

Your first published work was a comic called “Space Beaver,” about a beaver in space who takes down drug lords. As a fan of cute anthropomorphic animals doing violent actions myself, where did you come up with the idea of Space Beaver?

DR: Space Beaver was born of a random doodle on a note pad during an after school job. The name popped into my mind and I started designing characters as doodles. I was digging popular comics with anthropomorphic animals at the time, most notably Mike Mignola’s “Rocket Raccoon” and DC’s “Captain Carrot and The Zoo Crew,” featuring Scott Shaw’s awesome work and designs. I never really saw Space Beaver as going anywhere, I truly never thought that would be my break into comics, but I had summer school that year and to pass the time, I began a free flowing, panel by panel story that I was creating in ball-point pen in class, and what essentially became the first 8 pages or so of Space Beaver #1. But I learned to draw on proper bristol board and use real tools for the stuff that got published.

Continued belowHow did it feel to use what is ostensibly a ridiculous concept in order to break into the industry? Did it feel gratifying to take this work and make a career from it?

DR: Ridiculous? Come on, are you telling me it’s any less ridiculous than other stuff that was on the shelves in 1986-1987? “Black Belt Radioactive Hamsters”? “Fish Police”? Hell, I just fell into a trend that I wasn’t even aware was happening at the time. It’s why Space Beaver was published! There was a black and white comics bubble happening in the wake of the juggernaut that the “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” had become and everyone was looking for the next one, and that’s how I got a break.

My first love and goal was to draw super heroes. I loved Teen Titans, The Flash, Batman, Justice League, Spider-Man, X-Men, and all I wanted was to get my break into Marvel ad DC. But in those days, going to Comicons was a way of meeting editors and publishers, and finding work. And since I was a published writer and artist, I was able to get passes and invitations to Comicons.

You broke into the industry at a fairly young age yourself (if my research is correct, you were 21). Given that most aspiring creators are still often just dreaming of comics at that point, can you tell us a bit about your early days working for Marvel and DC and what it was like for you?

DR: I was 17 when Space Beaver #1 was published and I was creating pages in my high school senior year art class as my project. My teachers just let me do my thing, gratefully. It took me until I was 20 to get my first gig at DC comics with “Justice League Quarterly” #4.

Marvel and DC were just entering the second economic bubble fueled by the departure of the 7 artists from Image that went on to found that company. I had arrived and it was everything I dreamed working at Marvel and DC would be. I had no idea by 1996 Marvel would be bankrupt and sales on titles would plummet as the industry bubble popped. It was a lot of fun in the early 90’s. The older guys knew it wouldn’t last and a lot of us younger guys thought the party had just started. I learned from that time to love the work for what it is, not what you get from it. I was in my 20’s, on my own, in my first apartment and all the time and energy I needed to work like a mad man, and I did. I was constantly drawing covers, new characters, trading cards, toy packaging art, posters… the work was steady and rewarding. And Marvel paid out royalty checks in those days, so a three issue stint on Wolverine made my year. But companies like Malibu were popping up to compete and then disappearing with things I created for them that I thought would be my steady gigs. So that rise and fall was a hard life lesson. By 1996, I was ready to get out of the industry.

Your first big creator-owned piece after breaking in was the monumental series “Transmetropolitan.” I can imagine debuting a creator-owned comic like that was scary, but can you remember what was going through your head a bit when you decided to work on this series over something for-hire?

DR: It wasn’t scary at all. It was a relief! What no one knows is how something is going to impact the audience when they’re creating. I was ready to leave comics altogether when Warren called with the Transmetropolitan proposal for what was then another new line of comics, a new Sci-Fi based sub company of DC, “Helix” comics, that ended up going bust 6 issues into Transmetropolitan’s run. Something that I was used to. But a good friend of mine reminded me that doing something original would supercede being another name on a list of people that worked on characters for the Big 2.

Warren’s concept was great, and he wanted to collaborate. He was open to a lot of the ideas I began bringing to the art and designs, like Spider’s Three Eyed Cat, Spider’s glasses, and the sling bag he’d have all the time, Sex Puppets, Buy-Bombs, and we’d start laughing on the phone and believed we’d be lucky to last four issues before they cancelled us. No one was more surprised than we were when the book outlasted “Helix” and was adopted into Vertigo and went on the garner multiple awards and nominations.

Continued belowWhat was the working relationship like for you and Ellis while working on “Transmet?”

DR: Those early days were a lot of fun. The creativity was free flowing. I believe Ellis and I were both caught up in the machinations of the industry, and approached the book from two different perspectives. What we shared was a common frustration and wanted to create something wry and topical. I love Spider Jerusalem and he was the punk rock bad/wise ass I always wanted to grow up to be.

Looking at some of your earlier work, pre-“Transmet,” I’d think it fair to say that your art evolved exponentially over the course of the series. Do you think working on a steady series like this afforded you opportunities other gigs might not have?

DR: I think a lot of my pre-Transmet work was a product of being in a demanding industry at a time when product was king. I was trying very hard to compete in a business that had lured me in by reading things like “Watchmen” and “The Dark Knight Returns, “Daredevil: Born Again” and “Batman: Year One”.. only to watch the Big 2 fall in love with changing all their iconic characters, killing Superman, breaking Batman’s back, creating a myriad of different Spider-men (I was a part of the Clone Saga!).

I worked on a series called “Spider-Man: the Final Adventure” and it certainly wasn’t. In that time I got to draw Aunt May’s eulogy written by Stan Lee himself and inked by my hero, George Perez. I even wrote and drew some stuff, including a Spider-Man story inked by Jimmy Palmiotti. But at the same time, everything seemed more about how fast we could produce the stuff, not how great we could make it. So getting off that train and doing something original was a welcome departure.

I thought Transmetropolitan was going to end my career, and instead, it gave it new life. So all I was doing before Transmet was trying to please my editors and create competitive work that would get me more gigs on stuff like X-Men, so I could keep working. Ironically, Malibu offered me a chance to write and draw my own series ‘Ripfire’, but it never got beyond the preview stuff. The company folded and I regret to this day that I passed on a run on Excalibur, because I didn’t know who the writer would be, and it turns out, it was Warren Ellis! I also felt that following Alan Davis was going to be too tough, (Having learned what it’s like by having followed Bagley on New Warriors) but looking back, I wish I’d taken that gig.

Looking back on it now and seeing what a staple for comics and Vertigo that “Transmet” has become, how do you feel about your work on the series through the telescopic lens of passed time? Is there anything you’d re-do, if you had the chance?

DR: I’m proud of the work on Transmet and gratified it is finding new audiences and readers, now over ten years since we completed it. My only regret was that we could never work the schedule into a rhythm that would have allowed me to ink it myself. Rodney Ramos did an amazing job, but we were always under the gun and I always wished that even as a duo we’d have had more time. Sometimes though, I think that frenetic energy was what that book needed.

You and Garth Ennis set up a rather fruitful relationship, working on books like “Punisher,” “Fury” and “The Boys,” which was your second major creator-owned title after breaking in. Having done a fair deal of superhero work, what was it about “the Boys” in a creator-owned capacity that excited you about the project?

DR: “The Boys” was about looking at superheroes a different way. I still wanted to draw and create them, and Ennis wanted to turn over the rock and take a Dr.Wertham kind of microscope to them and expose the plot holes into sinister black ops and conspiracy theories, existing in that world

I always thought his scripts were fantastic, so I was eager to create something original together. I was drawing superheroes, it was creator owned, for Wildstorm at the time, and Ben Abernathy was editing. It seemed like a perfect gig.

Continued belowIn any way do you see your work on “The Boys” and “Transmet” relating on a deeper level? Is there anything you did particularly different on either title, or perhaps even something you did on purpose in the same way?

DR: I just tried to tell a great story and I try to create worlds that fit the tone of the book. With “The Boys” I got to ink my own stuff every month, as I’d wanted to do with “Transmet,” and until the scheduling nightmare brought on by our cancelation at DC and reboot at Dynamite, I was really enjoying that aspect of the book.

We talked a fair deal about BALLISTIC in our previous interview so I won’t get too much into it, but I forgot to ask then: as a fan of characters and properties yourself, do you have any interest in doing more for-hire comic work? Or are you primarily focused on your own titles right now?

DR: I am mostly interested in creating original stuff now. Working on “HAPPY!” with Grant Morrison for Image comics was such a pleasure and their business model is such a good fit for me, I see myself doing more of that. But I still love the Marvel And DC Characters and am working with DC right now on some new stuff. I just don’t see myself as a monthly, mainstream superhero guy anymore. ‘The Boys” probably tarnished that for me.

With two massive creator-owned series under your belt, how do you feel your impact has been in comics so far?

DR: I’d actually count “HAPPY!” as the third creator owned series that hit, as it did and is doing quite well. Not as lengthy as ‘The Boys” and ‘Transmet,” but very well received.

I don’t know how to measure things like my “impact” on comics. Most of the time I get people who seem to love the writers I’ve created with and treat me like I won some sort of contest to co-create the stuff with them that I have. I get questions about working with them, but I don’t often see them questioned about working with me, so I don’t know. I produce a lot of work, and I’m not that arrogant about my career that I think I make an impact on anything, really, but I’m glad people like my stuff, and grateful when it sells, and worry about when it doesn’t anymore. I hope to have a career like Jean “Moebius” Gerard and leave a legacy of good work behind me, no more than anything else I achieve. I just want people to have a good time reading anything I’ve drawn.

My new project is “Ballistic” with Black Mask Studios, co-created and written by Adam Egypt Mortimer, with the first issue out in July. I am finally inking my own creator-owned future world.

With today’s modern technology, artists have the opportunity to explore a digital medium in addition to traditional pens and inks. Is this something you’ve explored yourself?

DR: I use the computer to finish off files and add digital effects before sending stuff off to the colorist, and I really enjoy that level of quality control over what people get. But as far as moving to Wacom tablet, I don’t see the appeal. There’s something honest about taking a break from a computer screen and creating with raw tools and getting my hands dirty. Maybe because my Dad was a mechanic and liked working with tools and getting dirty, that it seems a more valid form of work to me when I do that.

I also love having a physical piece of artwork in my hands when I’m done. I’m blown away when I see the stuff my friends create digitally, and my hero Brian Bolland gave up pen and paper years ago, but so far, at least until I get one and become addicted to it, I still like working the old school way. But I love the advances technology has brought to delivery and such. Being able to scan something and put it into the hands of the letterer and colorist myself, even though they’re miles away, within minutes of completing the work, is wonderful. I remember the days of rushing to get to the Fed Ex before the drop time and worrying that it would get damaged or lost in transit. I do not miss that.

And now, the ultimate question: what do you think would happen if Billy Butcher met up with Spider-Jerusalem one evening?

DR: I think they’d ignore each other and that Butcher would mercilessly beat the hell out of Spider if he said the wrong thing to him. Unless Spider was dressed up and on a drug that made him think he was a Super Hero, I imagine they’d walk right past each other. Then again, one of them had to travel through time to meet up in the same universe, so what the hell are we talking about here?