Cory Doctorow, writer of “Homeland,” “Little Brother,” “Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free: Laws for the Internet Age,” editor of Boing Boing, Internet activist (and yes by that I mean he works to make the Internet work as an activist) and more, has written his first graphic novel, “In Real Life.” “In Real Life” is adapted from Doctorow’s short story “Anda’s Story,” (which can be found online under the CCL). It is co-written and beautifully illustrated by artist Jen Wang (creator of “Koko Be Good”) and debuts on October 14th from First Second Books.

In the introduction to “In Real Life,” Doctorow addresses how this graphic novel will cover similar themes of his prior works. He states, “‘In Real Life’ connects the dots between the ways we shop, the way we organize, and the way we play, and why some are rich, some are poor, and how they seem to get stuck there. I hope that readers of this will be inspired to dig deeper into the subject of behavioral economics and to start asking questions [like Anda] about how we end up with the stuff we own, [and] what it costs our human brothers and sisters.” How? He creates a graphic novel that reads like a game-walkthrough and heart-wrenching confessional tale.

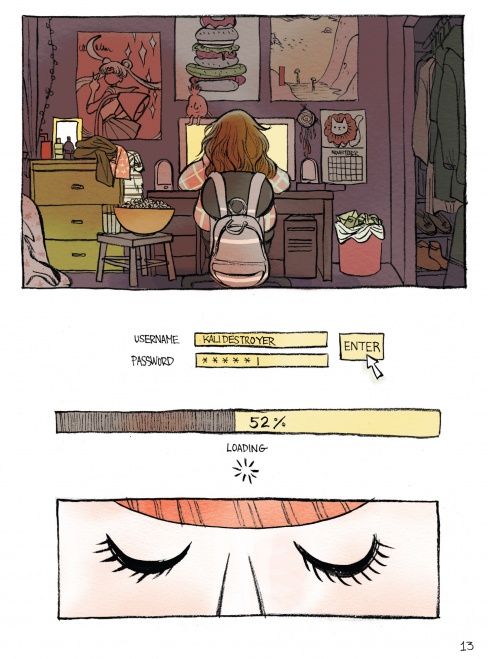

“In Real Life” takes us on Anda’s journey through joining an online MMO RPG gaming community called Coursegold Online during her awkward social teenage years. In Coursegold Online she is a leader, slays monsters, wields an axe and makes friends from all over the world. But it is when she befriends a gold-farmer in game, who turns out to be a poor Chinese boy in the real world, profiting off the illegal selling of valuable objects in the game to support his real-life family that Anda begins to question what rules to follow.

At NYCC ’14, Cory Doctorow sat down with me to talk about the process of adapting “Anda’s Story” from the page to the palette.

In Real Life was adapted from the short story “Anda’s Story,” so my first question was what was the process like translating one of your stories into a visual medium?

Cory Doctorow: I have to give credit where credit is due. Jen did all the heavy lifting.

She took my story and wrote a script. I edited it, but it was so good there wasn’t a lot of editing involved. It was like the world’s least dramatic collaboration. It was super smooth. For all I know Jen struggled miserably with the material and cursed my name every day, but from my perspective I edited an excellent script, had a few minor disagreements, and then had this brilliant graphic novel show up in my email box. I picked Jen out of a lineup of artists that First Second sent to me. At first, I hadn’t realized that she was the “Koko Be Good” person. It wasn’t until I got the finished book, and read her bio that I realized that she was the person that wrote “Koko Be Good.” I reviewed that book. I loved that book. The name of that book always stuck with me, but not her name. Once I realized that that was her, I felt so grateful and so honored.

One thing that stood out to me when reading “In Real Life” was how it distinguished the “real world” life from the Coursegold world through Jen Wang’s choice to use two different color palettes. That’s such a smart choice (sighs in awe)! What things for you surprised you through this process? What things were you like well that’s a good telling method of story that wouldn’t have occurred to you otherwise?

CD: The palette is a great example of the kind of shorthand that you can do with graphics that you can’t do with prose. And I think that all novels share a certain science-fictional element, whether or not they’re science fiction which is that they pretend that you can be inside of someone’s head and know what they’re thinking which is something that no one in the history of the world has ever done. They all have a science-fictional pretense to telepathy. And that’s not what graphic novels do, with the exceptions of the odd-thought bubble or with films with the exception of the odd-voice over. They are a visual medium. I’m not visually acute. I see poorly. I pick out details poorly. I’m color-blind. I love reading graphic novels. I can’t draw, so for me seeing the work translated beautifully on the page is like sorcery.

Continued below

The way Jen was able to control the rhythm of the story, especially with the dialogue was so nice. In prose you really strive to do that. Although dialogue is really important to prose our tool-chest is limited. The ellipses, the occasional em-dash…but we don’t have that beautiful tool-kit of being able to space things out and to transpose facial expressions, and to change the lettering. Just the liveliness and the sprightliness of the dialogue was really wonderful for me.

The character design overall was not how I saw it in my mind’s eye, but it was how I wished I saw it. I wrote “Anda’s Story” in 2002 thinking about EverQuest and obviously that aesthetic is generations behind us now. And I like that we didn’t get Warcraft. What we got in the game design was something different enough. It has that thing that I try to do with my prose settings which is to be indeterminate, possibly counter-factual, presenting a mirrored future that might be the present, that might be tomorrow, that might be ten years from now. I could see a game studio produce Coursegold online now, or never producing, which I thought was great, just great.

I especially like her noob characters. The experience of generic characters is really important to how we experience games or social media. The Twitter egg is such a big part of how we interact with characters in the real world. I think Jen really nailed a great way to depict a noob in a game.

In “Anda’s Story” there’s a point where she decides to join Liza and her crew is because she has a “sensible avatar” and wasn’t wearing “pointless leather bikini armour-wear, or Bintware.” Were there ever moments in designing these avatars or even depicting these female characters as people that you had a dialogue with Jen on not doing that?

CD: No. Jen just got that.

Oh. That’s fortunate.

CD: I think that anyone with any kind of sensitivity that read the story would have understood what the redlines would look like. And Jen is good, so no, there were no problems there for that kind of depiction. My wife is the visual one in our family, and she’s also the gamer. She’s the first woman to ever play in the British National Quake team, and was a game publisher for Channel 4, she was the Vice President of Digital Content for BBC Worldwide, founded the blog Wonderland, and is the founder of MakieLab. So Alice was my reality check in all of this, both in the story and in the graphic novel adaptation, the character sketches, and designs.

Was there specific feedback that Alice gave within the checkpoint stages?

CD: When we were looking at different character designs, she was really good with that. She has a great graphic sense, so she was tremendously helpful in picking the artist to work with, and I really trust her judgment. She has been a graphic designer, and have overseen game and graphic novel production, so I really trust her judgment in this.

I’d say. In your introduction you state, “When you put economics and games together, you find yourself in the middle of a bunch of sticky tough questions on politics and labor.” When it comes to the economy of CourseGold Online’s economy system, I’m curious, was it modeled after any particular economy or any real-world economy?

CD: It’s the “always keep your towel” theory. You put in enough concrete details to imply that you got the whole thing worked out. The concrete details that I wanted to put in were places where there were obvious allegories to existing economic realities, especially some of the weirdest elements of it.

In depicting the limits and rules of that system, were you looking towards any specific gaming and/or political systems?

CD: I think of the greatest ironies in the relationship between games to gold-farmers is that the basis for game companies asserting primacy in control over how you play and the rules and whether they kick you out, or let you in, is property. They say, “It’s our property, we made this world, you have to play by our rules.” But when you assert property, when you say, “This is my gold.” They say, “Oh no, that’s not your property.” So property rights are the best solutions to all problems unless those property rights interfere with the rich and powerful’s property rights. And I think there are parallels to that in the real world, in the evictions of people in sub-prime situations and civil forfeiture and lots of other socially unjust relationships that people have with the state. In the real world there are very rich people who go bankrupt who suddenly are able to keep their horses and their second houses and poor people go to jail because they can’t pay the liens in their property, yanno?

Continued belowHow did you use gaming mechanics as a way to build characterization? How did you choose what moments to show in the CourseGold online game to help describe the characters and the situation?

CD: I think it was all Jen. She doesn’t stray too far from the story [for its key moments] as it is.

One of the nice things about using a game to try to surface these issues is that the game in itself has got some many shiny, attention-snagging, interesting, fun, visual action-oriented things that also chime with gamers. So we talk about BFG’s and having really triumphant total scores, and house-planning battles, and near revivals.

Have you ever played Left 4 Dead?

Um, yes.

CD: So you know that Left 4 Dead has an AI that watches to see when you’re nearly out of everything, and when the situation is entirely hopeless?

Yup.

CD: And when the situation is totally hopeless it radically increases the odds of you getting a big drop of weapons and health. And it’s the Hail Mary AI, and the drama of a Hail Mary is so intense. And so those beats are really natural to stick into these stories. They really jerk the story along.

If you’d like to see how Anda deals with the Hail Mary-like worries and woes of the gaming world as she begins to question the real world’s consequences, pull up a chair and take some time to delve into “In Real Life.” It’s a story hell-bent on asking: How does who we are determine how we play, and who is making those rules? Can we change them? Can Anda change them? Can the process of gaming give us the tools to question our own world’s economic play? Are you ready to enter Coursegold Online and see if you can find the flaws in its system and how it mirrors our world? Go on and grind out those pages, and comment here. I dare you.