As a companion to the piece we ran earlier about creator-owned comics and the reality behind making them work, we wanted to run the interviews in full that we had with varying creators and retailers on the subject. These writers and retailers can provide a lot of valuable insight into how the comic book machine really works, and with that perspective in mind, hopefully help everyone realize how important our role is as readers.

Take a look below, as people like Antony Johnston, Frank Barbiere and Jim Zub talk about what it takes to make comics work, and here in an hour, retailers will get their chance to do the same.

Antony Johnston (Umbral, The Fuse)

For your creator-owned projects, how important are sales of the title as a monthly in terms of your book continuing forward as a project?

AJ: What Brandon said last week is correct; monthly issue sales are cashflow, and from that standpoint they’re very important to a book’s health.

(Unless you’re fortunate enough to sell 25,000+ right out the gate, of course. Then none of this matters, because you’re already able to continue as long as you want.)

Now, me personally? I know my stuff attracts a lot of tradewaiters. I do everything I can to make the monthly issues attractive, and compelling, but the truth is there’s a large segment of my core audience who will always wait for the trade.

So yes, monthly sales are important, to sustain a book between trade paperbacks. But these days, trade sales are equally important, because the income from good trade sales can actually sustain a book that’s not doing so well monthly.

Umbral Vol. 1 just dropped a few weeks ago, and it was an astoundingly great deal at 6 issues for $9.99. Why $9.99? How essential to reaching a larger audience do you find releasing a reasonably priced first collection, and how important to your success in general do you find collections to be?

AJ: Well, the “$9.99 for Volume 1” thing has become a de facto standard. I think Vertigo were the first to do it regularly, on the premise that a sub-$10 cover price encourages more potential readers to pick it up. And, of course, after people read the first volume, we all hope they’ll continue to follow the series.

Other publishers followed suit, and now Image have gone on to pretty much standardise it. It’s not exactly a loss leader, but it’s in the same vein — the books do make some profit, but that profit is reduced in an effort to increase sales volume.

Why are we happy to do this? Because, as you say, we want to reach a larger audience. Reach and awareness are everything to an indie book, because most retailers aren’t going to push your book as hard as the latest BATMAN collection, or whatever.

So we have to make the trades as attractive as possible to any interested potential reader, and the $9.99 Volume 1 has proven to be a really good way of doing that. So, you know, hats off to Vertigo.

Finally, collections are enormously important, especially in the modern indie market. Take a book like MORNING GLORIES; it has relatively low monthly sales these days, but continues to shift huge quantities in trade paperback, and that’s what keeps the book thriving.

At the other end of the spectrum, books like SAGA and THE WALKING DEAD sell huge quantities of single issues, but even those pale in comparison to their collection sales.

Now, the first UMBRAL collection has only been on sale for three weeks, so we don’t yet know if our trade numbers will outstrip our monthly sales. But I’m confident that in time, they will.

AJ: With THE FUSE in particular, it was quite a while, because Justin was still finishing his last WASTELAND arc when we started planning THE FUSE. I think that was in December 2012 — Image greenlit the book in November 2012, so that’s probably about right.

I started actually scripting in May 2013, Justin began drawing in October 2013, and then we launched in February 2014. So yeah, we worked ahead quite a bit.

With such a fine line deciding success, what is your approach to promoting a new book you’re working on? As part of that, how much retailer outreach do you do to promote a book?

AJ: I tend to throw everything at the wall. I used to worry about saturation and ‘overexposure’, but I’ve been in this racket long enough to realise there’s basically no such thing.

There’s also a certain amount of ass-covering involved; like, if you don’t do as much press as possible, and then your orders are disappointing, you’ll kick yourself and think “what if?” Because, while it’s true that retailers are a comic creator’s “real” customers, it’s also true that if enough readers make a noise at their store about a particular book, it can move the needle.

As for retailer outreach… for me, being in England, it’s tricky. I’m fortunate to have a good relationship with several of the great, indie-friendly retailers over here. Those guys know me, they know they can reliably sell my work. And the UK audience has always been more receptive to non-superhero books anyway.

With US stores, it’s more difficult. For both UMBRAL and THE FUSE I emailed retailers, giving them a rundown of our plans, making a PDF of the complete first issue available, and so on. And I know Image did the same, but of course they do it for every book they launch.

That contact definitely made a difference — a few retailers told me it gave them more confidence in the book, and some stores increased orders as a result, which was great.

The bigger issue is that you’re talking to a limited audience. In the US/UK direct market, 75% of all indie books are sold by around 300 stores. Hell, the top 100 of those stores make up 50% of all sales.

Those retailers are wonderful; they’re the people actively selling diverse books to a diverse clientele, and we should cherish them, because without them there would simply be no indie market.

But we desperately need more of them. Having so few customers making up such a huge proportion of orders is simply not healthy for the industry. Hell, that kind of concentration isn’t healthy in any industry.

(And consider that the comics market is in *better* shape now than it was a decade ago. So take a moment to imagine how grim things were for those of us who survived the ’00s.)

You’re actively releasing three creator-owned books right now in Umbral, The Fuse and Wasteland, one of which – Wasteland – is even on its 55th issue. Let’s say you were going to launch another CO title. What are the biggest takeaways you’ve gotten from your CO experience so far in terms of not just finding initial success, but sustaining it?

What I’ve learned is that the most surefire way to succeed with an indie book is to first work on a superhero book. Having a high profile in the capes and punching market will boost awareness, and retailers’ opinion of your saleability, by an order of magnitude. And your indie sales will rise accordingly.

Or you can go the longer and more difficult route; keep churning indie books out to build credibility with the indie-friendly crowd, of both retailers and readers. After all, no amount of marketing is as effective as pure word of mouth.

And that’s all we ask from readers, really — if you’re enjoying an indie book, *tell people*. Tell your friends, tell your retailer, tell your librarian, lend the trade to your friends, whatever.

It may seem like a small thing, but when hundreds or even thousands of people all do that small thing, it becomes huge. And that can mean the difference between life and cancellation.

Continued belowBrandon Montclare (Rocket Girl)

For print sales, when do you feel the financial impact of a single issue, say, the most recent #5? Is that something that hits after orders have closed, after release, or some other time?

BM: This is actually a more complicated question than one might think. The easy answer is Reed and I get “paid” from the single issues two months after the in-store date. Image collects the money from Diamond and forwards it to us (minus print expenses and their flat publisher’s fee). Rocket Girl #5 was in-stores 5/21, and we expect to be paid for that issue at the end of July. That July report from Image will pay us for all the number #5s sold to stores in the month of May. Any reorders after May get paid with a whole bunch of other stuff (reorders on other issues, digital, &c) twice per year (December and June).

Working backwards a bit, for Rocket Girl #5 I knew on May 1st how much I’d be paid on July 31. May books are solicited in March Previews, and Image needs the cover Image and solicitation copy in February to prepare it for Previews.

This winding answer, I hope, sheds some light on the importance of cash flow. Amy and I are committed to an ongoing series. Books planned for release don’t see a return of single issue sales (which to be clear is the first source of revenue we collect) for 6 months. But once you get over the early hump of starting a new series, you can take advantage of cash flow. That July check, technically, is for February work already done. Buy practically speaking, it’s paying Reed and me for the work we’re doing now (which fans will see in September). Stack this all in a row like dominoes, month after month, and it’s a crude model of cash flow. And the continuing support of single issues shipping periodically and creating a pay stream is the backbone of supporting Rocket Girl.

There are a ton of nuances, but one important note is Image’s role in cash flow. Diamond has to get paid to print Previews and collect pre-orders. The printer needs to get paid. Image staff who do things like advance publicity and pre-press and everything else needs to be paid. Image fronts all of these costs, and doesn’t collect any return on a single issue until almost the exact same time the creators do.

You mentioned digital sales in your comment, but not as something that hits on a monthly basis. How do digital sales come into you and Amy for Rocket Girl? Is that part of a royalty check you receive every quarter or half year instead of monthly?

BM: You get paid for some of the digital sales with the check mentioned above. But I think these are only sales for what Image sells directly (and DRM-Free!). The other stuff gets paid twice per year. That’s down to when Image actually collects the money. It’s a long process getting the reports from Comixology or iTunes or whatever else. Digital sales or Rocket Girl are still comparatively low–and since I can’t project that income, I try to treat it as an unexpected bonus when it does come in.

With such a fine line deciding success, what was your approach to promoting Rocket Girl? As part of that, how much retailer outreach did you do to promote the book?

BM: I’m more familiar with the Direct Market than most–certainly creators, but also more familiar than 90% of the people who work on the publisher side of things. I bought into a store when I was still a teenager and was a full-time retailer and a somewhat big store for a long time. I hope it comes as an advantage, but comics shop owners tend to be independent spirits–and one size doesn’t fit all. Direct Market is certainly the best channel, because single issues are of primary importance, so it gets most of our attention. We’ve reached out directly to remind them of order cutoff dates, sent signed posters for their pull list customers who get Rocket Girl, and try to let them know we’d love to listen and help them sell our book. The retail market is top heavy–I’m sure the top 20% of stores sell 80% of all comics. And that becomes more true the more independent (ie: away from Marvel/DC) you get. So practically speaking we try to focus on the stores where sales are strong. It’s easier to convince a store that sold out of 30 copies to up it 33% to 40. Not so easy convincing a store that sold out of 5 to up it 200% to 15–but the net to us is the same. That being said, I’m happy to talk any retailers ear off to just get them to get one more copy!

Continued belowWe started Rocket Girl as a Kickstarter–which is direct to fans. To be honest, it is demonstrably true that most–especially most larger volume–stores supported the idea of Kickstarter. There’s some thought that it’s competitive, but that’s simply not the case. The Kickstarter supports were vocal, and told their friends to buy the book. Plus they all go to the shop to get new issues.

The difference of 4,000 copies being sold or not is the difference between making Hulk or Batwoman money for you and Amy or wrapping things up, but that made me wonder: when it comes to financials, how do you establish the break even line? Beyond that, going into the project, did you give yourself a certain length of time to keep at it before moving on from the project if it didn’t reach an audience big enough for it to be financially viable?

BM: Going in, we had an exit strategy that got us to issue 5. We felt we could cover that with the success of the Kickstarter and Image launch, even if all other things failed. By the time we saw the Initial Orders on #2 and #3, we knew that we could go to at least 10.

Every creative team has different needs. At 12,000 copies we can pay ourselves 100% of our Big Two rate with the profits of single issue sales plus an extremely conservative estimate of what we’ll make on digital, collected editions, merchandise, convention sales &c. Slightly less sales means we need slightly better revenue coming from everything that’s not single issues. And so forth. In all honesty, our line (I wouldn’t call it “break even”–but the amount where we’re viable) is determine by Reed. I can work on several projects. Pencils, inks, colors, letters are a full time job for her. Plus publicity and design and all the other efforts she puts in. For her, she needed to make 67% of her DC exclusive rate. To be honest, I think every single Marvel or DC creator would leave the Big Two characters if they knew they could make 67% of their rate plus own their creations. We made it happen. And we have been successful enough already that we can project making 100% of our Marvel/DC rates through issue 10. Whether we can maintain that with a numbers 11+ remains to be seen. But as with the first arc, and with the discussion of cash flow above, our analysis of whether we can do #11 needs to start well before we get the paying results of #10. It’s not right now… but it’s coming. The results of single issue sales on especially #6, but also #7 and #8 will start to determine the future of the next arc.

BM: We won’t know the all of the initial numbers on Rocket Girl Vol 1 tpb for about a week. Image told us to expect total initial orders between 3000 and 10,000 copies–so it’s a pretty wide swing. Orders from Diamond for the direct market (comic shops) are already well over 3000, but not so much over that we’ll necessarily pass 10,000 when the mass market (book store, Amazon) numbers are in. You have to note: mass market sales are returnable. Countering the negative of returnability in the grand scheme of things: ia collected edition is going to have more legs than a single issue–ie: it will sell consistently as a reordered backlist item. So it’s just too hard to accurately predict. The best you can do is project based on the past performance of similar titles. I should also note that Rocket Girl Vol 1 is incentive priced at $9.99. So the margin isn’t as high as it should be. It’s a sure thing that the initial shipment of the tpb (which collects 1-5), won’t generate 50% of the revenue that 1-5 did combined as single issues. Again, countering that is the fact that production costs (really, the creators’ time to make the book) isn’t even 5% of what it took to create the original issues. It’s just a reprint of work already done and paid for.

Continued belowOf course, if you have a book like Watchmen where popularity endures, or Fables that has grown its fandom through collected editions, or Walking Dead that does both–collected editions can surpass single issues in the long run. And this conversation that has sprouted up–it’s not to say that a fan who buys a single issue is more important than the fans who waits for the trade (or waits for the movie). The almighty dollar is at the very least a good equalizer. Single issues are where you usually make the most money as well as where you usually first make it. It’s the most important channel. A creator-owned publishing strategy should recognize it. But the end of the day: we don’t want people buying single issues of Rocket Girl out of charity or a sense of patronage. We want people buying the singles because the story is so good they can’t-wait-for-the-trade. If a creator can make something that does that, everybody wins.

You probably had a longer lead time with the Kickstarter and everything, but how long were you and Amy focusing on this as your main project before the first check arrived for a monthly issue?

BM: We first started thinking about Rocket Girl right after the publication of Halloween Eve… so late in 2012. I think Amy had some other short projects early on (as opposed to now, where Rocket Girl is full time). But by the time we launched the Kickstarter (which is a full time job in itself!), Rocket Girl was already her full time gig.

Frank Barbiere (Five Ghosts)

For your creator-owned projects, how important are sales of the title as a monthly in terms of your book continuing forward as a project? Does the prospect of digital or trade sales change how you view success at all, or up front, is it still mostly dependent on those single issue sales?

FB: This is a point I will be revisiting continuously throughout this interview–while sales are “important,” they’re not what allow us to continue doing the book. We continue doing the book, as do many of our peers who do creator owned work, because we want to. Comics, particularly “independent” comics, is not the best “business.” Even when you are selling around 8-10K a month in floppies, that’s not a huge amount of money coming in. It’s “sustainable,” yes, but there has to be compromise all around and an understanding that there are no financial guarantees.

Digital is still evolving. We really don’t make much from it, and while it’s great to have, it’s not as vital to our book as it is to some others. Trades have been wonderful and certainly pick up a lot of slack for issues, but even still those payments don’t come in regularly and can hardly be used to “live off of.”

I’m not trying to make myself out as some kind of comics messiah here, but the only thing I want to be doing is making comics. I’ve managed to transition to a full time writer because truly the only thing I care about is making comics. I don’t go on fancy vacations. I don’t go to the bar every night. I don’t buy super nice stuff and live in luxury. I know what I want to be doing and I work my budgets around making comics—it’s how I’m able to do Five Ghosts, and frankly, that’s all I care about. I’m not telling other creators they have to do this, I,m just saying it’s how I can afford to do it even when we aren’t selling thousands upon thousands of comics. My collaborators on the book are the same—this isn’t a luxury or gift. We do this book because we can’t imagine a world where we’re not working on this book (or on comics in general).

Continued belowFor print sales, when do you feel the financial impact of a single issue? Is that something that hits after orders have closed, after release, or some other time?

FB: You know what you sold well before the issue is on sale. I don’t want to go into how particular publishers pay, but in the case of Image there is nothing upfront and you are paid what you earn after an issue is released. Using “dirty math” it is possible to predict what an issue will net, but things like the fluctuating price of paper and freight (shipping) can change that. There is no guarantee at all, but you can get a ballpark. As soon as the FOC numbers come in we’ll be aware what we’ll be dealing with, but we’re still all being paid off the backend so it doesn’t change the fact we’ve already done the work.

Jim Zub actually has a fantastic analysis of how this all breaks down over on his blog.

With such a fine line deciding success, what is your approach to promoting a new book you’re working on? As part of that, how much retailer outreach do you do to promote a book?

FB: On the business side of things, retailers are the single most important people involved. As many of us know, comics are mostly non-returnable so retailers take a huge risk when buying a book—they are basically ordering something that they can’t return, so their only way to make a profit is to sell it to an actual customer. I make it a priority to have really good communication and contact with the retail community—they are the ones who are on the ground floor and know the customer base better than anyone. I think as a creator, and especially new creator, you need to put in the time and get to know these fine folks. They’re all hugely into comics and want to find cool books for their stores—it’s myopic and ignorant to leave it all to them or your publisher’s PR department to sell your book. You have to be active and involved, you need to keep them updated, and you have to hit the pavement.

The creator (who I keep referring to as “YOU”) also has to be realistic. It’s very easy to want to “blame” retailers for your book not selling more—I constantly hear woes about why retailers won’t buy more of a book, etc. This is…ridiculous. How can you be made at someone for not buying something they CAN’T SELL. If fans were coming into a store in DROVES demanding your comic, the retailer would be buying it by the thousand. Yes, the distribution system has its quirks and nuances, but as a creator you should NEVER blame a retailer—it’s your job to create a good product and to promote it, to drive excitement, and get people into stores. You can’t force someone to try to sell something that has no traction; it’s impossible. This is why it’s important to stay in touch, to understand the market, and to most obviously be realistic. You can read sales estimates every month at icv2.com and comichron.com. You need to understand what books actually sell, how “hype” and “speculation” affect early sales, and many other factors before you start pointing fingers. Also: there are really not a lot of readers. How many people do you know off hand who go to the store every Wednesday? You feel that bite when you ship books in the direct market and you need to plan accordingly.

In summation: retailers are a vital part of this community, are HUMAN BEINGS who should be treated with respect, and you need to be honest with yourself and educated about the industry if you want to succeed.

FB: Again, it’s a bit of a different position for me as I’m a newer creator, but simply by putting something out into the Direct Market through a publisher you know you’re guaranteed a certain amount of sales. Yes, you have your numbers you’d like to hit, etc., but for me I still plan my projects by what projects I’d rather do than what I think will sell. If I want to do a 10 issue series that won’t sell, I’ll figure out how to do it—I think it’s important, while being realistic, to not let the market drive what you create. You have to find a way.

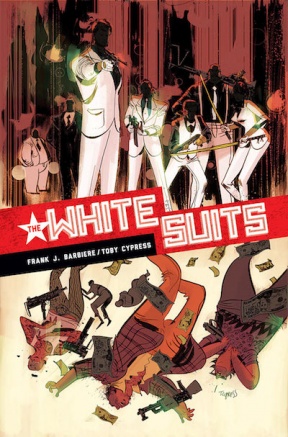

Continued belowCase in point: White Suits sold 1/4 as much as Five Ghosts did. Does that make me regret doing the project? Would I have not done it if I knew this? No. This was a project I”m passionate about and I knew might have a niche audience. Would I do more unique creator owned books that don’t have as big of an audience? Absolutely. But it’s up to me to deal with those decisions, on how to finance the book, and work out the logistics. You can’t come into this business with the mindset that your publisher will sell comics for you. It just doesn’t work that way.

When it comes to your artistic partners on a project, because of the extended wait for payback on creator-owned books, do you look to offer your collaborators page rates? Or does it depend on the situation?

FB: This is “the question.” The answer varies from person to person, as it varies from project to project. As a creator I’ve always believed in paying collaborators up front—especially for “pitches” (5-8 page proposals)—but the reality of this is that you really have to assess it on a project by project basis. What follows are a lot of my specific views, but they work for me.

Firstly, all of my collaborators on creator owned books are partners in the material. Writers need to get off the high horse of thinking they own something completely because they “thought” of it—there’s a human being drawing this, there’s a human being coloring this, and it would not be the product you see in front of you without them. It’s not just yours.

On payment: yes, for any proposal or directly for hire work I will do my damnedest to pay out at a good rate…you can’t expect people to work for free. But this goes both ways: if you are an artist and asking writers for $300 a page…you need to check yourself. Here is the honest math on that figure—if you want $300 a page (just for pencils and inks) that means we are going to be at a budget of $6,600 an issue JUST FOR YOUR PENCILS AND INKS. While I won’t get into the total math, at $3.50 that means you would need to sell around at least NINE THOUSAND COPIES JUST TO PAY YOU (before people crucify me for that figure, it’s a rough estimate and pretty backed up by numbers I know to be true). If you are an artist who can sell that many books on merit of your own name, awesome—let’s do it! However, if you look at any sales number, that is not an honest number. And that’s with a deal where no backend is allotted to publisher, etc. That’s basically only Image, by the way. This is why people need to understand when they work on creator owned material they are GAMBLING. Yes, you should be paid for your time, but it’s very, very, very, very, very difficult to put a hard number on that. You get paid what you earn, not what you think you’re worth. And quite frankly? If you can’t deal with that, you shouldn’t be trying to work in creator owned comics.

You have to be prepared to know that it is very hard to turn a profit and even when you have a book that sells you could end up only making $200 for a month of work. It’s how it goes.

Here is the trade off: as a writer on a book, unless you are in fact the one driving these sales (and even then), YOU DO NOT GET PAID UNTIL YOU PAY YOUR ART STAFF. PERIOD. If you are taking a cut of profit before the art team, you are a fucking asshole. That’s not how comics work. While I don’t believe people can put a price tag on their time, as a writer you have to, HAVE TO, understand it literally takes longer to draw than it does for you to write. It is much easier to have a day job and write than it is to pencil, ink, or color 22 pages a month. It is disingenuous to everyone involved if you are taking a cent from the art staff before you manage to pay them a fair wage.

Continued belowOnce you’re in the green and everyone is paid up, that’s when you start splitting profit. Yes, that makes it very hard to make money as a writer from creator owned material. But ask anyone who’s been making comics for a long time, and it’s how it goes.

Five Ghosts has been a success, especially considering how new you and Chris were to comics, as it expanded from a mini to an ongoing after a strong start. To you, what do you think the key to your success was in finding an audience for your book?

FB: Thank you for the praise. I think we make a very honest book we enjoy, and we’re happy that it resonates with readers. Chris, Lauren, and I love this book and put everything we can into it—and we certainly don’t feel owed anything or expect people to love it. Every reader we have is really a gift and we couldn’t be more thankful. That being said, we are committed to at least 25 issues (and hopefully many more) as we have a specific vision for the series we want to deliver on. We can always use more monthly readers and will be pushing the hell out of our new arc starting at issue 13, but it’s very simple at the end of the day—you can’t make people like something. I don’t want to be the guy trying to stuff my comics down your throat—I’ll make them whether they sell or not and will never compromise my vision for sales. If we can meet in the middle and find material that sells while I stay true to myself (as well as my collaborators), well—that’s a nice world!

Jay Faerber (Copperhead, Near Death)

For your creator-owned projects, how important are sales of the title as a monthly in terms of your book continuing forward as a project? Does the prospect of digital or trade sales change how you view success at all, or up front is it still mostly dependent on those single issue sales?

JF: That’s a good question. The last time I launched a creator-owned series was back in October 2012, POINT OF IMPACT from Image Comics. I’ve got a new book coming out in September from them called COPPERHEAD. So that’s nearly a two-year gap. Image has seen a LOT of growth in that time, with more and more high-profile creators coming to Image, and much stronger launches across the board.

For print sales, when do you feel the financial impact of a single issue? Is that something that hits after orders have closed, after release, or some other time?

JF: Well, the primary way we feel a financial impact is when we get the actual check from Image, and that happens after the book is out. But we get a sense of what that check is going to be when we get our initial orders. That’s a couple months before the book comes out. Then there’s “Final Order Cut-Off,” which lets retailers adjust their orders up or down much closer to the release date — about 20 days before shipping, I think. So that’s another important milestone to gauge just how much money we’re gonna make. Then, of course, if the book sells out (like a lot of Image debut issues seem to do these days), there’s the question of whether you go back and do a second printing, which is another determining factor in the book’s financial success.

With such a fine line deciding success, what is your approach to promoting a new book you’re working on? As part of that, how much retailer outreach do you do to promote a book?

JF: Up until now, I used to be a “build it and they will come” kind of guy. I wanted to focus on putting out the best book I could, with the hopes that it would find its audience. I’d do the usual round of interviews on the various comic book websites, but that’s about it.

Continued belowBut with COPPERHEAD, and the other new series I’ve got waiting in the wings, I’m making a much more concerted effort to reach out to retailers. If I could change one thing about my previous creator-owned work, it would be that. I should’ve done a lot more retailer outreach.

The day after we announced COPPERHEAD I personally emailed over 100 retailers, giving them a PDF of the complete first issue, plus offering to do store signings and exclusive variant covers. Basically whatever I could to help them sell the book. We’re in this together.

I should point out that my failure to do this in the past isn’t that I didn’t appreciate retailers, it was more that I’m an introvert. I’m much happier at my desk writing than putting on my salesman hat and shilling my book, whether it’s in person or on the phone. But I’ve come around just how unavoidably important it is to go the extra mile when trying to launch a new creator-owned book.

When you go into a project, do you go in with the idea that if you don’t hit x level in sales by y amount of issues, you’ll have to reassess the viability of the project? How much are those elements on your mind when you go into a new book?

I don’t think of it in concrete terms like that, no. I usually go in with a minimum commitment with everyone involved. We all agree to do x number of issues, regardless of how well the book does. If we can’t sustain it past that number, we wrap it up and move on. But we’ll do that number, regardless. It’s at least six issues, but usually closer to twelve. You wanna give the book time to find its audience.

When it comes to your artistic partners on a project, because of the extended wait for payback on creator-owned books, do you look to offer your collaborators page rates? Or does it depend on the situation?

JF: If possible, sure, I like to offer page rates. When I launched NOBLE CAUSES way back when, I owned that book completely. Everyone else who worked on it was work-for-hire. Therefore, they all got page rates. I was a bit naive at the outset, and set the page rates way too high and ended up having to renegotiate when we saw where the book was leveling off in terms of sales. But I always worked in good faith with everyone and was fortunate to work with people who were understanding and willing to make sacrifices for the book.

Since then, I’ve always co-owned my books with the artist. Sometimes I’ve been able to offer an “advance,” but it’s always against their share of the profits. Ultimately, each book is different, with a different deal in place.

In creator-owned, you’ve seen a bit of everything with your projects like Dynamo 5, Near Death and Noble Causes. From your experience, what are the biggest takeaways you have about achieving success in creator-owned, and how are you going to carry that into a project like Copperhead?

JF: It’s often been said that creator-owned comics are a marathon, not a sprint. You’ve gotta take the long view of success. Because even if a book launches high, most books see a fairly steep drop-off over the first year. So no one should be quitting their day job when those first issue order numbers come in.

But I really feel like Image is in a much different place than it was just a few years ago. They have so many more high-profile creators, so Image’s profile as a company has risen. People are paying a lot more attention to Image books these days, and I’m really curious to see just where COPPERHEAD launches, given all that.

Jim Zub (Skullkickers, Wayward)

For your creator-owned projects, how important are sales of the title as a monthly in terms of your book continuing forward as a project? Does the prospect of digital or trade sales change how you view success at all, or up front is it still mostly dependent on those single issue sales?

JZ: Every project is a bit different, so it’s hard to give a one-size-fits-all answer for that. In the case of Skullkickers we’ve been able to keep the series rolling thanks to strong digital and trade sales, but it does mean I have to pinch every penny on it and float the expenses for months before the money is anywhere close to evening out.

Continued below

With Wayward arriving in August it’s a whole different ballgame. I’m able to take everything I’ve learned creating and promoting Skullkickers and leverage that to convince retailers and readers that they want to get in on the ground floor of an exciting new series. The response so far to the announcement and press has been really strong so I’m cautiously optimistic.

For print sales, when do you feel the financial impact of a single issue? Is that something that hits after orders have closed, after release, or some other time?

JZ: With creator-owned it’s a serious uphill battle right from the start. You have to get professional material together for a pitch and then, if it’s picked up you have the solicit cycle, actual creative production, printing, distribution, pay arriving from the distributor, and then, finally, pay arriving to the creative team (if there’s any money to be had). All told you’re looking at anywhere from 6-9 months for that first paycheck. That’s half a year or more where everyone on the team has to keep the lights on and food in their belly while waiting to see the financial fruits of their labour. There’s no way that won’t have a heavy impact at every stage of production. I know every creator says it, but a regular shipping creator-owned book is an intense creative and financial commitment.

With such a fine line deciding success, what is your approach to promoting a new book you’re working on? As part of that, how much retailer outreach do you do to promote a book?

JZ: I’m a pretty relentless promoter and do everything I can to convince people my books are worth picking up. If I’m not dedicated and enthusiastic about it I don’t see why retailers, the frontline people putting up money for non-returnable product on their shelves, should be.

I have my own mailing lists for fellow professionals, retailers, and press outlets and try to communicate with all three of those groups as best I can to get the word out about new projects. It’s a media-saturated world and independent comics compete for shelf space with worldwide brands from Disney, Warner Bros. and a host of others so I try to use everything at my disposal to stay visible. If a creator-owned project I’m doing fails I don’t want to have regrets wondering if I could’ve done a better job promoting it.

When you go into a project, do you go in with the idea that if you don’t hit x level in sales by y amount of issues, you’ll have to reassess the viability of the project? How much are those elements on your mind when you go into a new book?

JZ: I’m a storyteller first and foremost so I try not to make production into a math formula, but you can’t help but feel the hard reality if those numbers end up working against you, sure. I’m here to tell stories that mean something to me but I also need it to be financially viable over a longer period. I’m learning more and more of the business/financial side of it and have thresholds in mind, especially now that I’ve experienced some of the roller coaster ride of running a creator-owned series for the past 4 years. You have to balance the creativity and the business sides of the whole thing.

Like any creative endeavor there’s a lot of adrenaline and fear wrapped up in the whole thing. The day we announced Wayward publicly I could barely sleep as those numbers kept crashing into my brain. It can be pretty nerve-wracking at times but I do my best to keep plugging away.

When it comes to your artistic partners on a project, because of the extended wait for payback on creator-owned books, do you look to offer your collaborators page rates? Or does it depend on the situation?

Continued belowJZ: I pay the Skullkickers art team a page rate (and wish I could pay them what they’re worth). That’s been the deal since the start. I take on the financial burden of the series and captain the S.S. Skullkickers each issue. Sometimes we take on water, but all in all we keep the whole thing afloat.

Wayward is different in that Steve and I are co-creators on the series. It obviously takes him a hell of a lot longer to draw the series than for me to write it so there are allowances for that, but we’re both sacrificing a lot to see it come to life… Just ask our families. 🙂

Each creator-owned project has its own needs and I think it’s wise to approach each one as its own thing.

JZ: Skullkickers was absolutely a learning experience and it informs everything else I’m doing.

The two biggest changes have been building my skills and expanding my network of readers, retailers, and industry friends. Both areas are crucial and, unfortunately, they both require time to mature. I don’t think there are many shortcuts to that kind of growth. You need to keep building things to get better at it and you have to be seen and be consistent over a long period for that network to expand to a point where it’s really benefiting you.