“Savage Town” is the irresistible upcoming graphic novel scripted by Declan Shalvey. The artist of “Injection” and celebrated runs with “Moon Knight” and Nick Fury sat down with us to discuss his writing turn with artist Philip Barrett on the new self-contained OGN from Image Comics, due out in September 2017. “Savage Town” combines the best of crime and gangster tales, character-based graphic novels, and the distinctive voice of Limerick, Ireland, into a fresh, funny, and unflinchingly real story.

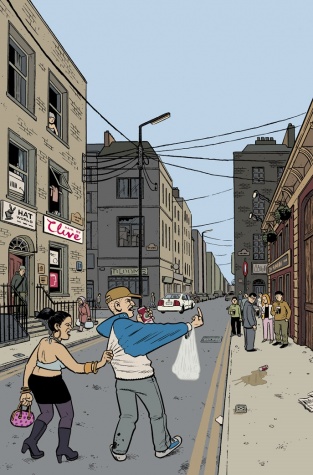

Shalvey has long been a champion of giving artists their due credit. So “Savage Town” lets Philip Barrett, a longstanding Irish cartoonist heretofore less known in the US, show off his wry, distinctive, and charmingly proletarian cartooning chops. Shalvey’s Red Cube Studio mate Jordie Bellaire’s colors give the Limerick landscape just the right pitch of brick-and-pavement dusks and musky tracksuit atmospherics. And Clayton Cowles’s letters convey the loose tongues and quick banter that Shalvey populates the pages with.

But just as delightful as discovering Philip Barrett’s art is finding Declan Shalvey to be a colorful storyteller and stylist with dialogue. We love what we have seen of “Savage Town,” so we are glad to bring you this conversation with Declan, here excerpted from the full conversation that you can hear next Tuesday (8/8/17) on the Comics Syllabus podcast here at Multiversity.

Meanwhile, enjoy this interview with Declan Shalvey! SAVAGE TOWN comes out September 20, 2017 from Image Comics. You can pre-order “Savage Town” from your comics retailer with Diamond ID JUN170700.

We’re talking today about SAVAGE TOWN, your original graphic novel with Philip Barrett on art, Jordie Bellaire on colors, and Clayton Cowles on letters. Right off, I want to ask you about the word “savage.”

Declan Shalvey: I’m from Ireland, from the West side of the country– I live in Dublin now, which is on the East, but Ennis is my hometown, and I lived in Limerick for a few years. In Ireland and especially in that area, “savage” does mean something quite horrific and whatnot, but we have a weird way of making bad words something good depending on how you say them. So if I say, “that was a savage attack,” of course you know what that means. But if I said that was a “saaaavage” attack, it’s probably like a kung fu film or something that was really cool, you know? The more you elongate the “savage,” the better it is, you know?

It’s kind of becoming a running joke because I’ll talk about the book, SAVAGE TOWN, and then I’ll say how something is “savage,” and I’ll realize I’m using the word so much, it’s like the best marketing strategy you could ever think of, you’ll never forget the name.

But seemed like such a perfect way to…. I have a love/hate thing with Ireland, you know. I think maybe everyone has that with the country they’re from. But there’s so much I would be critical about, and there’s so much I just love. And I think the word is just a great way of addressing the fact that there’s really, really good things, and there’s really, really bad things. And sometimes they’re both the same thing.

Yeah, we do that with language. Growing up in the 80’s and 90’s, we would always turn the negative words into positive, like “bad” or “wicked.”

DS: I quite like that. It’s also kind of why I’m doing the dialogue the way I am in the book. I’m interested in the turn of phrase. We have a different accent here and the way we use language is very different. I used to live in New York for a while and I use to keep having these cultural tricks where the way I say something– in Ireland, you pick up on the pattern of speech and you get the intention, but to take it literally, it’s nonsensical. So that’s something I thought was interesting, and thought it’d be cool to play around with it, you know?

It’s there in the title, and there’s a scene early in the book where a man is driving by in a car and sees an attractive woman and he calls her “savage,” and I thought that was a nice reference to the way the word works in different ways in your book.

Continued below

DS: Yeah, it’s a balancing act: I’m aware that this is going to be to a large American audience. But at the same time I didn’t want to have to simplify it.

The Wire is actually a big influence on the book — not that it’s nearly as sophisticated- – but in that what I loved about The Wire was that it was very hard to follow at first, because it was all the street speak, and it was the cop lingo. Both were just as inaccessible as the other, but after you watch it for a while, you kind of get into the world.

And I think the advantage of “Savage Town” being a graphic novel is, you can lose someone in 20 pages if you stop reading, but if you got 100 or so pages, you’ll acclimate to the world as such. I wanted to make sure I wasn’t giving the Diet Pepsi version of it. But at the same time, I couldn’t go 100%. I think there’s a line at the first page, where there’d be lingo I would use for drugs, but I feel like I’d lose you on the first page if I used that lingo, you needed to know it was drugs. Tiny little things like that. Things like slowly ingratiating those phrases, and by the time you’re in there, just totally go full in.

I don’t consider myself a particularly wordy writer. I hate wordy comics. But I did very much want the dialogue to be definitely informing the world. There’s even a scene later on when someone from England comes in, and I wanted that to be jarring. So somebody comes in speaking “proper” English, and the reader would be jarred by that, the way that I would be jarred by that if someone with a different accent came in, you know? It’s little things like that I wanted to play around with.

It’s rich, and richly “of” that place. Let’s give folks a picture of what “Savage Town” is about. What is the premise of the story? We know it’s a crime story, set in Limerick. Why was this a story that you wanted to tell?

DS: The barebones of the story is about Jimmy Savage who’s a small-town criminal in Limerick City. There are two big gangs, he’s not part of either of those gangs. He basically lives in the margins and just gets to make a living and he’s fine. As the story develops, things get messier and Jimmy can’t live in the balance as such, and he will have conflicts and hilarious situations will arise. To be honest, the story is shite. It’s not the most compelling plot.

[Laughter]

DS: Basically, the crime story is kind of the skeleton in which to play around with these characters. I wanted to do an Irish story. I’ve worked in American comics for many years now. One of the characters in “Injection” is Irish, and it was so satisfying to draw Dublin in a panel. And just to see that… I remember when I was a kid and I would see Garth Ennis have a scene set in Dublin… I love that stuff!

But I didn’t want to shoehorn it in to superhero comics. And having done “Injection” with Warren [Ellis] at Image Comics has been a hugely empowering experience, where I can do the work that I care about. And I can make it look exactly the way I want. And it can be a success and I can make a living on it like I did in superhero comics.

And I don’t know if you’re familiar with Roddy Doyle, he’s a writer. There’s been some films based on his books like The Commitments. His The Snapper was the main inspiration for the book. Like, that’s how I remember my childhood: Blatant disregard for your children’s lives. If the dog bit you, “ah, he’ll be fine.” The irreverence of it, I really responded to. And I remember thinking, I’d love to see that in a comic. Closest thing you could do is maybe Garth Ennis, but Garth’s work is more horror-based, or goes off in different areas like that. I really wanted to tell a grounded story.

Continued belowJust to unpack the crime aspect: What is it about crime stories that make them so good at opening up a glimpse into certain things? Like if you want to tell a story about a place, whether it’s Baltimore in The Wire, or whatever sub-culture that’s in The Godfather or a Scorcese film, what is it about crime that lets you do that so well?

DS: That’s a good question. I remember I listened to a panel about crime comics with [Ed] Brubaker and some other creators. And it was something I hadn’t considered before, something I always attributed to science fiction, that for me science fiction is best when it’s telling a story about NOW, but you don’t know it. Star Trek, Children of Men… you’re telling a story about tomorrow but it has such relevance today, because it gets you to see past race or class or whatever.

Even 28 Days Later.

DS: Yeah, absolutely. I’m not a horror film fan, but I saw it as Sci-Fi. I did a book based on 28 Days Later and that was my way into the story, basically, [like] it was a Sci-Fi tale. And I remember Ed Brubaker saying something along the same lines, in that you can use the genre of crime to tell another story.

And I’ve watched The Wire seventeen times and listened to all the commentaries. And I know exactly what The Wire is for David Simon: it’s a story about America. And even though I knew this, hearing Brubaker explain this in those very basic terms, I’m like, “yeah, it’s just another way to tell a story.”

It’s not like once you make something crime it’s inevitably cool. But you know, there’s all these cool visuals: guns are cool to draw. I love shadows. And anti-heroes. And people being forced into a box and to react in different ways. You know, it’s different than a straight drama.

Crime has the ability to show everyday life and a real solid sense of place, but very heightened. The tension is tighter. And it makes room for the wit and interaction that you pull off so well with your dialogue and character building.

But I also want to give you a shot to talk about artist Philip Barrett, who I think is a revelation here. What was the impetus for you collaborating with him?

DS: Well I’ll be honest, part of the reason for me to do this book was basically to create a portfolio for Philip Barrett. I met him years ago a small comics faire in the UK. He’s an illustrator by trade, and he does his own comics in his own time. He’s somebody who, the artistry is first and foremost. And I just got so pissed off waiting to see a body of work by Phil that was just a whole story. He’s done loads of short stories in collections and stuff, and I mean, they’re all great. But I just wanted… a BOOK, that I could read, sit down, and read a story all drawn by Phil, just what Phil does. I wanted it to exist, and I saw a way in which we could make that happen.

Because he’s just… he’s Ireland’s secret weapon. He’s an amazing storyteller. He’s done these short stories, like one about some kids at a bus stop… [the work] just feels so Irish, you know? Even though it’s cartooned–Phil doesn’t draw super realistic, but there’s a charm to his line and his characters. But I feel like you know when he draws a dog on a leash on a path, it feels like what I’ve seen outside my door.

And especially now, seeing what he’s done in “Savage Town”… like in the pub, there’s all these pots above the door? And I remember being a kid when they had those. And the way he draws the estates, all the cars in the driveways, and the old gates… He just has this great information bank of tiny details that make an environment real. A lot of Image books are really about identity, like “Southern Bastards” is about the South. And I felt like if I was going to do this, if I wasn’t going to draw it, it had to be the most “Irish” feeling book that it could be. Any other artist wouldn’t have done half the things Phil has done. And half those things Phil has done, you wouldn’t even notice, but it just contributes to you feeling like you’re in this environment. Like we were talking about the dialogue and whatnot. Which I think is a really huge part of the experience of reading the book.

Continued below

He drew characters, you know, and just the face on them, I was like, “oh man.” There’s characters in the book that are only in the book because I wrote chapter one, and when I saw the characters he drew, I’m like, “oh, I got to have more of this guy.” Like the two kids in the car? They were, like, incidental, but I saw their faces and I’m like, “oh, there’s got to be more for that guy. I’ve got to bring them back in some fashion.” Because Phil draws– no two characters he draws look the same. They’ve got the terrible haircuts and the terrible jumpers and the tracksuits… it’s such a specific thing, you know? It’s so good.

It’s so good. I love the work. And the book feels organically… you’ve been intentional about giving Phil top credit, which is of a piece with all that you’ve done with #ArtCred. But there’s a tangible feeling that this is a collaborative thing you’ve done together.

DS: This book wouldn’t exist without Phil. But what he’s done has been so instrumental for the book.

When I was working on chapter one, I mentioned some characters to him. Like in the way he draws his own zines, he drew a two-page scene, just to get a feel for the story. And I’m like, “man, this has to go in the book!”

And he’s like, “no no, I was just havin’ a go…”

And I was like, “no, Phil, seriously, I love what you did here!” And I adapted it so it could fit, but that scene is now in the book. And it wouldn’t have been except that he came up with it.

It strikes me that you’re at the forefront of not just current comics’ visual style, but also our recognition of the credit that’s deserved to artist, and how we conceptualize the collaboration. We give credit to artists for their individual work, even when it’s part of a team. But the orchestration of all that creative brilliance, that’s tough. It takes a certain spirit and attitude towards one another that I feel like you’ve been very visible and vocal about. And that’s tremendously good for the field.

DS: Thanks, man.

Whenever I talked about art credit and all that, it was never about me. It was seeing a friend not getting just desserts. And when Jordie wrote a blog post that ended up setting up Colorist’s Appreciation Day, she didn’t get pissed off for herself. She got mistreated by somebody, but it was another colorist getting mistreated that set her off. Me and Jordie are in a nice place where we get hired for what we do, and people like we do. But all the more important that we’re setting up our own [creator-owned] projects.

Seeing how much work Jordie put into a project when she had ownership, you know? Her rates might have been shit, but knowing the feeling like being a part of the team, or feeling that you’re bringing something to the book, that the book isn’t the same without you has been a very empowering experience. And it doesn’t take a whole lot to give that to somebody else.

It’s really crazy, for a mass medium like comics, what it is or has potential to be. The capacity for change is quite massive. And it has changed an awful lot. I would credit a lot of that to Image Comics, because it has empowered a generation of creators. I’m very lucky that Marvel liked me, gave me work. But the best thing you can do as a creator is to empower yourself. And somebody with the creative freedom of Image Comics means that you really can, like they say, be the change that you want to see in the world.

Catch the rest of the interview next Tuesday on the Comics Syllabus podcast, where Declan shares much more about writing crime in Limerick, going from visual storytelling to scripting, working with Jordie Bellaire, creator ownership and collaboration, and how writing is like “doing a poo.” And you can find “Savage Town” from Image Comics when it releases September 20, 2017, or you can preorder with Diamond ID JUN170700.