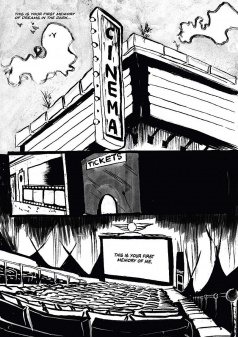

A book that we reviewed last week, Owen Michael Johnson’s “Reel Love” from Dogooder Comics is a charming story about a boy and his theater, done in the wonderfully emotional way that only comics can. A coming of age story a la “Essex County,” the book is Johnson’s first book as both writer and artist, and only goes to further strengthen the connection between cinema and film as mediums that interact with one another.

While the book officially debuts at Glasgow Comic Con at the end of this week (July 5/6) and will be available online soon after, we had the opportunity to sit down and chat about the book, it’s semi-auto-biographic nature and the power of both cinema and comics.

So, I guess the first question I’d like to ask you is: why comics?

Owen Johnson: I’ve never been asked that! Technically, it’s a medium of infinite possibilities and, increasingly in the internet age, open gates. You are limited only by your imagination and the time you’re willing to spend at the drawing board. The community is strong – if stubborn to evolve at times – but most high-level professionals are willing to pass on information to their inheritors. I think this is rare.

9 times out of 10, talent and business acumen are valued over fame and ego.

Other than the pleasure I derive from making them, I love comics for it’s relative youth in comparison to other media. There are oceans of potential directions to take (if those on the ground are willing). Comics are at a very exciting and dangerous point.

Also: money for drawing dinosaurs!

The second, and perhaps fairly “obvious” question you’re prepared for, is: for a story like this, that revolves so heavily around another medium, do you feel comics is the better place to tell the story?

OJ: That’s an interesting question. There’s a lot of similarities. Both are an interaction between word and image (a conceit I’ve always been fascinated with). Both are personal dreams made public. Visual mediums that use sequential images to tell a story.

Crucially, I think the means of production are poles apart. Everyone watches movies. Like comics, they are for the people (or should be). Also, anyone can make a comic if they want to, the materials aren’t expensive. But not everyone can afford to make a professional film. It’s very hard. I know because directors have told me.

The act of hand-crafting images is the joy for me as it releases subconscious intentions. I like having a reader control the pace of consumption available in comics which is impossible in film. To linger over images of interest. Flicking back to seeded information in earlier pages. I like that process and it’s not possible with the cinema experience (although that all changed with it’s possible VHS tapes – which will feature heavily in the second chapter). The control and level of participation a reader is granted with a comic creates an intimacy I’m hopelessly enamored with.

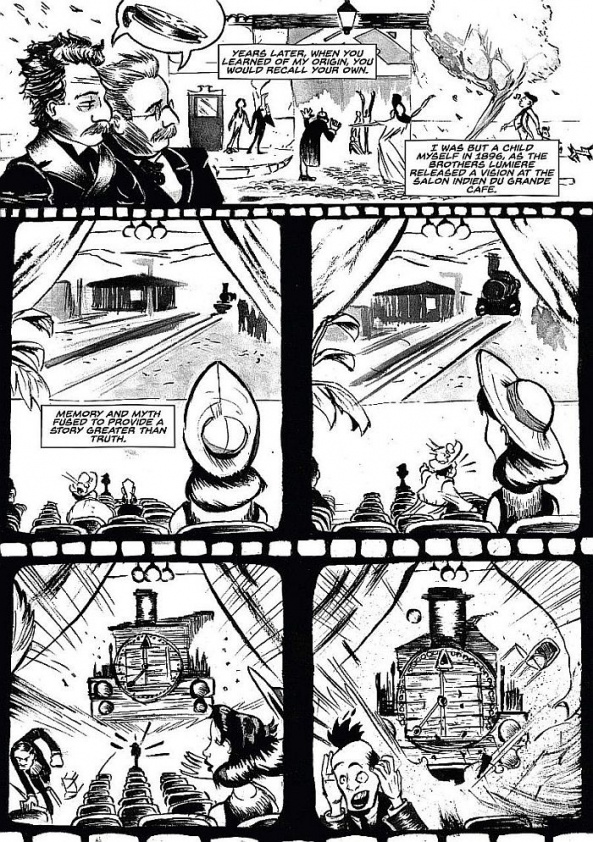

Comics are essential to film. Every movie is storyboarded first. I think its more interesting personally to explore a medium sideways, the examine film through comics. A reader seeing images of a viewer watching images has a special resonance. The film and dialogue is given weight and meaning because of the moments we choose to capture and what that says about the psychology of the character at that time.

Although, to finally answer your question why not make this a film: I’m a complete technophobe – I can’t operate those cursed cameras!

How did you develop your craft? Did you have some kind of formal training, or did you just develop your style on your own?

OJ: I learned many things at school but learning to draw was not one of them. Art classes consisted mainly of typography and making pottery tiki masks. My grandma Margaret and grandad Ernest taught me mainly. They always supplied pencils and paper and entertained my ludicrous daydreams. Any artist who wants to be one will persist, but having someone tell you that you can is essential I think. That and drawing many, many pages of comics.

Continued belowLater on, in working in the UK comics industry, other artists I’ve worked with have taught me a huge amount. Conor Boyle, Mark Penman and the rest of (comic art collective) GHOSTS – I’m sure they’ll all agreed I’d be nothing without their guiding hand!

And how did you get started in comics? Did you read a lot as a kid, or was it something you came to later in life?

OJ: I did read comics voraciously when I was younger. The gateway drug for me (and most children in the UK) was the weekly comic The Beano. My first comic (aged 8) was drawn in the style of The Bash Street Kids. It was about delinquent pirates firing custard pies out of cannons. I peaked. It’ll never get better than that!

My Grandma took me to a library with a bounty of European and Disney comics. Batman The Animated Series was on TV every Saturday morning. That opened me up to American superhero comics and eventually underground comix. Edgier material. But then The Beano was pretty subversive so it all comes around.

I have a couple guesses, but I’m curious — who do you find are your major influences on the series? Whether it be specific artists, books, stories, etc.

OJ: I suppose the biggest influence would be films like Stand By Me, (Brit independent) Son of Rambow. Cinema Paradiso’s shadow looms large. Anything by Edgar Wright who is wonderful at using fantasy, homage and stylistic elements to highlight the cultural preoccupations and emotions of those characters. It was tough research, Matt, watching all these movies, but someone had to do it!

I wanted a balance of direct ‘quick-hit’ references like the two boys quoting movie dialogue to each other. But structurally, and tonally, I made a conscious effort to have the issue ape a specific movement of cinema (in this case 80’s blockbusters begun by Spielberg with Jaws). I wanted the classic Spielberg reaction shots of awe. The magic of suburbia is key in his work so I wanted that to be front and centre. It would have been dishonest and stiff to make a list of movies I wanted to reference and create a comic around that. The movies that get nods are always dictated by the emotional state of the characters and what I felt they were experiencing. That was more important to me.

The earliest artistic influence would be Leo Baxendale. I always begin with a desire to draw sexy, cool characters but they always end up with knobbly knees and rosy cheeks. I think that’s his influence.

I love the romanticism and fluidity of Fabio Moon’s brush. I learned from Frank Quitely the beauty and importance of textural and practical detail, and from Jeff Lemire that conveying emotion should be a cartoonists primary concern. Both fellas have been incredibly generous with their advice and support. Jeff’s Essex County was a revelation that I could draw a comic about where I grew up (the rural North of England), to create something very close to home.

I prefer Jack Kirby as a reader but I believe Will Eisner is a bigger influence on my style. The exaggeration specifically. The invention of his page layouts. The deep understanding of technicality and human expression. I’m a light years behind that level but even a passing glance at The Spirit means I draw a better page immediately afterwards.

To clarify, how much of the story is autobiographical? I mean, reading it I assume this was your childhood, but I suppose I could picking up the wrong signals there.

OJ: If you’re asking whether a ten-foot high naked witch emerged from the screen during Robin Hood? Absolutely.

There are fundamental differences that will become more apparent as the series progresses – and the line between fantasy and reality more difficult to identify. It’s no more autobiographical than anything else I’ve written. Raygun Roads was intensely autobiographical. Even though it was about a cosmic punk band.

But geographically and practically, Reel Love is very explicitly personal. The big confrontation never happened. I have a mother and the main character doesn’t seem to. These were narrative fictions to make for a stronger story. I would always betray gospel truth if it make for a more compelling reading experience. After all, I want to entertain. I intentionally didn’t give the boy a name because he could be any boy, or every boy.

Continued belowMore importantly, it’s a true expression of feeling of that time rather than fact. A major theme of Reel Love is memory, and the part that plays in the movies we make of our lives. It edits in strange ways, with recurring images, stand-out performances, and theatrical villains. As a rule I don’t really enjoy autobiography comics that simply recount events. Memoir by it’s very nature is unreliable. I wanted to heighten and exaggerate the memories. I would never say I set out to do realism. More hyper-realism.

So one thing I notice about Reel Love is how you sort of change your art in order to match certain vibes or aesthetics. How do you find mixing that aspect in, in terms of both staying true to “your style” while evoking specific imagery? (The Sauron reference comes to mind.)

OJ: This is my debut drawing a book, so I think it’s fair to say I’m still finding my style. I was hoping it wouldn’t be jarring to include these disparate film worlds. I was truthful to my perception of how I viewed those movies at that age. Visually, it was important to take creative license because these are fantasies. They’re more imaginative constructs. The Sauron page kind of encapsulates that perfectly as it’s completely subjective. Everything in Reel Love is subjective to that characters mind, how he is viewing the world and experiences these events.

The illustration style will evolve to various degrees with each chapter; dictated by the story and emotional place the character is in. Reel Love #1 is all about fluidity and freedom and looseness. I like the naivety of the line. The next one will be itchier and my technique will have to reflect that because that’s what the story dictates.

The book sort of eschews a lot of “traditional” comic storytelling techniques, which is certainly conducive to the story. How do you find yourself approaching the page? How does the vision come together?

OJ: Colin will tell you it’s frustratingly vague! A tone presents itself before actual scenes or story points. I get recurring images I can’t shake and they go in a notebook along with possible dialogue and character designs. Daydreaming on paper really. Then I break down the structure page by page without being too rigid. I try to fix a rhythm and flow while leaving room to improvise. I attended a talk with Paul Pope recently and he said making comics is like jazz; you have a set structure with movement to deviate and flourish. I think there’s a lot in that.

One thing that stands out is the amount of references the book makes. How do you strike the balance between just the right amount of accessible nods to pop culture versus ones that might be a bit esoteric? Or is that something that’s not even a concern?

OJ: No reference is too esoteric, or off limits, but it’s important they help express rather than overwhelm the story. I really wanted that central relationship to resonate regardless of which movies the reader had seen. Everyone has hung out with a kid more confident and fearless than themself.

The fantasies in Reel Love #1 have a clearly defined beginning and end, but this won’t always be the case. I included movies I felt symbolized that time of life for me, and tried to jettison any doubts about whether they would be lost. You must always create for yourself first, I think.

We do often see a lot of crossover in commentary between comics and film, and a lot of people like to make references in comics to certain collaborators being a “director” or a “screenwriter” or what have you. You touch on this a bit, but why do you think we often look at these two mediums so closely together?

OJ: There are a lot of similarities, although I think too much of that narrows our expectations of what comics can do if we’re constantly comparing them to another medium. I’m interested in anyone who can tell a visual story well, but comics are unique. As a writer/artist you are the actor, director, cinematographer, and editor all in one. It’s a very complete experience to have with a piece of art: it feels like you have total control but if you’re doing your job well, you’re open to what that story tells you it needs to be.

Continued belowI see who I would class as auteur comic artists like Paul Pope, Raphael Grampa, Chris Ware, Charles Burns, Craig Thompson. They are masters at presenting idiosyncratic visions without compromise.

In looking at the future of the book, I do wonder: this issue, “Chapter 1”, is very much stand-alone; you could read this by itself and get a whole story. How are you approaching the overall structure of Reel Love?

OJ: Reel Love as a collection charts a man’s whole life in three parts, in keeping with the three act structure of a film. Each chapter title speaks of the motif of that particular act. Act 1 is Projections. Act 2 is Concessions. Act 3 Admissions. They can be read separately as they each have their own arc, but there is a wider story at work. A regular schedule is intended but I write a lot for other wonderful artists as well as remaining busy outside comics. It’s important to me not to release the next chapter unless it’s ready.

At the bottom line this is an independent book. At 46 pages per issue it takes time to craft to a level myself and Dogooder Comics are satisfied with. We both want to continue this series. There are pages that were cut from Projections as they felt part of book 2. That was a great call from Colin Bell (editor). It’s future depends on people buying it. So everyone should.

Can you talk a bit about what is to come down the line?

OJ: The next issue, in accordance with the rules of a trilogy, is when everything goes to hell in a hand basket. Tonally and practically, it focuses on the video nasties. As the title suggests it’s going to be a little meaner, a little dirtier. If Projections is about falling in love with film as a child, and the honeymoon period, Concessions is about going further down the rabbit hole into obsession as a teenager. I’m upping my intake of Cronenberg, Gilliam, Charles Burns and Robert Crumb.

I know how it’s going to feel to read at this early stage but it’s hazy around the edges. I like working that way. I like to be surprised along the road.

“Reel Love” goes on sale at Glasgow Comic Con this July, and will be available online soon after