Of all the Kickstarters that I’ve personally backed and received, I have to be honest: the Kickstarter for “Basewood” has been the most rewarding. Not only do I just genuinely love the comic that was produced and distributed, but the collected edition of the book is simply gorgeous. Printed in an over-sized European style hardcover, it’s an incredibly gorgeous graphic novel in which you can see just from the cover that a decade’s worth of painstaking work and pride has gone into crafting the interior adventure.

And behind all of it is one man: Alec Longstreth. A self-publishing cartoonist out of California, Longstreth has been self-publishing his own comics through his own imprint/publisher Phase 7, of which he’s reached 18 published issues out of a goal for 100. And with “Basewood” being sent out to backers daily, we decided it was time to sit down and chat with Alec all about his history in self-publishing and his evolution as a cartoonist.

Read on to learn all about the secrets to getting your own comics out in the wild, how to run a successful Kickstarter campaign and when to listen to Dave Sim.

I have a staple question that I like to ask people the first time that I talk to them, and that is: why comics?

Alec Longstreth: Well, for me, I was someone who grew up reading comics. I actually drew a graphic novel about this called “Transition.” And I feel like my path to comics is really similar to others. Soi t’s an auto-biographical story about how I got into comics, and once I drew it, I had a lot of people say to me, “wow, that’s the exact same experience I had.” I almost think of it as a typical thing at this point. I also taught at the Center for Cartoon Studies, and had people tell me “that’s the same path I had.”

So the story goes like this: you start reading comics as a kid, and you’re really into it. For me, it was “Tintin,” Carl Barks, newspaper strips like “Calvin and Hobbes.” Then you turn into an angsty teens and suddenly comics are for kids, you don’t read those, those are stupid. So you lose track in high school or something. In your twenties, you come across a graphic novel or something that reintroduces you to comics. For me it was “Understanding Comics” by Scott McCloud, and you suddenly realize, wow, comics are an amazing art form and not just for kids. And you sort of discover that some of the creative pursuits you’ve been experimenting with like film making would be much better served by drawing comics, since you don’t need a giant budget or a bunch of people to help you. You just need a piece of paper and a pen and you’re off to the races; you can tell any kind of story you want.

So, yeah, when I was about twenty, I read “Understanding Comics” and that was, like, wow. That was what I wanted to spend the rest of my life doing. I am going to make comics forever.

Had you still been illustrating back then, or was “Understanding Comics” what ignited your interest in drawing?

AL: I would say “Bone” was the main comic I had been reading. I turned twenty in 2000, so it was still halfway through the run at that point, so that was the book — but it’s almost embarrassing that, like, now in 2014, looking back on my life? Well, of course I was going to be a cartoonist. I was the kid who was always drawing in class and stuff; in high school, I had these stupid little characters called the Tasgucks, and I used to just sit in the back of the class and I drew about 100 pages of them. Or I’d be drawing comics for the school paper; I went to Oberlin in Ohio and I was drawing comics for that school paper as well.

So it seems, like, of course I was going to be a cartoonist. But it took a while for me to figure that out, and I think “Understanding Comics” sort of pulled the curtain back and was like, hey, look, it’s not just this silly little thing. You can tell dramatic stories, science fiction, whatever. It’s not a genre, it’s a medium. That was the big turning point for me. But, yeah, I was drawing all along.

Continued belowI think your style is incredible refined, and I think you mentioning “Tintin” earlier makes sense as a clear influence, but at what point did you start defining the style you wanted to continue working in?

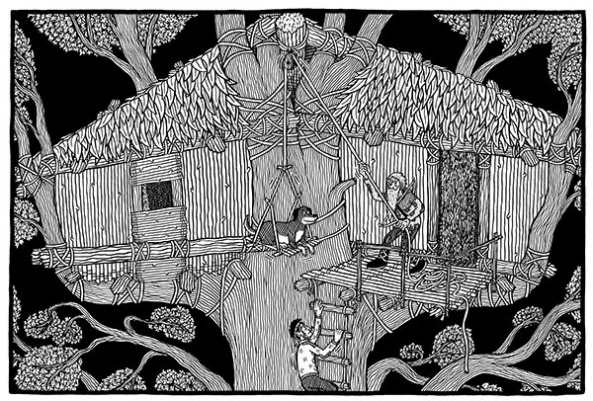

AL: Well, I had the idea for “Basewood” about four years before I started drawing the first chapter. It was serialized in my mini-comics, Phase 7, so the first chapter came out in 2004, but I had started working on the story in 2000. For the Kickstarter backers, I’m compiling the companion volume that’s coming out, that has really early character sketches and you’ll see they’re embarrassingly bad. [Laughs] So when I first had the idea, I thought I’d draw it one way, but I didn’t even really know how to draw.

So, I feel like my style really developed over the first four issues of Phase 7. Are you familiar with Dave Sim and “Cerebus?” He had the self-publishing guide which came out in the early 90’s, and he had said that it’s kind of like that Malcolm Gladwell thing, that a cartoonist needs to draw two-thousand pages, and then they’ll have their style defined. They’ll be a fully-formed master cartoonist or whatever. And, you know, years later Malcolm Gladwell did the 10,000 Hours thing, so if a page of a comic takes five hours to pencil and ink and letter and everything, it works out pretty nicely. I had probably maybe drawn a hundred pages when I started Phase 7, and through the first four issues I’d drawn another hundred, hundred-fifty pages or something. By the time I sat down to draw the first issue of “Basewood,” I had a couple hundred pages under my belt and felt like my style had become pretty established.

It’s just looking at stuff and copying other cartoonists, stuff like that, and then your style emerges.

And how did you get started Phase 7 Comics? I came to “Basewood” because of the Kickstarter, but this is something you’ve been doing for quite a while.

AL: Yeah, Phase 7 started in 2002. So when I graduated from Oberlin, I was still really excited about comics. I mean, I’m still really excited about comics today, but I had a bee in my bonnet about it. I used to publish through the Oberlin Review, which is the main newspaper that comes out every week, so I had a weekly comic that was in that newspaper. There was even, like, an underground newspaper with more street cred called the Oberlin Grape. I used to do a weekly strip for them, too, because I wanted to make comics. And I did a webcomic, and all this different stuff — so there were all these venues for it, but when I graduate from college it’s like, woah. I was going to move to LA, I had almost no friends out there (my friend Andy who is doing the rock opera version of “Basewood”), and I wanted to draw comics but didn’t have a place for them to be seen. So I started Phase 7.

So, there were four issues to start, and then “Basewood” started at issue #5 which took 7 more years to draw. It was sort of a nightmare, but I got it done. And you are holding the results in your hands, I guess!

So obviously we’ll be talking about this with Kickstarter specifically in a bit, but in terms of self-publishing, it’s become kind of hot right now. Kickstarter is a good thing for people trying it out, but you were doing it back when it was much less popular, much more difficult. How did you find the challenges of putting out your own work on your own terms and getting it out to an audience?

AL: I talk about this a lot at the Center for Cartoon Studies where I teach the Professional Practices class, which is sort of all about getting your stuff out there, being a self-starter with comics. You have to be your own promoter and get it out into people’s hands, because otherwise there aren’t a lot of venues, with magazines falling left and right, or weekly papers closing up. There’s not as many venues as there used to be. But I think it’s the kind of thing that anyone can do. It takes a little bit of work and you have to be pretty organized; from the beginning, in my twenties I was very dramatic and a little crazy, so a couple years before I started Phase 7 I made a vow to draw comics every day for the rest of my life. So I’m sitting at my board right now and there’s a big sign that just says “Draw Comics Everyday!”, underlined.

Continued belowWhen I started Phase 7, right off the bat I figured I’d offer subscriptions and that my goal would be to get to issue #100 before I die. Right now I’m working on issues #19 and #20, so I’m a fifth of the way there. [Laughs] But it’s the kind of stuff that, like, I just figured out on my own. But anyone could figure it out, you know? You offer a subscription and people pay for four issues, so you write it down the name and the address and keep track of which issues you send out, and over the years… When I started in 2002 I just had a three-ring binder and I’d put in a sheet for each person and write down their information, and eventually I built a database a couple years later, and now I have about 200 subscribers and can keep track of stuff through the computer.

Things like Stamps.com has totally revolutionized it where, like, an issue of Phase 7 would come out and I’d have to spend 5 hours at the post office and I would be that guy that everyone hates who puts a stack of a hundred things on the counter. [Laugh] Everyone’s just groaning and want to kill this guy. Now I’m like, “hey, it’s just me!” and drop stuff off, or schedule a pick-up. It’s a great time to be a self-publisher. It really is.

I’m sure, looking at Dave Sim and the Cerebus Guide to Self-Publishing probably helped a lot in terms of giving you a base of where to start from. I have that book as well and it’s incredibly informative.

AL: Oh, yeah, that was another big turning point for that, reading that. It’s like, wow, you really can just do this yourself. He’s got that great graphic where it shows the artist with his head up the ass of the publisher who has the head up the ass of the distributor who has the head up of someone reading comics. You have to take Dave Sim with a grain of salt, but that one quote that’s some like, “why pay a publisher 90% of your profit to do something an intern could do for you?” Basic bookkeeping or whatever. So that kind of stuff made a lot of sense to me, and it evolved into me self-publishing “Basewood.” Just having that complete control and having the book exactly how you want, that’s always been important to me. I’m not adverse to being published, and I’ve had a couple things published by major publishers, but I always want to have something that’s self-published because you’ll have total creative control. It’s very satisfying to just do what you want not have someone telling you what to do, or worrying about the marketing department or whatever.

So, taking “Basewood” to Kickstarter. I know part of the reason was you wanted this nice big, deluxe hardcover book. But as someone who has done self-publishing for years, how has Kickstarter changed the game, in a manner of speaking?

AL: I think it’s interesting because I feel like Kickstarter right now is sort of controversial. I keep seeing it pop up in Blogposts that read, like, “Kickstarter Fatigue” or whatever, you know? If you’re my friend and you’re in the comic community, well, everyone is doing a Kickstarter now. So one pops up every week and you’re like, ugh, I’m a broke cartoonist, I can’t afford to chip in $100 to all my friends things. So I guess I can see that as a problem of it.

But, for this project it made a lot of sense. For me, personally, I think Kickstarter is an amazing tool — but it needs to be used correctly. I never contribute to projects where it’s like, “pay me to draw a graphic novel! I’ve got a great idea and I need $20,000 to give me time off my day job to draw this book!” I’d never contribute to that, because you’ll never see that book. Most people, we see people show up at the Center for Cartoon Studies all starry-eyed and in their first year they want to draw a graphic novel, and it’ll be two-hundred pages you know, and then at the end of the year they’ll have fifty pages. Which is great, it’s a lot of work, but their spirit is still broken a little bit. So if someone is telling you they’ll get their graphic novel drawn in a year and get it to you, it’s like, no, they’re out of touch with reality.

Continued belowI think the main way to use Kickstarter should be, “I have a project. It’s done. Just need some help putting it together.” Like with “Basewood”: I was totally done with the project, you weren’t funding me drawing it, I just didn’t have $15,000 in my bank account to pay the printing bills. There used to be something called the Xeric grant which ended a couple years ago, Peter Laird from “TMNT” had set-up, and I think that was a good business model; their rules were very strict, you know? They did not help you draw your book, your book had to be done and then they’ll help self-publish and get it out to the community. I think that’s the most successful use of Kickstarter for cartoonists.

What did you find different about working on the Kickstarter model over how you’d been doing things previously on your own? Given that with Phase 7, obviously there were subscribers so there was income and people funding it, but this Kickstarter was people like me saying, “Here’s my money for my copy of the book.” That kind of publishing model.

AL: Well, it was interesting for me. In some ways it’s very similar, right? It’s just like, OK, I have 500 orders instead of 200. In my day-to-day life, I’m sending out issues of Phase 7, I also do a Pinball fanzine with my buddy John, so I’ll go to the post office everyday regardless of whether I’m doing a Kickstarter or not. I’m always mailing out Phase 7s and Dvoraks and all sorts of little things, so it’s not that different.

But, I guess it was kind of weird getting into the Kickstarter world because I was funded in two days. I put it up and it was funded. All these other people running Kickstarters messaged me and asked, “How did your thing fund so fast? What’s your tip? What’s the secret to get a Kickstarter?” And I said, “eleven years of self-publishing.” [Laughs] I’d built a community, I’d made connections with people, I had all these subscribers and all these things… I had a community in place. Most people who did the Kickstarter for “Basewood” had already read it. They’d subscribed to Phase 7, they’d read the mini-comics, and they just wanted to show their support. They wanted to see this beautiful hardback single volume edition as much as I do. So, you know, I feel like to me, it was more of a pre-order thing where other people could then find out.

What was really exciting was, because it was funded so quickly, it was on the front page of Kickstarter. Like, “What’s Hot!” or something, for stats that had shot up or whatever. And that brought people like you in, or other people who have no idea who I am, that just thought it was an interesting project. So that part was really exciting to me. I would say about half the people were people I know or people who have supported me in the past, but the other half were just total strangers who were excited about the project. So for me it’s a win/win; it’s a great system to pre-order and get it in front of more people, but from there it’s all pretty familiar territory. I had a database full of names, addresses to mail stuff out to. I think five a day is my goal; if I can sign and mail out five a day, I’ll get it out in a month or two and everyone will have their book.

And I guess you kind of answered this, and I sort of know it too, but in terms of the people that this Kickstarter reached that had no idea about your work, did you find that Kickstarter was as good of a promotional tool as, say, Twitter or Facebook or any kind of social media? I came across by just browsing the comic section of Kickstarter randomly, but there are other things in place now to help promote books.

AL: In a strange way, as a self-publisher, I feel like it is, yeah. It’s a huge marketing tool. Lets say I just had $15,000 sitting in my bank account and could’ve just paid for it myself without having to do a Kickstarter and just got the books printed, right? Then I just have 2,000 copies of this book and I’m sitting on them like, “Yay, I finished a book!” And I might be able to reach my normal 200 people, but I wouldn’t get the extra other half of the Kickstarter.

Continued belowThe other thing that has been happening, which is a really nice side effect that I didn’t think about, is because I’m signing all these books — I have, like, 200 copies that I have to sign and can only do a couple a day — but on Twitter, they keep popping up. When someone gets their book, they’re really excited, they take a picture and they post it on Twitter. “Hey, my copy of “Basewood” arrived today!” Chris Pitzer at AdHouse Books is helping me distribute the book through Diamond distributors, so I just mailed copies to Diamond like a week ago, but the book doesn’t hit stores until March or April. So from now until March, there’s sort of this constant thing in the Twitterverse of little pictures popping up. Little reactions from people who were already on my side, you know? So there’s this nice bit of publicity just from the nature of it slowly trickling out as I sign copies and mail them out into the world.

I didn’t notice any particularly, and obviously Kickstarter has growing pains and some people run into more difficulties than others (there are a few particularly famous comic Kickstarter nightmare scenarios), but “Basewood” didn’t seem to come into too many issues. Did you find that there were any major difficulties in using the Kickstarter method?

AL: It’s actually been pretty smooth. It’s like you’re saying, well, I’m coming to it from a background of self-publishing and I’m already doing a lot of order fulfillment. So I can see where, if someone is just a cartoonist who finishes a book and gets it printed but they’ve never done order fulfillment, well, that can be a nightmare. Or if someone’s like, “Wow, I didn’t realize how much work it is mailing 500 books out,” right?

The other part of this is, another class I taught at the Center for Cartoon Studies for a number of years was a publication workshop, which has Photoshop and all that stuff. You saw my Backer reports, but it’s definitely the biggest project and one of the most complicated with all the different things — I’d never done a hardback before. I’ve done print-on-demand books before and have a lot of experience preparing files for print because I’ve worked as a colorist for First:Second and stuff like that. So at least the proofing process part of it went surprisingly smooth. There was, like, one little hiccup at the end where the deboxing alignment was slightly off, but then we fixed it.

But I promised people the book will be out in April, and you should have it in your hands in April. You can see how, if the files were messed up and the proof copy showed up and I had to re-do it all and go back into my files and fix stuff, that could definitely tack on more and more time, with getting new proofs and having to check those. I’ve also heard a lot of people have trouble with color; my friend Ben Costa does a great series called “Pang,” and it’s beautiful full-color stuff, but the proofing process is much more intense since he has to tweak certain packages just because of the off-set printing. The color can get messed up easily, and he’s talked to me about that.

I don’t know if I’m just lucky or if I knew what I was doing, but when the book came I basically had three periods of proofs with almost no corrects. It went very smoothly and everything stayed on schedule, so no, I didn’t have any real hiccups. I don’t know what the other issues are that people have run into, but for me it was luckily pretty smooth sailing and I’m thankful for that.

So looking back on “Basewood,” now that we have these nice hardcovers of the story, how are you feeling about the book? You started it in 2004 and did it for 7 years?

AL: Yeah, man. It feels good! [Laughs] It feels good holding it in my hands. 10 years of my life! I started it in 2000 and finished it in 2011. It’s sort of a strange thing. I sat down a couple days ago to start signing them, and it’s funny — when you finish a graphic novel, it’s like, OK, that’s it. Not going to go deal with these characters anymore, it’s over. But now it’s like, oh my god, I have to draw them 200 times again in people’s books! So it’s been sort of funny revisiting… how do I draw this character? Oh, yeah.

Continued belowBut, no, I’m very proud of it. And part of the whole reason I went through Kickstarter is because I had, like, a very specific vision. There was this French edition of the book that came out last year and I really liked the size of it. I just got back from Angoulême, the comic festival in France, and comics over there are just on a whole different level. They just make American comics look like a joke. [Laughs] They’re done on beautiful paper, they’re huge, they print everything so beautifully and just run circle around all American publishers. So, I had this beautiful book and it broke my heart to think that I’d have to print it at 75% the size and I’d have to do a softcover or whatever. I understand why publishers have to do that because they have marketing departments and bottom lines and investors they have to keep happy, they have to turn a profit, but I’m glad that I didn’t have to make any compromises. When I hold “Basewood” in my hands, it’s exactly what I wanted. It’s exactly what I envisioned and I’m super happy with it.

And, I mean, it’s 10 years of my life, so I would hate to hold this book and think of all the things that could’ve been; if only it could’ve been better, if only it had that extra … thing that I wanted, you know. Instead I feel really, deeply satisfied. It’s been amazing to finally hand it to people and have them read it and get excited about it.

And how do you feel about your evolution as an artist and a storyteller? Obviously, we mentioned Dave Sim earlier, and you look at early issues of “Cerebus,” issue #1 looks nothing like #200, it’s on a whole other level.

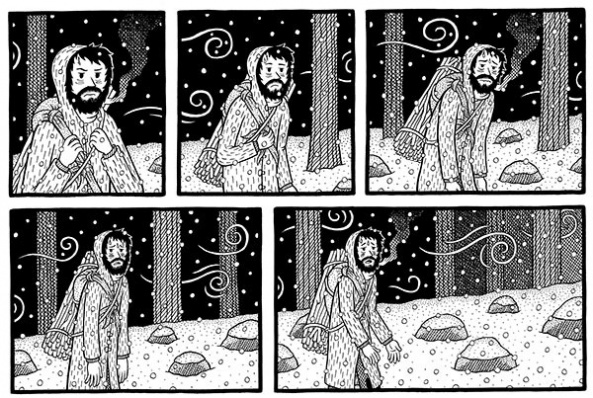

AL: It’s funny, because… You know, I finished it in 2011, and so even now, it’s been three years. It’s a little weird; I think as a cartoonist I look at “Basewood” and think, yeah, that’s pretty good for a first try. I have so many things I want to do that are different and hopefully better. I think the biggest thing I learned drawing “Basewood” — and “Basewood” is 200 or so pages and people are like, only 200 pages? Why’d that take 11 years? Well, I made a very simple mistake at the beginning. I was only on issue #5 of Phase 7 and now I’m on issue #19 and #20, and back then I wasn’t comfortable drawing small. So any cartoonist reading this, that’s my advice to you: learn how to draw small! [Laughs] I thought I wasn’t comfortable drawing characters small or anything, and I’d draw a character standing up and that’d be, like, 4 inches. And I wanted a four-tier page, which is about 16-inches and I need gutters and I need space at the top and the bottom, right? And I went down to the arts and crafts store and grabbed some 18×24 bristol board and thought, ok, I’ll draw at this size. So, just this one moment, I wish I could send a Terminator back in time and say “Don’t buy zat papah!”

It was a huge page, 18×24, and as you’ve seen, the book is now extremely detailed. Lots of cross-hatching and snowflakes and all these sorts of textures and details and stuff now. So much of this book was just spent filling in texture over large swatches of bristol board. That’s something I’ve definitely learned as a cartoonist and I will never do that again. [Laughs] I really hope that people enjoy how “Basewood” looks, because I’ll never draw anything like it again. That’s my motto from “Basewood”: Never again.

If you look at the issue of Phase 7 that came out right after “Basewood,” it’s all clean line and I’m using a mechanical texture to get a cross-hatching effect to get my grey tones. I’m trying to simplify things. I’m learning how to draw small, stuff like that. The physical size of my pages is about half as big now so I can move twice as fast. As a result, I’m a much happier, more productive cartoonist.

Continued belowSince doing something of “Basewood’s” scale and size, is this something that you want to do again? Something as complex as “Basewood?” I’ve since checked out Phase 7 on the website, and the most recent stuff isn’t this big epic fantasy story, it’s a comic about Weezer!

AL: [Laughs] Yeah. I think I probably will. I have other ideas for graphic novels, but I think right now I’m having… I don’t know if you want to print this, but I gave a talk at the Center called “FUCK GRAPHIC NOVELS!” [Laughs] I was just, like, I’m so sick of it. I think it’s unhealthy, I don’t think it’s a productive thing for cartoonists to do. There are other ways to craft stories that are much more satisfying and won’t wear down your spirit and crush you.

A cartoonist that has really meant the most to me in my life is Carl Barks. I grew up reading his work, but I was just a kid and thought, oh, these stories are great, you know? I wasn’t aware of the genius of them. Since becoming a cartoonist I’ve revisited his work. I tracked down the complete Carl Barks library that was published in the 80’s and 90’s, this 6,000 page collection of everything he’s ever done. And he is the best cartoonist that ever lived in my opinion. He created this deeply satisfying world out of Duckberg with Donald and Uncle Scrooge and Gyro and Huey, Dewey and Louie, all these characters, but his longest story would be 48 pages at the max. And he’d do maybe four of those a year! Most of his bread and butter as a storyteller was, like, ten pages. From 1942 to 1967 he drew a ten-page story for every issue of Walt Disney Comics, and you can open up any issue and find these Carl Barks ten pagers.

So in these small increments, as a cartoonist, you have ten pages and can craft a beautiful little story. You put another brick in the wall, though, so here’s a storytelling element or an aspect to the overall community, or here’s a new character — and over twenty-five years and six thousand pages, you’ve crafted a whole world. Every time you check back in with the world it feels a little more real, a little more satisfying.

That’s the thing that I’m really excited about right now. I’ve got a webcomic that I’m going to be launching in 2016, I guess, that I’m working on now that fills that kind of hole for me. It’s smaller storytelling chunks, but it fills a larger hole. So I’ll never have to sit down and draw a two-hundred page thing like “Basewood,” but in a couple years it will surpass “Basewood” and two-hundred pages with some deeper territory which I’m really excited about.

Is more Kickstarter something that you would like to do? Are you focusing on mostly building up Phase 7 even more? How are you looking at self-publishing in the future?

AL: I’m definitely going to keep doing Phase 7. I still want to get to issue #100 before I die. But, I don’t know. If you were to ask me while I was rolling four boxes of books from my storage unit home on my dolly, I might say, “yeah, having a publisher wouldn’t be so bad.” [Laughs] If you ask me a year from now when everyone has their copy of “Basewood” and they all love it, I’ll tell you Kickstarter was fun. I wouldn’t rule it out. On the whole it has been a very positive experience, so if I finish my first collection of my webcomic and I didn’t have a publisher ready to go, I would definitely consider doing Kickstarter again.

Right now, though, I’m just in fullfillment hell. [Laughs] My whole apartment is boxes and packing tape and books everywhere. It’s a lot of work. But, yeah, I’d do it again. It’s just such an amazing time to be a self-publisher. It’s so easy to get your work on Comixology or graphic.ly for eBook versions of your comics. You can do anything. People can draw comics and take a picture of it on their iPhone and just put it on Tumblr or whatever, and the whole world can look at it. It’s just a really easy time to tell stories and share them with people.

Continued belowI meant to ask, this is not the first time you’ve collected your work. Some of the early Phase 7 stuff is collected into graphic novels. So is re-doing those something you’d thought about? Maybe doing something similar to a “Basewood” style book? I’ve not seen those in print, so I don’t know what they’re like.

AL: The other collections, the business model that I have is I make about 500 copies of an issue of Phase 7 as a mini-comic and sell those. Once it goes out of print, I put the whole issue up online. If you want to read it for free, you can just go to the website and it’s all up there. Once I have a logical collection, like the first four issues were a collection and stuff, I just put them together and make a print-on-demand collection. It’s not as high quality. Print-on-demand is pretty amazing, but you can’t get a book like “Basewood” that is textured and has color stock and is two-color with high quality paper, hardback, all these extras that you can’t do with print-on-demand. I like a book artifact as you can see through the production at “Basewood,” so print-on-demand have this cover stock that I don’t really like but it does allow you to get a bunch of comics under one spine and, when someone orders it, a little machine goes whirr, spits out a book and sends it to someone — so I don’t have to do anything.

I don’t think I’d ever collect those into a similar “Basewood” book, because the economics of a book like that is you have to order in bulk in order to afford it and I’m not interested in having even more storage units full of books. With print-on-demand, it exists, its on the internet, people can access my work and if someone wants my collection they can have it. It’s no sweat off my back. The margins are much smaller, though, so printing in bulk, the unit price goes down so when you sell a copy you have a higher profit. It’s the exact opposite for print-on-demand; the unit price is extremely expensive, so for my cut, if the book is $20 when the person buys it, I get maybe $1 per book. But, it works for me! I don’t have to do anything.

So obviously, it sounds like you’re mostly just interested in self-publishing and doing your own thing and maybe growing Phase 7 and just going from there as a career cartoonist.

AL: It always feels a little weird when people ask my goals or whatever. I have achieved all my goals! I am living the dream. I get to draw comics and I get to mail it out to people who are excited to read them. I’m not beholden to anyone, I’m not in debt. I don’t have to check with anyone if I want the next issue of Phase 7 to be about a space adventure, I’ll just do it. I don’t have to check with a marketing department or a publicity team or whatever. I just do my own thing and I get it out there.

If someone wants to publish my work, they’re welcome to contact me; I’m not adverse to that. But for now, I’m very happy self-publishing and getting my stuff out into the world.

I’d rather connect with an audience that’s super stoked to read my work than a giant audience where half of them hate me.

For more information on “Basewood,” including how to get your own copy of the book, head on over to Alec’s website. For more information on Phase 7 and how you can subscribe, look no further.