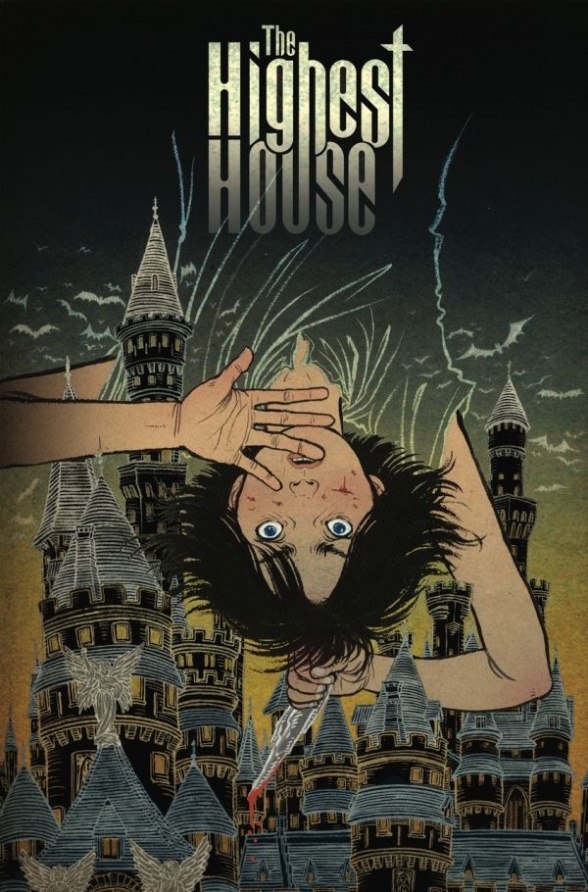

Michael Carey and Peter Gross, the duo that brought you “Lucifer” and “The Unwritten,” are back with “The Highest House,” a new fantasy series following a young slave named Moth as he struggles with the political machinations of an oppressive society and newfound magical power. French readers were able to read the first album of “Le Haut Palais” from Glénat, and this February the first album is being printed in English by IDW as two separate issues.

We recently had a chat with Gross and Carey about the world of “The Highest House,” the magic that influences it, the effect on the European model on their creative process, and more.

The first issue hits stores on February 28th, 2018.

“The Highest House” begins in the country of Ossaniul. What kind of country is Ossaniul? What is its place in the wider world of “The Highest House?”

Mike Carey: Ossaniul is a country with a violent, war-torn past. In terms of technology it’s roughly on a par with the late medieval or early renaissance period in Europe – and like the Europe of that time it’s a patchwork quilt of warring dynasties and proto-states.

In the not-so-recent past, Ossaniul was ruled by noble families whose power was based on alliances with magical entities. Then there was a war with the neighbouring country, Kovik, and these sorcerer-princes lost. The Koviki are monotheists. They worship a single goddess, and they forbid all other worship. They have systematically eradicated the bloodlines of the Ossani sorcerers, as well as seizing all their property as spoils of war.

The one Ossani custom they did adopt was slavery. In Ossaniul you can be made a slave in a dozen different ways. Your parents might choose to sell you, or you could be sentenced to slavery for committing a crime, or you could take church alms to keep from starving and become the property of the church. It’s a pretty brutal place. But as in ancient Rome, slaves can buy their freedom. There’s a certain amount of social mobility, which is used as an argument in favour of the system. Even the lowest of the low can rise through their own efforts, the rulers say, so the only thing that’s keeping you down is yourself. Which of course is the argument the haves have used against the have-nots since time immemorial.

Peter Gross: I think the slavery in Ossaniul is a peculiar kind of slavery in that it is completely ingrained into society and very few seem to even question it. It isn’t so much brutal as it is insidious. It even has a certain status to it as we see it in the culture of Highest House. I think it’s more parallel to the subtle ways that the lower and middle classes are used by the wealthy in the real world, and how rarely that system changes. It’s economic slavery, not race or ethnicity based, and you aren’t born into it.

The protagonist of “The Highest House,” Moth, is a slave with a specific role: he’s a roofer. What drew you to having a main character who is a victim of a world where slavery exists? And why a roofer, in particular?

MC: Moth’s status as a slave – and his desire to stop being one – is very much the core of the story. We meet him first as someone who has no power and no autonomy. His fate has been decided before he was old enough even to understand what was happening to him. But then through a series of what seem like coincidences he meets an ancient magical entity who offers him unlimited power in exchange for a single trivial favour.

Which might seem like the starting point for a story with the moral “be careful what you wish for.” But Moth is smarter than anyone gives him credit for – and more ambitious. He doesn’t just want his own freedom, he wants to end slavery as an institution so that nobody ever has to go through what he’s been through. And that wish is the engine that sets the story into motion.

As we’ll see, Ossaniul is on the cusp of change. And Moth becomes one of the agents of that change – an insignificant person who somehow alters the course of history, but not necessarily in the way he originally intended.

Continued belowAs to why he’s a roofer, we just wanted to give him a trade. And since he’s way up high a lot of the time he gets a bird’s eye view of the world of the rich and powerful. Which means the reader does too. We get a sense of Highest House through the eyes of a marginalised outsider, but an outsider who paradoxically has a ringside seat.

PG: I think making Moth a roofer was a genius take by Mike! It leads to the whole visual take on the world because it makes the architecture of Highest House into an essential character in the book—and I love that. And as we find out in the course of the story, Highest House is an actual character!

The buzzword used a lot by fans when talking about fantasy stories these days is “magic system.” Does the magic used by the inhabitants of Ossaniul have clearly delineated rules, or is this more in the vein of old sword and sorcery where all we really know about the magic is that it’s strange and terrible? Is its effect on the world subtle and hard to see, or is it flashy and dramatic?

MC: We’re not going to get hugely specific about the rules, but we’re all about the mechanisms. The study of magic is forbidden in Ossaniul, so nobody knows very much about how it used to work. We see a few self-trained adepts using sorceries that depend on replicating partly-understood words and gestures. But then we also have non-human beings with almost limitless power – and we learn that most Ossani magic was based on alliances with these entities rather than learning a system. If you’ve got a contract with one of these creatures, who according to the official state religion are evil demons, then you can do pretty much anything. But the small print will get you if you don’t watch out.

PG: This story is less about magic, and more about Moth’s relationship to one of the magical beings Mike mentioned. It’s like Moth is a tiny little bird flying around this massive supernatural thing that reaches out and touches him from time to time.

You have both said before that “The Highest House” has a large cast. Was this always the intent, or did the cast grow as you both fleshed out the world? What creative challenges does having a large cast present?

MC: We always wanted this to be a story with a broad scope – the story of a whole society at a crossroads, although our entry point is just this one child’s coming-of-age drama. You can’t really make sense of what Moth does unless you’ve got an idea of politics and religion in Ossaniul, and those things are only interesting in a narratve if you can express them through the interactions of actual characters. There *is* a history essay that was included in the first French edition, but it was really just for fun. What matters is what’s happening now, as Moth starts to clash with some of Ossaniul’s vested interests, not as part of a conscious plan but because their agendas are what he has to fight.

PG: The larger the cast, the longer it takes to draw. Designing a world and each passing character who passes through it is a daunting task. The whole project has taken me longer than I anticipated partly because I love creating all those new things and I want them to feel real.

When people think fantasy series with large casts and political themes, it’s hard not to think of A Song of Ice and Fire. Are there any external influences for “The Highest House” that may be surprising to readers, be they fiction or non-fiction?

MC: Game of Thrones was definitely at the back of my mind, not when I first pitched the series but as I was writing it. It’s hard to escape from something that influential and ubiquitous. But Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy was a big influence on me, too. Probably bigger than [George RR Martin]. “Highest House” is essentially Gormenghast, and Moth is sort of a cross between Titus and Steerpike. Although I like to think that he’s less of a douche than either of those guys.

Continued belowPG: Mike didn’t mention to me the Gormenghast was an influence for him on “Highest House,” but it was the first thing I thought of when reading the script. I hadn’t read that series since I was a teenager, but I got the audiobook of it and listened a lot as I was drawing the house/castle just to get that feel of an unending, impossible to comprehend the entirety of it, sort of place.

Some of the ideas about the relation between fiction and reality that eventually became the core premise of “The Unwritten” were lightly touched on in “Lucifer.” Were there any themes or ideas that came up in “The Unwritten” (or any of your other works) that are being explored more thoroughly in “The Highest House,” or do both of you feel that this is something completely new for you?

MC: “Lucifer” was overwhelmingly about freedom and self-determination – and about the things that make those propositions difficult, or sometimes impossible. In that sense “Highest House” is picking up another thread of the same argument.

It’s less existential here, though, and more political. There was very little politics in “Lucifer,” except occasionally in the ‘Heaven and Hell’ sequences. When we were on Earth we were dealing with individual dilemmas and destinies, not broad social movements. In “Highest House.” we’re trying to convey the idea of tectonic plates shifting in the background. A society in flux. Moth’s story is a microcosm. Lucifer’s was more like a parable.

PG: I think “Highest House” is very different than either “Lucifer” or “Unwritten,” which is one of the reasons I’m enjoying working on it. It’s very character driven—which is a nice break from the more plot driven and meta take on storytelling of “The Unwritten.” This feels very much like a novel to me, and I’m trying to visually supply that feeling of a very real but different world. Both “The Unwritten” and “Lucifer” had a very large playing field and felt structured to go on a long time. “Highest House” is much more intimate in scope and very centered on Moth’s coming of age story. And now that I think about it — there’s no Father issues in this story!

The first volume of “The Highest House” was originally published in France by Glénat as a 64-page album. Has this publishing model affected your creative process to any significant degree?

MC: Yeah, I’d say it has. The French album page is very different from the US comic book page. We were working to a very different rhythm, with fewer big splashes and more of a “proscenium arch” uniformity to the scale of the images. Having said that, this is Peter Gross we’re talking about. He found ways to manipulate the page and movement within the page that were breathtaking.

It felt like a big canvas. 46 to 48 story pages per book, with up to ten panels per page. Each album contained about as much material as a four-part miniseries in the US. We were able to fit a lot of storytelling into each book. But we had to learn the rhythms, which are very different from those in a mainstream US book. Weirdly, I’d say that my storytelling became tighter and more compressed in some ways. I’m not sure why.

PG: The BD format is a blessing and a curse. Those bigger pages take way longer to do because we’ve taken advantage of every extra bit of room to cram lots of story in. I told Mike not to worry about how many panels he put on a page and he didn’t! It was challenging, to say the least.

Mike did a great job of creating break points in the story that would work to make the shorter US issues — though it did cause a little confusion for Yuko when she came on to do the US covers! But for me, the biggest change was not being on a monthly schedule. After many years on “The Unwritten” coming out every month I was a bit burned out and I needed to recharge my artistic batteries. I drew this with a level of detail I could never get close to on a monthly book, and I rediscovered the artistic roots that brought me to comics in the first place. I hope it shows in the final product.

“The Highest House” is being colored by Fabien Alquier. After approximately 70 issues of collaboration with “The Unwritten” colorist Chris Chuckry, is it at all odd to see someone else color your work? How does Fabien bring the world of “The Highest House” to life in a way that’s unique to him?

PG: I loved working with Chris on “The Unwritten,” but I knew going into “The Highest House” that we would probably be using a European colorist. I was happy with that because I wanted to benefit from the great printing and the larger page size of the BD format. That said, picking the colorist was the most difficult part of the art process. I relied on our editors, Olivier Jalabert and JD Morvan to lead the process so that the result would fit the demands of the French market. We tried a few colorists, and even did some pages ourselves (with my partner, Jeanne McGee) but nothing clicked until we tried Fabien. I’m really relying on him now to flesh out the world and carry the mood. I’m very happy with the result!