Launched after “Journey into Mystery,” Marvel saw fit to team up Jamie McKelvie and Kieron Gillen for a new volume of “Young Avengers.” The first follow-up to use the characters in their own book after Heinberg and Cheung’s epic story with them finally concluded, the book displayed a different side of the characters as they were all forced to grow up as the Mother parasite attack, relationships blossomed and crumbled and the world was saved in a way that the adult heroes never could. And now, after a year, the book has come to an end; with the season wrapped and both Jamie and Kieron agreeing that it is time to move on, Kieron was kind enough to sit down with us for an exit interview on the series.

Read on as Kieron talks frankly about the book, its success, its failures, its relationship with the fans, “Journey into Mystery” and more (and be sure to come back soon for the second part of our chat with Kieron about his and Jamie’s new book, “The Wicked and the Divine.”)

So my first question is, how are you doing? How are comics treating you today?

Kieron Gillen: OK. What’s happened this morning? Well, I finished a script, so, productive, which is always a good thing for a Friday. The year so far has been pretty damn good. I was quite down last year but this year I’m quite up again, at least so far. The Image Expo of actually put a smile on a face. It’s essentially going to a place with so many exciting new projects and so many you people dig, and you’re just generally hanging out. So we stayed a couple of extra days and basically just spent some time with the Image folk who we’ve been friends with for years. So, yeah, I’m probably as energized as I ever am, which is not very much because I’m basically an Englishman who runs on business and despair as is our natural wont. How are you?

Oh, I’m pretty good. I don’t think I can complain. Yet. I mean, the day’s early for me, it just started. But you actually led into what I was going to ask for my next question, which is, after Image Expo and looking ahead towards prospects for 2014, when you look back at 2013 — which we’re going to a reasonable bit in this interview — how do you feel about the past weighed against the future?

KG: It’s interesting, yeah. It’s personally quite hard work, and workwise… I’d be a fool to complain about how anything went, everything was hard work. I was trying to work out what was actually the easiest book to do, and that might’ve been “Uber.” When you’re doing an incredibly dark book about World War II, there’s loads of research and very painful material – and that’s the breeziest. Though that’s kind of unfair to “Three,” “Three” was probably equally pleasurable in some ways. Pleasurable is the wrong word; it’s equally pleasurable and difficult, work being like that.

I look back at 2013… I think, “No plans survive” — was that Clausewitz? “No plans survive first contact with the enemy.” No, Von Moltke! Man, those 19th Century Germans. “Young Avengers” wasn’t as good as I wanted it to be, but it was pretty damn good. It’s that sort of situation where I always want too much, and I want everything to be impossibly good. It’s not as good as “Watchmen,” and that of course is ridiculously high standards and you’ll always be disappointed by whatever you end up, but on the other hand if you aren’t thinking about it then I don’t think you’re trying hard enough. I’m aware this is odd to say in a book that’s ended near the top of a hell of a lot of end of year lists, and could be argued as one of (if not the ) best reviewed of the Marvel NOW books… but I wasn’t looking for Top 5. I was looking for #1. And even if I got that, I still wouldn’t be happy. So, next year: Watchmen! Or more self-applied whip. The latter, more likely.

Continued below

I think you’ve said this before, certainly, but looking back on the run of “Young Avengers,” how do you feel about the book that you and Jamie book together? And I know you’ve said it multiple times, that you had a set goal, that you had said what you wanted to say with these characters and this book.

KG: We basically did a lot of really cool things, and it’s kind of like, we had this statement… We tried to ask basically a series of questions in “Young Avengers,” and most of them were, “Is it possible to do X, Y and Z?” And some of the answers were yes, some of the answers were no, and some of the answers were, “mmm, maybe.” Can you do a big pop art statement book at one of the Big Two, and the answer is “yeah, mostly.”

In terms of the stuff we managed to get away with, it’s pretty astounding, both in terms of content and in terms of structure, in terms of some of the games we got to play. Having the book end with two jam issues and putting everyone in together, that’s pretty rare, so the fact that we got to end it on our own terms. Fundamentally, we got our own book cancelled! That doesn’t really happen very often in terms of, “yeah, we’re done” and everything wrapping up.

It’s not that I couldn’t work out something else to do, but it just didn’t seem the best use of our time as human beings. That sort of thinking fed into “The Wicked and the Divine.” The idea of, you’ve got two years left to live, what do you do with it? And that’s kind of… that’s the same for every human being in the entire world: you’ve got ten, twenty, thirty, forty years to live, or even a year. Both of us could die of a heart attack half-way through this conversation. How are you going to spend your time on the Earth?

Talking to you, apparently.

KG: Exactly! There’s a grim future for you. [Laughs]

At the same time, “Young Avengers” is about the new. It’s about saying, here’s another way of doing all the things in superhero books. There’s very, very few tropes of convention there; we probably did too much stuff. Some of the experiments worked better than others, and some of the magic stuff went right to the audience and some of it went right to different parts of the audience. It’s very telling that the people that really got it really fucking got it. So, with our priority of “Young Avengers” being a book about the new, it kind of felt, rather than doing more “Young Avengers,” the odd duty to having made that statement would be to do something else, you know? In the same way we spent fifteen issues teaching the “Young Avengers” not to follow their heroes, that theoretically you are the problem, you need to essentially make your own myths and following those heroes is fundamentally a trap. With all of that stuff bubbling in, the idea of us just doing that again is, like, no, I’d expect to have a Patriot figure appear before me and start tormenting me. And I would deserve it.

How does writing something like “Young Avengers,” where the idea of pop is built right into its very core, differ from writing something like “Three” or “Iron Man?”

KG: In “Young Avengers” I had a load of ideas. It was like “Phonogram” on some surface levels of the interest in pop. “Phonogram” was always kind of our experimental ground for trying really, really wild things, and some of that attitude went into “Young Avengers.”

“Young Avengers” is basically a holographic structure. It’s written to be re-read; major reveals about character kept until the end so that you can then look back on the structure and see what that changes. It’s kind of like, it has this mixture of being a very shiny surface, it’s ridiculously shiny, and then if you have to move your head slightly you’ll see something — it’s a hologram. And the fact that that becomes quite explicit with the stuff at the end, with the point of it being fractal, designs within designs within designs, most of the things have at least multiple meanings or uses. I mean, look at the title of the first arc.“Style over substance” is what we knew people with a certain aesthetic preference who didn’t click with the book would go for first as an insult… so we made it extremely easy for them. If you all someone sees is the surface then they’ve got a very shallow reading of “Young Avengers.” Sorry we didn’t take you with us, but when we were doing what we were doing, we were hardly surprised.

Continued belowSo, yes, that prickliness is part of our whole pop “thing.” Pop bands are all in some degree irritants; some people fall in love with them, and some people really fucking hate them, and that response is a necessary part of the endeavor, if you know what I mean. It’s sort of a book about myself and how I respond to humans in different areas and I deal with my own bullshit and realize, oh, yeah, my bullshit is just me and that’s part of what I do and I’ve got to sort of both control it and embrace it — and that to me is pop. The idea of doing a book with a surface sheen that contains multitudes, the disco ball model, with intricate lines and detail moving all around but it’s just a big ball of shiny. I’ve been doing this for a while. I know what works. I want to see what else can work, and this was one way I wanted to explore.

In “Young Avengers,” in terms of how I cut a story, in terms of the scenes I showed and the scenes I didn’t, that’s all part of the “Young Avengers” experimental agreement. The idea of working out a different way of telling superhero stories, starting at where most scenes would end. The example I always use is issue #11, where we join in at the end of the big battle, that would normally be the end of an arc; I’ve written that story in the paragraph descriptions of what came before. It was Lord Eldritch, but we end after he’s defeated because I’m much more interested in how it feels to slump out of a battle. That’s the sort of space you don’t normally see.

People aren’t always interested in downtime stories, but I’m interested in the downtime around the main event. A classic superhero story is a joyous and beautiful thing, but we’ve kind of seen that a lot before. Is there room for doing obliquely around it? YA’s successes suggests yes. I wouldn’t do that so much with “Iron Man.” “Iron Man” is a much more classical superhero story. I think most of my stuff warp a bit because my sensibilities are not 100% always the most mainstream anyway, in terms of being influenced by a lot of things outside the superhero mainstream. I say that not as a derogatory thing towards the superhero mainstream, I stress, but an admission I didn’t get into comics as an adult because of Spider-man. I got into it because of Transmetropolitan. All that stuff is in my head.

It’s the Gibson quote, “You never learn how to write books, you learn how to write this book,” and while for most that applies to novels, I think that applies to me in comics. I kind of work out what this individual book is and then see how to fucking do it. “Young Avengers” was a seasonal task; I had an idea that was quite simple, and the first five issues were relatively simple, to sort of ease people in. Then it kind of goes off the deep end and you’ve just got to hope that people will stay on and stay with the structure there. When I’m doing something like “Iron Man,” I’m quite arc based after the first year, with an added Claremont-ian “Here is the main story, here is the B plot and the C plot.” There’s not a lot of that going on right now in superhero comics, but I like it.

And with “Three,” it’s probably the most arch-plot I’ve ever written. This is a really major, key story I’m telling, it’s fundamentally a hero story of three people on the run from three hundred. I’m writing it like a multi-plot thing, there’s multiple protagonists, you get a lot of Nestos, you get a lot of the Spartan’s side and a lot of the antagonists. The book is structured around threes, with three people on the run and three narrative view points, and it all kind of cascades towards the mythic moments. If you’ve read issue 4, it’s pretty much where you see that, where you get that beautiful panel and they’ve reached the ravine and everything goes quiet… and yeah, we’re kind of changing tone from before – where it’s adventure stories tinged with social realism – into something that’s a bit more … mythic, if you know what I mean.

Continued belowI take apart stories and that’s just how it works for me. One of the things about “Origin,” which is a joy — I mean, “Origin” is probably the thing that was the most fun to do last year now that I think about it because Adam is such a wonderful storyteller. Issue #3 is pretty much all a nine-panel grid; issue #2 is slightly different and something else, but issue #3, because of the situation, the nine-panel grid became symbolic, so those kind of choices.

You work out how best to do a story, and that to me is comic writing and it’s the reason I don’t really write stories, as in I never got into comics to write stories, I got into comics to write comics. Even when I write full script, I’m interested in the comic page and the comic structure, because for me, if I was just in it to write a story I’d probably be writing in another medium. The point of writing for a medium is that you’re writing for that medium, and there’s so much of that in “Young Avengers,” there’s bits of it in “Iron Man,” “Three” is written in a very strict form and that’s obviously quite deliberate in trying to make it feel classic and epic as well.

I think one of the things that is kind of difficult at Marvel or DC, where these superhero stories just keep going and going and going, it’s hard to get the kind of books that are definitive takes on characters or definitive runs in specific books. I think with you, the first book of that style that comes to mind is “Journey into Mystery,” as that was a very completed story; yes, the book went on after you left with different characters and new directions–

KG: As I set fire to my character.

Exactly! So when you look at the completed arc of “Young Avengers,” do you look at it at all in similar ways to your completed run on “Journey into Mystery?”

KG: It’s a different sort of task. The pop statement thing was quite firm in “Young Avengers,” in that we did it explicitly for a year and we ended it the first week of 2014 but the last panel says 2013. It’s the idea of here is how a mainstream ongoing superhero comic could be in that year. It’s almost like an alternative dimension take on it, as in imagine a world where all the Marvel comics like this. That’s a terrible idea, as the idea of any book being the only book coming out is a horrible thing, but we could do stuff differently. Just because there’s one superhero story doesn’t mean it has to be like that.

We use a lot of multiple dimension stuff, and that’s kind of explicitly talking about the idea of … I use it as an ethical model really, to talk about ethical and existential conceit of letting the bad dimensions into this dimension. That’s on you. Lots of stuff in Young Avengers. It felt more like a prototype at times.

I wouldn’t say it’s like “Journey into Mystery” because it’s left open, it’s quite deliberately left open because I want to see these kids continue, but if they don’t it doesn’t really matter – it still is its singular statement. “Young Avengers” was kind of deserved to design two masters, both in terms of trying to genuinely improve the “Young Avengers'” characters and make them more self-sufficient. I wanted to give them their own mythology. I wanted, if they were to carry on doing “Young Avengers” stories in the future, for people to be able to go, oh, here is the Wiccan story, here is the Patriot story, these are bits of characters without dragging in the Scarlet Witch or anyone else. You can do it, but you don’t have to. I wanted to give Billy his own mythology; he’s never going to be the Sorcerer Supreme but he might be the Demiurge. Explicitly, the story was about giving them a future. So that was kind of our own want when fundamentally working in the mainstream Marvel Universe, and give these characters as much potential as I could. I wanted to give them a future, because in the long run, all tightly-woven Legacy Characters without their own story or point of their own other than “kids or stated successor of major hero” are pretty much doomed, or at least limited enormously.

Continued belowGenerally speaking, Young Avengers was a the prototype model for how superhero comics could be, a sort of state-of-the-art comic in 2014, and that was our second point. If you picked on those bits in issues there as a singular pop statement, you know, here’s a season of a television show where we try some things and people take what works and use it and take what doesn’t work and then use that… but yeah, I think if you go back and read it as a singular story, you’ll be fine.

I was trying to serve both masters, I wanted to genuinely help these characters within this universe, and I wanted to do something by itself because me and Jamie had never done a mainstream Marvel comic for a period of time together, and it probably felt overdue. I think maybe, if “Young Avengers” had a fault, it’s that if we did it a year before I think I would’ve been less frenzied. I think some of my frenzy makes at least some of the worst parts of “Young Avengers” in that I wanted it so badly… but that’s also its merits, as in the complete delirium and the teenage wanting it too much. I had to realize that problem of the book and realize to solve that problem to make it a point in the book.

I’m sounding quite down on it, but I’m incredibly happy in terms of how people respond to the book and the people who love it, I am not complaining in any way. I just have chronic over-ambition.

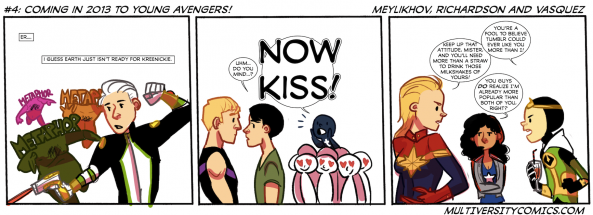

I think that’s actually a segue I was going to ask you later. One thing I noticed about “Young Avengers” is that the fan community was incredible strong for this book. They had a very, very vocal reaction to the series, Tumblr especially, and then you guys put Yamblr in the book as a nod to that. And obviously the book stars teens so they’ll be using things like Instagram, but did the fan community and reaction influence or play any part in the creative process for you and Jamie?

KG: The Yamblr one was an interesting look, because that was actually Clayton — or was that Jake’s idea? It was an editorial idea at any rate, so the first time I knew about the Yamblr idea was when it came back in the proof and I laughed my head off. In retrospect, it definitely wound up some people enormously. The people who didn’t like “Young Avengers” really didn’t like that, and it got a bit tedious, it kind of became emblematic of what some people’s problems were with the book. And on the other hand, well, maybe some people need to be annoyed. It’s like, dude, lighten up, it’s only a joke.

Did readers ever influence the book? Occasionally. It’s not nearly in the kind of “I was writing for them” way, but an awareness of where I wanted more or less clarity. You kind of have an awareness of is this book working, are people responding to the right bits, are people getting what you want from it? And it’s not like I sat and read everything everyone had and it’s not like I kind of changed direction of the book; the fact that it was designed as a singular thing means that I knew the end, I knew the end before I started. I knew the majority of the problems people would have with it, shall we say.

I come from a critical background so I’m always interested in what people make of it, and I try to keep a very open mind about it. But I like people’s expressions, is probably a better way of putting it. How does that actually influence the book? Very little, but in terms of making me do it again… When you get mail from some people who it means the world to and there’s some things that people have said to me about Young Avengers that’s just scary in that kind of… overwhelming? Magical?

I don’t know about you, Matt, and I’m assuming you wouldn’t be running a comic site if you weren’t somebody like this, but I’m somebody whose life was profoundly transformed by art, and that art meant the world to me. That’s what “Phonogram” is about, and the ideas in “Young Avengers” is very much that book to some people. “Phonogram” was as well, but the amount of people with “Young Avengers” and the range of people and what they got from it, that makes you realize it’s all worth doing. That’s what I mainly get. I’m somebody who likes writing for an audience, I’m not somebody who solely writes for myself all the time. I want to try and communicate and to be able to actually reach people on some degree, that is a big part of why I do what I do.

Continued belowAnd I think that’s fair, too, because like you said — I think literally the first time I ever wrote something to a writer or a creator of a book because the book meant something to me was actually “Phonogram,” so I totally get it.

KG: But you’ve got bad taste, though. [Laughs]

I do think it’s interesting, though, if you look at a book like “Young Avengers” and then you look at a book like “Avengers Arena,” which also has a very young cast. Obviously these are characters that people feel closer to, more attached to, even more ownership for, but the reaction to “Avengers Arena” was… like, remarkably different than “Young Avengers,” I almost want to say to a distressing state for Dennis. Talk to Dennis Hopeless about some of the things he heard from people is wildly different than talking to you about what you heard.

KG: It’s the yin and yang. I think “Young Avengers” was the yin to the yang of “Avengers Arena,” in terms of what the kids in the MU are for. It’s weird, because “Avengers Arena” is kind of a quite nostalgic and romantic book. I know people got very angry about it, very phenomenally angry about it and Dennis really got a baptism by fire on that book. The fact that it’s riffing on so many things, and there’s something profoundly… it’s almost like Grease, is how a friend described it to me. It’s a slightly different period that he’s pastiching but there’s so much heart there, and in the end I think Dennis got the readership. It wasn’t just people screaming at him. The thing about Battle Royale is you kind of do love those characters, you know what I mean?

And I got a load of shit as well. There’s people who entirely loved the book and some people who really do despise the book. Our thing was just kind of different, our problem is that me and Jamie are the first people to define the direction of the “Young Avengers” after the original creators. And as much as I have respect for what they did, we weren’t going to do that. We kind of disagree how the superhero we create should be, and there’s no way we’re ever going to do that. So the people who like “Young Avengers” the way it was, the whole legacy hero thing and who view that as implicitly a good thing, weren’t so interested in the concepts we were throwing around which is entirely their right. Yeah, they fucking hated us! There is some amazingly vitriolic stuff out there; Jamie did the quite sensible thing which was to just start blocking people from the off. Jamie is smart like fox. I plan to be more like Jamie in the future. This may involve wearing a wig.

But, yeah, a lot of people liked “Avengers Arena,” and I think it kind of probably averaged out in the end. Actually, I’m wrong there. Just deluded. Dennis had it much worse than I did. Hugs to Dennis.

So, I’d like to talk a bit about what I feel is one of the biggest parts of “Young Avengers,” and that’s Loki’s involvement. When you finished up your work on “Journey into Mystery” and there’s this incredibly powerful moment illustrated beautifully by Stephanie Hans of Loki killing himself, did you know that you were going to continue — or that you even wanted to continue his story into another series? Because I remember you mentioning that old Loki came back because if you hadn’t done it, somebody else would’ve, and you wanted to do that moment on your terms.

KG: I knew at the start of “Journey into Mystery” that I’d be doing that to Loki, so that was always my endgame. I knew it would be tricky for whoever followed me. About halfway through “Journey into Mystery,” “Young Avengers” started coming up, in terms of if I wanted to do “Young Avengers.” Which made me realise that the person who had to deal with the tricky task would be me. As a point in my story, I had to actually end it the way I always planned. “Journey into Mystery” needed that finality in the end, it needed the problems of supervillain and the problems of being a story and being anguished by the existentialist howl that was the end of the book. How to follow that?

Continued belowConversely, we were already talking about the next step for Loki. Me and Lauren, we were already sort of talking about the book that eventually became “Loki: Agent of Asgard” and what became Marvel NOW! and that there’d be a Loki book there. I wanted to basically… You know, I mentioned earlier how I wanted to improve all the characters, to make them more useful and robust, and that would be my Loki. I took the Loki who came out the end of “Journey into Mystery” and I wanted to teach the acquired lessons and get him away from… I wanted to side-step the concept of change a little, and Loki ends up quite fatalistic at the end of “Young Avengers.” I wanted him to be the best story he can be, which of course is a bit meta, perhaps unsurprisingly. That’s a weird sort of a sentence, in that life isn’t going to be straight and narrow and you need to be as good as you can for as long as you can until the option is taken away from you, and that may not be much but it’s all we can get.

So, I kind of knew about half-way through “Journey into Mystery” that I’d be following, and I really like the idea of Loki as his own conscience, and the fact that Loki was that mentally distressed that he was hallucinating a conscience was kind of the underlying thing that leads to the reveal at the end… I seeded Loki being a reality warper quite early and all of the things that led to the structural chaos at the end. So, it’s all in the book.

There’s probably three sentences in the last couple issues that you could probably underline. “If we don’t save each other we ain’t got jack,” from Miss America. “You’re never going to be Captain America,” and Prodigy’s “One thing I learned from you guys is saving the world from yourself is the first, most necessary step.” Pretty much all the characters learned those lessons in different ways, and Loki especially the third one. Loki was the ultimate part of the statement, in that Loki was the big baddie all the way through. Mother wasn’t it, really; Mother was a tidal wave, but it was always all about Loki as the biggest fucking problem because he is a big fucking problem and he learns to realize that and stop that. He manipulates himself into doing it, the point being Leah was actually Loki’s therapist.

So for me it’s not about any characters specifically, it’s kind of the story. I have the themes, I have the structure where the cast, in their own different ways, faced those problems, and they find their own answer to succeed and end in a slightly better place. You either improve your life, or you fail and end up in a slightly worse place and realize you’ve made a mistake. The point of Marvel Boy and Kate versus Billy and Teddy as a love affair is just to see a love affair that fails, and Marvel Boy fundamentally fails because of a lack of communication all the way to the end, a dream of something that wasn’t really there. That’s kind of inverted through Billy and Teddy.

Were you afraid, when you were putting this book together — and, obviously, a big part of Marvel NOW! is that everything new-reader friendly, #1’s all over the place — were you afraid that any of the references to “Journey into Mystery” might not carry over into “Young Avengers” for those new fans? You’re obviously no stranger to seeding references into work, or even callbacks, and “Young Avengers” also has Kid Nullifier from “Vengeance” and Oubliette from the “Marvel Boy” mini-series, but those aren’t books that I think are very widely read any more.

KG: It’s tricky, isn’t it? One of the bigger problems of the first issue is me basically having to basically explain the entirety of “Children’s Crusade.” I fought uphill on that and thought I’d be better off being a bit less respectful for the continuity and just saying “fuck it, I’m doing something else.” But I kind of wanted it in fairness, and part of me was sort of inventing ways to explain stuff. I mean, with Loki, to start with, we just need to see that he’s Loki as a kid and I delay the “Journey into Mystery” stuff to issue five, and by then it’s become a big part of the plot that the audience wants to know about. The basic is, ghost Loki has took over his kid body and you don’t really need to know anything else other than Loki has assassinated himself. He is now basically picked up the life of the Kid Loki character. That’s all you need to know at that point. Later on I added Leah, but Leah is of course introduced by herself, so here is somebody who is important to Loki and this is why she’s important to him.

Continued belowIn the same way with Oubliette, and I even said this in the bloody solicit for issue eight, we made a joke about extremely obvious exposition hidden in action or something like that. Them going across the dimensions was basically telling everything you needed to know about the characters, so you have Marvel Boy getting scared by Oubilette and the line is then “She’s the first reason I loved Earth.” So here is Marvel Boy’s ex, she was important to him, he’s the first reason he loved Earth, and that’s all you need to know really. And I hid that in an action sequence. With Leah I do it in a very different way.

Even with stuff like the Demiurge, literally the reveal for it leads the Young Avengers across all the dimensions to explain everything to the reader, which probably means something meta. So it’s that kind of, rather than just say this stuff, I turned it into the story and used the story structure for explaining everything you need to know about them and these relationships. It’s kind of like… do you watch Game of Thrones?

And I’ve read the books, yes.

KG: I’ve read the books as well, but one thing I like about watching the TV show is the adaptation in terms of their choices to try and ease this ridiculously over-elaborate world into the viewer. They’re still expositioning for the first half of the first series, you know? And they start with the zombies, which is to show the supernatural shit in this world — which is also what he did in the book, to sort of front-load it — and then here’s two families, here’s the king, and when you finally get to the third episode, they finally slip in… oh, by the way, dragons! You know what I mean? [Laughs]

So we’re going to ease you in one step at a time, and in terms of how much work or how much exposition the story can bear and how they introduce people, I think it’s a master class especially in that first series. I can just literally imagine the writer’s getting the book and thinking, “oh, bollocks.” So “Young Avengers” is a bit like that. I had all this continuity I wanted to get in and I wanted the core of their relationships, how to explain it and how to dramatize it … and that’s how I did it, to varying degrees of success.

So now that you’re done with the book and you’re done with Loki especially, Al Ewing has his ongoing coming out which is exciting —

KG: He’s amazing! I’m so happy his stuff is going well in America now. He’s a guy who has been so good in Britain for so long, and it’s like America has just woken up to him. He spent a lot of the noughties just doing work in Britain, but now he’s developed as this incredibly developed action and philosophy and pop writer, and it’s great to see basically a fully-fledged writer emerge on the scene. He’s an incredible guy.

So with all these characters, do you feel like there’s anything left unsaid or any sort of Spirit of the Stairs moments you have with these characters?

KG: In terms of “Young Avengers? Not significantly. The fact I left them in a better place… I say better, it sounds like I’ve improved them, I just wanted to make them more useful. That’s what I did with Loki, in terms of making an entirely more interesting and useful Loki, that’s explicitly what I tired to do. Stuff like Arno in Iron Man, here is an interesting angle to explore and see how much is there. I kind of like adding stuff rather than mining old continuity, is a better way of putting it. If I am going to mine it, I’m going to integrate it in some interesting way. But that’s kind of the point, you know? Look at what Hickman does, with Hickman bringing the New Universe stuff in and giving added value to the Marvel Universe? That sounds like a shareholder meeting, but it’s adding narrative value. I try not to just play with the toys. I try to add a little more paint, and a few gizmos.

Continued belowI joke that I’ve got in my head the front cover of a Miss America solo-series, and it’s just called “AMERICA!” [Laughs] But it’s a good title for a book.

It is, and I imagine it would be eaten up by the fanbase very quickly.

KG: Yeah. I’ve not got time to write, but that’s the sort of book I’d love to see someone else write.

So… bits and pieces. I did have ideas for the second year of “Young Avengers.” I was asked if I wanted to carry on, or do the Loki book, and both me and Lauren knew we had to move on. Lauren felt she had to ask and we both thought it was a better idea for me to say no. It’d just be returning to past glories if I did “Loki: Agent of Asgard.” I’m quite happy, I think. Maybe in two years time I’ll wake up and decide I really want to do another Kate story or whatever, but at the moment, no, I’m just happy to have known them. That last page in “Young Avengers,” that “liked.” All the characters are me, but Loki there, that’s me. I very much clicked the “like” button in that photo. It was great to know those guys, and I’ll miss them.

And you got in your Zombie Kate in at the end there.

KG: They were not ready for her! We didn’t plan that all the way, but at the end there it was like, “Hooray! We managed to get in a tiny nod at a running joke.” Zombie Kate solo!

So for my very last “Young Avengers” question, there’s one thing in the book that I might’ve missed. And I don’t know if you had paid it off, if I wasn’t paying close enough attention — there’s that story that was done in “A+X” of Kid Loki and Mr. Sinister, and I don’t remember that ever coming into play again. But it sort of seeded this relationship, this idea of what Loki might do when he’s watching Sinister. Was that something you put in the book and I missed, was it something you had plans for?

KG: It’s not a “Young Avengers” story. The kind of point of “A+X” is they’re stand-alone adventures. I was asked to do a Loki vs. Sinister story. It was literally that simple; I got a call from the X-Office suggesting it, and they’re two of my most known — in terms of characterization, it’s my Sinister and Loki that are the ones people talk about. I thought it wasn’t a bad idea because they’re both trolls, in terms of the point of the characters is they’re irritants. They’re modus operandi is to annoy one another other. It’s kind of science vs magic, faith vs religion, so having them together philosophically sort of made sense.

Talking about the whole of “Young Avengers,” there’s things that people can explore a narrative on, there’s lots of extras and new stories they can dig into there. So I did that on my “Thor” run, when I left the Loki clone of Doctor Doom, and here’s something that someone could use. For me, I could pick up that and run with that, and now we’ve got Mr. Sinister with the Loki DNA, and Loki doesn’t think he’ll be able to do anything but Loki has been known to be wrong. It wasn’t a Young Avengers story, but it’s something I left for the Marvel Universe. Al could easily pick up and run with that, or anybody could; it was never really meant to be part of “Young Avengers.”