Poetry can be a tough sell for some people, for reasons that aren’t really apparent. We all sing along to song lyrics, and what are song lyrics if not poetry? Maybe it is the experience of being taught poetry in a stuffy way in school that turned folks off?

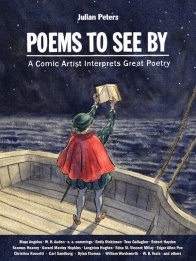

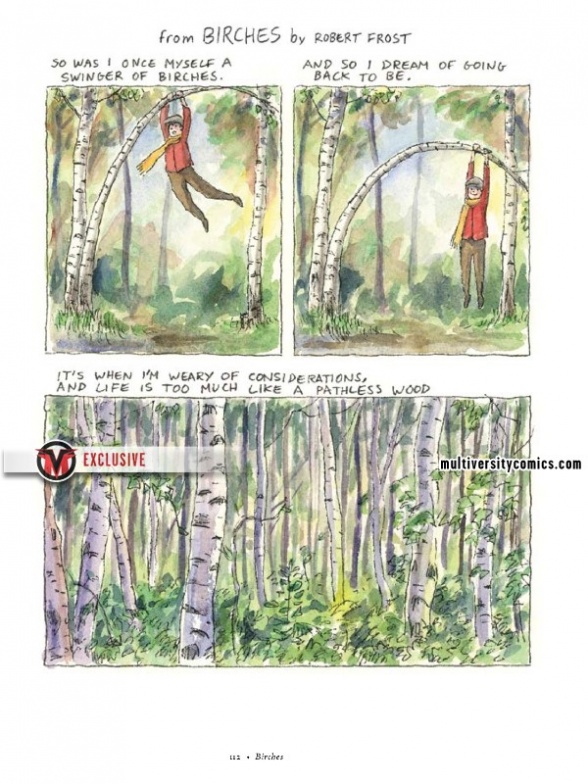

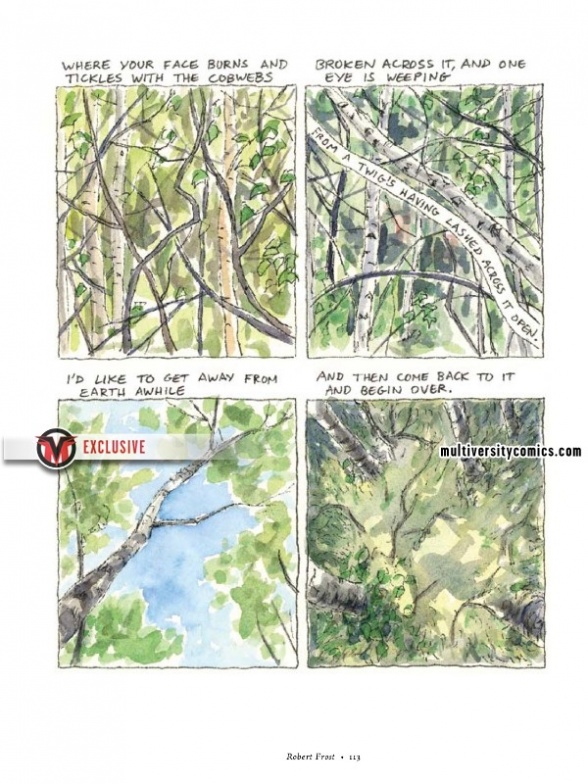

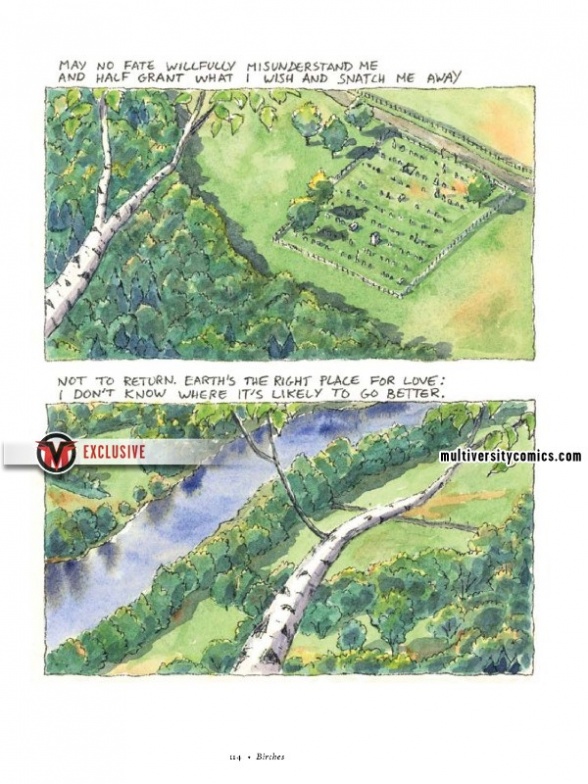

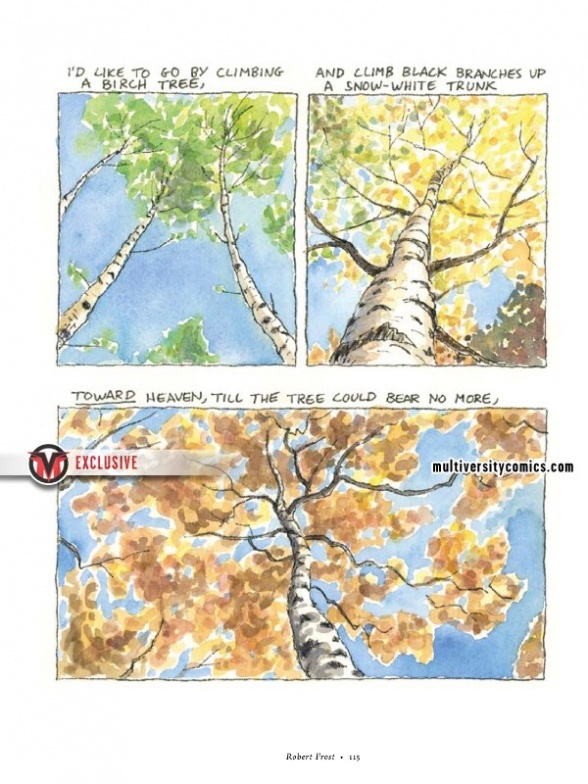

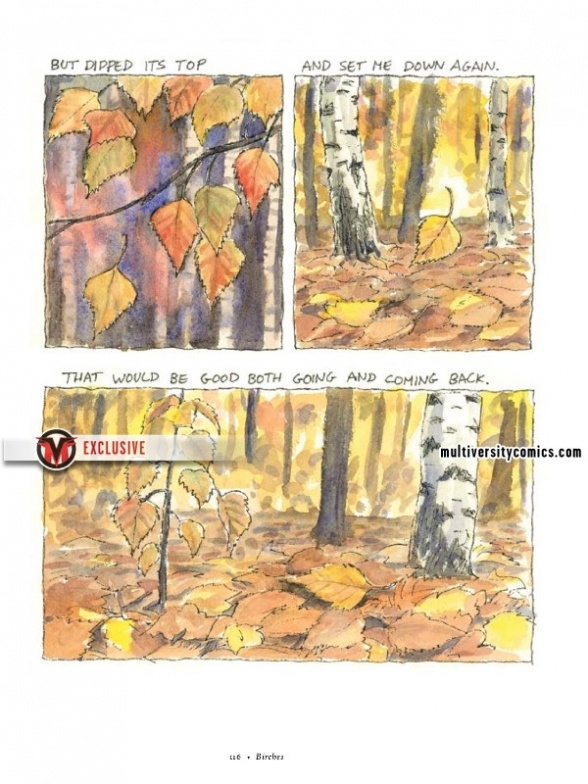

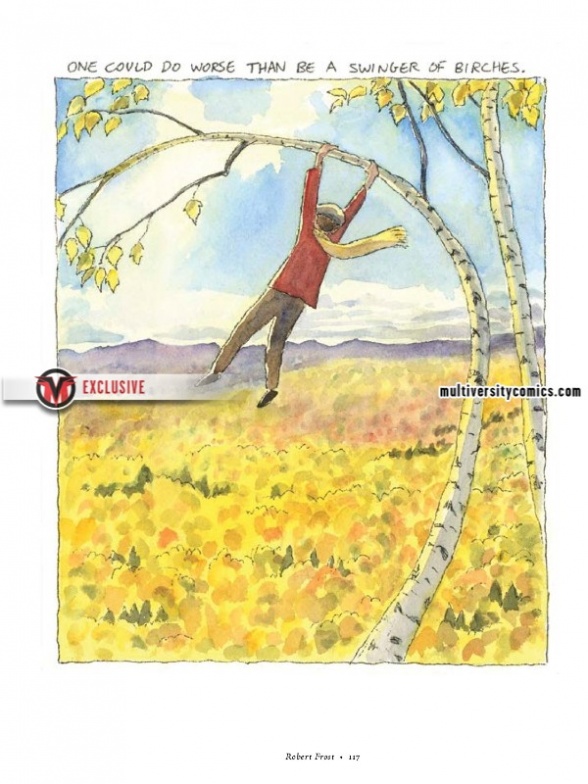

Regardless, Julian Peters wants to change your opinion about poetry. “Poems to See By: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry” is an anthology by Peters, who illustrates poems by folks like Maya Angelou, e.e. cummings, Ezra Pound, Emily Dickinson, and more. Today, we’ve got an exclusive first look at one of the sequences, “Birches” by Robert Frost. Today happens to be Frost’s birthday, so there is no better day to celebrate his work than today.

But we’ve also got an essay from Peters about being a former reluctant reader of poetry as well. Enjoy both, and make sure to pick up the title when it comes out Tuesday, March 31 from Plough Publishing, just in time for National Poetry Month!

Written by variousCover by Julian Peters

Illustrated by Julian PetersA fresh twist on 24 classic poems, these visual interpretations by comic artist Julian Peters will change the way you see the world.

This stunning anthology of favorite poems visually interpreted by comic artist Julian Peters breathes new life into some of the greatest English-language poets of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

These are poems that can change the way we see the world, and encountering them in graphic form promises to change the way we read the poems. In an age of increasingly visual communication, this format helps unlock the world of poetry and literature for a new generation of reluctant readers and visual learners.

Grouping unexpected pairings of poems around themes such as family, identity, creativity, time, mortality, and nature, Poems to See By will also help young readers see themselves differently. A valuable teaching aid appropriate for middle school, high school, and college use, the collection includes favorites from the Western canon already taught in countless English classes.

Includes poems by Emily Dickinson, Langston Hughes, Carl Sandburg, Maya Angelou, Seamus Heaney, e. e. cummings, Robert Frost, Dylan Thomas, Christina Rossetti, William Wordsworth, William Ernest Henley, Robert Hayden, Edgar Allan Poe, W. H. Auden, Thomas Hardy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Philip Johnson, W. B. Yeats, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Tess Gallagher, Ezra Pound, and Siegfried Sassoon.

Reaching Reluctant Poetry Readers

By Julian Peters

A very long time ago, I was a reluctant reader of poetry. Throughout my high school years, I remember even actively resenting it. Poetry appeared to me then as a kind of secret code, encrypted enemy communication that we as students had been called upon to decipher. Wading through the obscure language and convoluted phrasing on a mission to uncover the answer to the unvarying question, “What does the poet mean?”, I couldn’t help but wonder why, if it was really so important, these poets had not saved us all a lot of time and trouble by simply stating in plain English what it was they had intended to say.

It was only once I had graduated from high school and entered CEGEP (the pre-university college level unique to the province of Quebec), that I began to respond positively to poetry for the first time. Within the course of a couple of semesters, this tentative appreciation crossed over into outright poetry fandom.

It is very difficult, once one has developed a love for something, to recall how one could have ever felt otherwise, and I have generally chalked up this dramatic shift to some sort of hormonal change, in the same way that, a couple of years earlier, the riff of an electric guitar would go from sounding like little more than noise to lifting up my heart as if on the swell of a tidal wave.

Reflecting upon this time a little further, however, there is a significant difference that occurs to me between my high school and CEGEP literature classes: in the latter case, the teachers were in the habit of reciting poetry to us. Several of my CEGEP teachers were also published novelists and poets, and even in courses not devoted to poetry, their deep appreciation for the beauty of the written language would occasionally move them to a dramatic rendition, from memory, of their favourite poems. I remember that these recitals made a strong impression on me, not so much, I think, because the poems had more power when heard aloud than when read on paper, but rather in the evident passion behind these impromptu performances, the almost physical delight being taken in the delivery of these lines.

Continued belowAlthough for the most part our poetry classes still involved figuring out “why does the poet say…?”, “How are we to interpret…?” and so on, these teachers’ undisguised enthusiasm betrayed the fact that there was more to these poems than simply saying something in a complicated way. Poetry, it seemed, could actually make you feel something. Its effect, I would come to discover, could at times be not so dissimilar from that of music.

I am surprised by how many people –even those who are otherwise voracious readers, even those who have dedicated their lives to studying and/or teaching literature—will confess to me that, in general, poetry leaves them quite cold. I have come to feel that this state-of-affairs may largely be the result of how we first encounter poetry in school. Even when individual teachers have a genuine love for the subject, it seems as though they consider it quite beside the point to talk about how beautiful or powerful a poem is, and the students are never given a sense of why they should care about poetry in the first place.

A lot more would be accomplished if students were not directed to reflect exclusively on what a poem means, but also on the spontaneous emotional responses it provokes, and how it does so. Teachers, I feel, should not hesitate to model these responses by sharing their own reactions, and to occasionally supplement the “what does it means?” with the occasional “isn’t it so beautiful?” and “I love the way…” While it is certainly worthwhile, for example, to attempt to determine whether the speaker in Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” is a living being or a ghost, it is also worth noting what a wonderfully haunting effect is achieved by the way the last line of each stanza is shortened from six syllables to four, and how charmingly these final four syllables evoke the kisses in the line “with kisses four.” Enthusiasm is contagious, and though they may not show it or even realize it at the time, a certain portion of students will have caught the germ of what may one day develop into a full-blown devotion.

I am often told by teachers making use of my comics adaptations of poetry in their classrooms that my works are a great way of making the original texts more understandable to a new generation of students coming of age in an era in which communication is increasingly visual. My hope, however, is that, along with facilitating a reflection on the meaning of poems, these visual interpretations will also communicate something of the way the poems made me feel. I like to think of these comics as my own poetry recitals, my own way –the way of a comic book artist– of expressing my love for the intensely beautiful creations that I once slogged through so reluctantly.