Gene Luen Yang is a little nervous about his next book. Why would the 2015 Eisner winner for Best Writer have even the faintest apprehensions about his latest graphic novel, “Secret Coders,” drawn by Mike Holmes, and releasing today, September 28th, from First Second?

Holmes’ art is adept and charming. First Second’s publishing record is enviable and publicity operations are deft. And Yang has already notched unprecedented plaudits with a whole gamut of works, from his own National Book Award Finalist graphic novels “American Born Chinese” and “Boxers & Saints,” to acclaimed writing on properties like Dark Horse’s “Avatar: The Last Airbender” original series and DC’s current “Superman.”

Moreover, “Secret Coders” is as ideal a project as you can imagine for Gene Luen Yang, a graphic novel series endeavoring to teach the basics of computer programming to young audiences, something Yang did professionally as a Bay Area high school teacher for as long as he has been a published author.

But I can empathize with his nervousness. I sit across the table from him at a Vietnamese restaurant as he gesticulates enthusiastically, wearing his usual ready smile and a comfortable T-shirt. For the first time in a decade-and-a-half, Yang isn’t a comics creator moonlighting as a technology educator (or vice versa); he’s now fully preoccupied scripting Clark Kent’s Twitter-era tribulations instead of troubleshooting campus networks, plotting Aang’s exploits instead of planning lessons and exams.

What makes Gene Yang nervous is the experiment he is embarking on with “Secret Coders,” because Gene Yang the Storyteller and Gene Yang the Educator are striving for harmonic convergence here. “Secret Coders” tries to tell a fun and engaging story, and at the same time, to serve as an authentically educational comic book. The stakes are high for Yang, an outspoken voice for the educational potentials of comics. And he embarks on this experiment with no certainty that the educative purposes of “Secret Coders” won’t drain the super-power out of a compelling story, nor that its narrative charisma won’t singe the glasses off of the informational clarity of his teaching mission.

“I’ve done comics that were explicitly educational,” Yang tells me, “and I’ve done narrative, but ‘Secret Coders’ is me trying to combine the two. When I started the project, I was looking at a lot of educational shows on PBS, [like Cyberchase], and it seems like for a lot of them, the characters are pure avatars. They’re almost personality-less, really just there as stand-ins for the viewer, for the audience to learn… The only problems they have are the math-based problems. It’s like, the characters never have problems between each other, right?”

“And I just thought, what if we took narrative qualities and put them into a fundamentally educational comic, what would happen? And the big worry is that they’ll get in the way of each other.”

Like me, Gene Yang came from a family of Chinese immigrants, grew up on a steady diet of superhero comics, and channeled his accumulated nerdliness towards a Berkeley education and teaching career. Like me, he finds it contrary-to-logic, though historically explainable, that his childhood teachers never used the potent medium of comics to teach, save for a fifth grade teacher who assigned a comics adaptation of classic literature. Oh, but add to that his high school computer science teacher, Mr. Matsuoka. (“I taught computer science for about 15 years,” says Yang, “and I basically just stole everything from him,” —the refrain of all good teachers). Mr. Matsuoka routinely used visual diagrams of the insides of computers, arrays and variables, binary ones and zeroes, to make the subject make sense and come alive for young Gene. It was the natural inclination of a capable teacher of technical subjects to create graphic representations and turn them into sequence.

“I don’t see comics as a better teaching tool than other media, I just think they need to be part of the teaching arsenal, the toolbox. And I think they’ve been ignored for a really long time, for not very good reasons, mainly historical [since the Wertham trials]. But it seems plainly evident that certain kinds of information are better communicated through comics,” Yang contends, citing airplane safety cards and Lego instructions.

Continued below“So it just seems weird that I went through thirteen years of K-12 education, and really, comics were almost never in the classroom.”

Yang rectified that when he became a teacher. He often tells the story of having to leave his students with a substitute, and deciding to leave behind lesson plans in the form of a comic the students read which delivered the lesson and an assignment. He jokes that the students much preferred Mr. Yang as a comic strip over his actual presence as a teacher, but I suspect Yang’s trademark humility is masking the reality, that his comics succeeded in what every teacher wishes their substitute lesson plans would do: leave behind enough of the essence, vitality, and consistent voice of the original teacher to maintain the class’s attention on the next step of learning. As opposed to the usual procedures when there’s a sub, maybe involving spit balls or something on fire in the trash can.

As cartoonist/teachers like Scott McCloud and Lynda Barry have demonstrated, the comics medium has a way of compounding that certain mixture of elements— the aesthetic appeal, the specificity of voice, the combination of linguistic and visual clarity, the ease of quick allusions and contrasts—that a practiced classroom instructor relies on as stock-in-trade.

In an interview with Will Eisner by Stanley Wiater and Stephen Bisette, republished by M. Thomas Inge, the Master describes his road between “The Spirit” and “A Contract with God” through fifteen years of instructional and educational comics, beginning with military training comics in an Army manual. Eisner recalls, “it was an impertinence at the time… My comics implied that their regular training material was not readable. Which was indeed true!… But the essential reason that comics work so well is because… imagery is the fastest means of written communication in existence.”

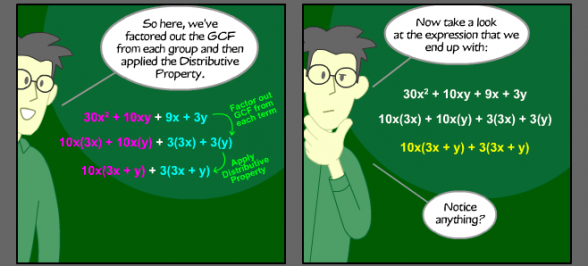

Indeed. But the narrative elements that comics can surround the instructional content with aren’t just frivolous window dressing, I would argue. Observe page 19 of “Secret Coders” below. Yang and Holmes’ protagonists, Hopper and Eni, supply three elements teachers dream of in classroom learning.

First, they use that quick imagery Eisner mentioned to illustrate concepts with examples and references. In the case of the example page above, our teachers Yang and Holmes have either already implanted a reference or can readily call forth some background in learners’ storehouses of knowledge: birds with open and closed eyes appear in the first 18 pages, and the coins, the chalk drawings, Hopper’s earrings, and sundry other tokens materialize throughout the story to illustrate concepts, sometimes almost randomly, as Yang/Hopper wink at in the last panel. These tangible reference points pop up all over the book’s setting, a mysterious school with Hogwarts-like secrets based in coding rather than in magic. If only Science teachers could orchestrate their lab materials with such efficiency…

But comics’ rich gift of visual shorthands, this quick availability of reminders, tokens, and references, which can materialize in comics as easily as a sketch, applies not just to handy demonstration materials like sidewalk chalk or coins. Those shorthands are everywhere in the narrative. In fact, all the characterization, plot development, and atmosphere-creating tropes in Yang and Holmes’ quick-moving and page-turning book, the private school uniforms and old brick architecture and eccentric school custodians, these activate familiar associations in the minds of readers and learners, also serving as mental resources the authors capitalize upon to unfold new information and concepts.

Second, Eni and Hopper engage in a back-and-forth dialogue, Socrates-style, which orders and structures the presentation and flow of ideas in a manner that resembles our critical and analytical thought processes: “What are you talking about?” “You make no sense,” declares Hopper. They voice the conversation in our brains, putting speed bumps on the hard conceptual turns, articulating the doubts and befuddlement we are hazily aware of in our heads. Teachers crave that kind of engagement, when the stuff becomes so interesting that learners are asking questions out of curiosity, or even frustration that comes from the appetite to figure things out. Learning is dialogical, and comics have ways with those kinds of words, from the rhythms of word balloons and silent panels, to the ability to personify all sorts of objects and abstractions while animating them with quirks, making them sweet or portentous or scheming or oddball. In translating the conceptual stuff of coding into a story, Yang gives flesh and bone (and feathers and engines) to all kinds of Technical Things I Didn’t Understand.

Continued belowWhich leads us to the third element comics can bring to teaching. This third thing is big. It’s what makes Yang nervous, but it makes all the difference. The third element is what everyone who teaches an online class struggles to approximate from the experience of attending a classroom one. It’s what every teacher knows can sour or sweeten any educational experience, sometimes definitively.

It’s the human element in learning. Much educational content gets washed in academic factuality, precision, neutrality, and objectivity. But our human instinct is to connect our learning to our social lives. Few of us learn anything in pure isolation from the inter-personal, emotional, and psychological trappings surrounding it. Even the most Spock-like quest for understanding is bound up in the language and communication we learn from interaction.

And few of us are Spock. Most of us…well…we read comic books. We study the details of geography, continuity, personality, and possibility when they have to do with our selves and our imaginations. We crave heroes, and we want villains. We want arcs of estrangement and reconciliation. We like information and we have curiosities, but we also need identification, tension and resolution, thematic resonance. We need stories, and stories for us are the shapes of what it means to be people.

Back at the Vietnamese restaurant, I ask Gene about the “Art Night” he has fondly memorialized in past interviews. I know he studied Computer Science at Berkeley, and quickly discovered, as so many cartoonists do, that college-level Art classes had little to offer his ambitions. Instead, he’s said before, his “art school” was his circle of creator buddies like Derek Kirk Kim, Jason Shiga, Lark Pien, Jesse Hamm, Thien Pham, and others, and their ritual weekly comics gathering, swapping shop talk and trade secrets, offering each other constructive feedback, goofing around and “talking crap.”

I’m insanely curious about this group, how they convened, what happened, how they figured into Yang’s comics origin story. Oddly but appropriately, Yang, a practicing Catholic, borrowed the notion of an “Art Night” from a weekly gathering of artists from a faith community he participated in, imported it with Hamm to a group of comics friends he met through the Bay Area’s Alternative Press Expo, and cultivated the weekly, sacred space of otherwise-employed, aspiring comics creatives like Gene Yang the computer teacher and Derek Kirk Kim the animator, nurturing their craft together.

When I press Yang for details about how the group influenced him, he says, “Just really simple ways. I’d never watched a Miyazaki film before I met Derek [Kirk Kim.] We sat down and just watched it together, and just listening to him talk about it made me realize why it was so important. My taste in story has been heavily influenced by his aesthetic. He just has a much more quiet, thoughtful way of telling stories, sort of allowing the stories to find themselves.”

Miyazaki’s films, where winds bend fields of grain for twice as long as American animation’s tastes would allow, filter through the languid scenes on wave-lapped beaches where Derek Kirk Kim’s “Same Difference” achieves its poignancy, into Yang’s wordless impact moments in “Secret Coders” or “American Born Chinese” when you read a hundred mixed intentions on the comically blank expressions of his protagonists.

And what did Yang learn from Art Night colleague Jason Shiga, the mad mathematical genius, recent Ignatz winner, Formalist creator of books like “Meanwhile” and the current, delightfully demented webcomic “Demon?” “What Jason demonstrated to me was, things you don’t normally think of as comics can be comics… He pushes the format.” Yang’s comics have been Master’s thesis, historical fiction, media advocacy, and teaching tool. My stack of Gene Yang books ranges widely in shape, size, and format— though none quite like Shiga’s unfolding maze of choose-your-own-adventure octo-flexagon comics.

What about gleanings from creator Lark Pien? “[From Lark], I just realized… I can’t color. I just look at her stuff and I’m like, Oh my God.’” In a smart move, Yang brought Pien aboard to color his art on “American Born Chinese” and “Boxers & Saints.”

Later, at a public appearance at Kepler’s Books with fellow First Second artist Ben Hatke, both artists are peppered with questions from young and old about how they learned and broke into comics. The wonderful and awful answer is the same confounding chestnut passed on and on at cons and forums: you make it into comics by making comics. Though degree programs exist, it sometimes seems you’re as likely to find the Eisner winner of tomorrow behind a hairdresser’s chair or in a computer programmer’s seat as you are at an art academy.

Continued belowPersonally, I interpret Gene Yang’s comics education offering a slightly different answer: You make it into comics by making comics with other comics makers. Yang hasn’t had one particular, distinct, publicized, collaborative relationship, like Stan and Jack or Van Lente and Pak. But even the most misanthropic and hermetic talents in comics ultimately rely on the friendship, patronage, and partnership of others; comics history is littered with exceptions that prove that rule.

So a guy as genial and gregarious as Gene attracts peers like moths to flame, and his story is peopled with friends who detected his geek genius and glow, and found gas to fuel it. His fifth grade chum Jimmy, who showed him how to convince their parents to drop them off at the library so they could take a detour to the comic shop AND check out a big enough book to hide the contraband. First Second director Mark Siegel, who sensed in Xeric winners Kim and Yang the pedigree of a whole new category of American comics creators. The changing roster of Art Night cronies, a ceremony for Yang that could only be usurped by the demands of fatherhood. Yang’s stories, both the ones he tells in conversation and the ones he writes into his comics, bear the distinctive marks of the communities he belongs to. In many ways, his comics are a gift back, odes to those networks, tributes to his peoples

This is not to discount the sheer, brutal volume of hard work and determination, nor the deep wells of talent and creativity, upon which Yang’s success rests. It’s merely to spotlight the ways Gene Yang learned comics in community, and in some ways, he writes comics as acts of community. Communalism. Communication. Communion.

Back to Yang’s conundrum. Can “Secret Coders” work? With critical feedback and sales figures still to come, it remains to be seen whether Yang and Holmes pull off the task of producing a solidly educational comic alongside a skillfully entertaining narrative. At least the experiment has time to play out, with the second book of “Secret Coders” slated for Spring, 2016, and Yang already at work on the third book.

Reading an advance copy, the experiment is barely detectable. The characters are lively, quippy, even affecting, in the manner of Gene Yang’s characters from Gordon Yamamoto on through his Jimmy Olsen. The story has a pace and pleasure that make it a quick, fun read, that make it feel nothing like homework, despite the “assignments” that wrap up each chapter, which seem deftly calibrated to “level up” and carry the reader to another stage of understanding. (Yang says they’re kid-tested. By his kids.) It will doubtless leave readers itching for more. My Computer teacher friend confirms the book is clever in the way it introduces coding concepts. Meanwhile, I’m amazed how much conceptual nutrition Yang and Holmes succeeded in seeping into my thick, math-resistant skull.

But I suspect Yang is not nervous about whether the book entertains or even if it sells. I suspect that the book is proof-of-concept for something that, to use Eisner’s word, might even seem “impertinent:” The crazy notion that comics have unique gifts for the educational enterprise. The idea that comics can thrive as media in the teaching arsenal. And perhaps the even crazier notion that they can thrive not only because they provide great diagrams, depict concepts with clarity, or look like the Sunday Funnies, a hilariously outdated proposal.

Maybe comics can become vibrant and effective educational tools because they tell stories, because they build communities, because they touch us on a human level. Because every programmer friend I know had programmer friends to commiserate with, and programmer heroes to admire. (One of Yang’s is his mother.) Because without Art Night comrades, there’s no artist. Without Mr. Matsuoko or Mrs. Yang, coding is a distant impossibility. And maybe without Eni and Hopper, it will remain so for so many kids.

Tomorrow and Wednesday, in parts 2 and 3, more conversation with Gene Luen Yang and reflections on his work, including the parallels of computer coding and storytelling, race/ethnicity and underrepresented youth, his creative process, and the cultural and spiritual themes of heroism and humor underpinning this humble creator’s work.