Once upon a time, Netflix Originals™ carried a similar cultural cache to calling something an HBO show. They were few, with short seasons, and seemed to live in a world all their own with creative freedoms and a guaranteed shelf life unseen in regular broadcast TV. This changed, be it overnight or slowly and then all at once, and now the name Netflix Originals™ is as useful a shorthand as saying something was published by Penguin-Random House.

Whether this story is actually true, or simply a nostalgia-fueled romanticisation, the feeling that there was once a time when one could count on Netflix Originals™ to be something special remained in my mind every time I saw a new project. I believe that The Way of the Househusband may have finally disabused me of that notion.

And, honestly, it’s not even the worst anime Netflix has made.

The first half of The Way of the Househusband dropped on Netflix on April 8th, 2021. It is an adaptation of, well, Kousuke Oono’s Eisner-award winning manga “The Way of the Househusband,” though adaptation is a word I use very, very, very, very, very, very loosely here. Why am I talking about it now, months after it dropped, which in internet and Netflix time is forever and a day? Well, partially because I take way too long to get off my ass to write things like this and partially so I could have the time to go back and rewatch two of my favorite gag manga adaptations to talk about just why Househusband failed so badly to connect with audiences.

I know I’m not necessary going to say anything new about this production that hasn’t been said in a better or funnier way than others have but if you’ll bear with me, I promise you’ll get a new appreciation for the creativity of a couple excellent gems, and maybe a glimpse into a universe where this show didn’t look like a comic transformed into a fan-dubbed motion comic. Wait. Sorry, I take that back. That’s an insult to fan-dub motion comic adaptations like Let’s Destroy Metal Gear.

Part 1: Animation is Hard. What If We…Don’t?

The creative choices behind The Way of the Househusband are, to put it mildly, baffling. For those who have managed to avoid this and have clicked on this article based on 1) the manga, b) my title, or III) a healthy, morbid curiosity, let me break it down.

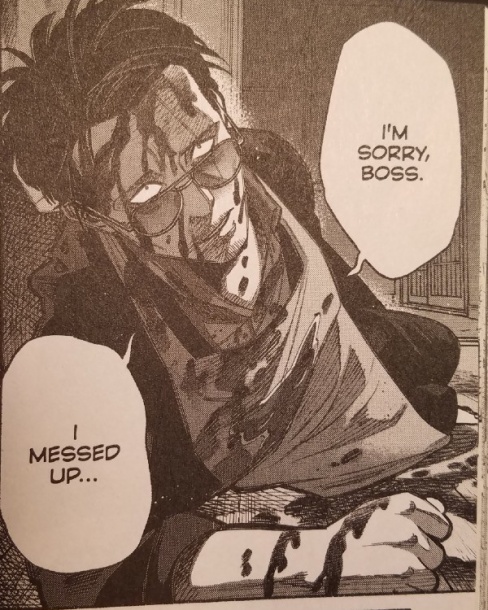

Way of the Househusband is a 1-to-1 copy of the manga in color with an audio component. I don’t mean 1-to-1 as in faithful, like one might call the Watchmen movie a 1-to-1 adaptation; I mean they literally took each panel and redrew it in the exact shape of the original without adding a single frame in-between. This was done not due to any time, staffing, or monetary limitations but on purpose. Vertical panels become pillboxed and are often in the exact same place on the screen as they are on the page. This leads to some exceedingly awkward shots that are just…well see for yourself.

As for the animation, it’s the barest of bare bones. The most we get in the way of motion besides the transitions are lip-flaps, an object/person that kinda gets dragged across the screen, and the occasional shaken frame. Yes, you read that right. To convey intensity and motion, they just shake the frame. Here. You can recreate it yourself. Here’s a frame from the show. Now shake your screen up and down but not too fast. Done it? There you go. You’ve replicated the show’s effects.

For reference, here’s the original panel from Volume two of the manga.

The sequence lands more effectively in the original not only because the art is in B&W, which is a better fit aesthetically than the bright colors and lack of deep shadows used in the show for creating a dissonance between Tatsu’s househusbandly actions and the Yakuza way he delivers it, but also because there’s an assumption of motion created between panels. With the anime, that assumption isn’t being made because when you’re the watcher, you don’t control the transitions between frames in the same way as you do when you’re the reader. Motion is expected in animation and when it isn’t delivered, that creates a cognitive dissonance.

Continued below

Despite all the problems I’ve had with the show, I did laugh at many of the jokes and every so often a trick caught my eye as clever. However, the jokes work in spite of Househusband rather than because of it. The stilted nature of the frames and the time spent lingering on each one ends up diluting the impact of the punchlines, forcing us to rely on the strength of the original material to shine through. That said, there is a way in which this show could have worked with limited animation and clever tricks.

Let’s say they wanted to lean into that aesthetic, relying on the jank to help amplify the jokes, like how in Demon Slayer From Animation Studio Trigger attempted to lampoon 70s cheap, ultra-violent ninja & samurai films/shows by having characters literally be paper cutouts they moved as if they were on sticks or strings against a static background punctuated with beautifully animated moments that break with the rest of the show. It was the right fit for the type of show they were making and served an artistic purpose that amplified rather than dulled the core concept. If this was the route they wanted to go down, what Househusband should have done is take a page out of Studio Deen’s playbook. Specifically from their production of Haven’t You Heard? I’m Sakamoto.

Sakamoto aired in April of 2016 and was an adaptation of the four volume manga of the same name. Created by Nami Sano, the original manga is fine enough but nothing special. However, when Studio Deen, an anime studio legendarily known for its stiff animation and cheap productions, adapted it, they transformed what was an OK to Alright manga into a brilliant anime that still gets laughs out of me to this day. They did this by leaning hard into the awkward comedy of the original and tailoring it better for animation.

Compare, for example, the climax to the first episode’s first half to the aforementioned “shake the screen to convey motion.” By this point in the episode, we’ve already spent 6 minutes watching Acchan, Kenken, and Mario try to bully Sakamoto and failing miserably, each attempt having been transformed into a stylish opportunity for Sakamoto to look cool. In a last ditch attempt, they ambush him in the Science lab and go for some good old fashioned “I’m gonna wail on you” bullying before a fire breaks out and a mop falls on the door, locking them all inside.

The bullies freak but Sakamoto has a brilliant plan. He begins to step back and forth in front of the fire in a special move called…Repetition Side Step. It’s utterly ridiculous from a story perspective and the animators sell that by having Sakamoto just kinda loop back and forth with a blur effect on him to pretend he’s going fast.

The animation is nothing special for that scene, and remains understated throughout the entirety of the show, but it’s just stylized enough to allow the rest of the material – the absurd situation, the earnestness with which the bullies start talking about how his slight breeze is going to put out the fire – to shine and, perhaps, even be enhanced because rather than being distracted by or focusing on the animation, we’re focused on the actions and words of the people. The show is methodical and slow in its movements in order to better highlight its strengths.

Moreover, Sakamoto uses the contrast between long static shots with looped animation (if any, even) and segments with more varied cuts and shot composition to heighten the inherent absurdity of what’s going on. Thus, when the punchline for the Science lab actually comes along in the form of a lingering shot on science teacher seeing these four goofs just kinda side-stepping next to a raging fire after having opening the door, the lack of flair and variety makes it even funnier than the scenes that preceded it.

You don’t even have to look that far in the episode to see this kind of thing either. The opening sequence of the first episode lasts about a minute and forty-five seconds and the entire thing is just a single shot of Acchan, Mario and Kenken passing a volleyball back and forth. We’re kept at a far distance so the details on their bodies are minimal and they don’t even have facial features. The entire scene is conveyed through their conversation. No body language, no facial changes, nothing else. The scene ends with them laughing before one of them bops the ball a little too far, they all go stop laughing and then none of them move. We just kinda linger on this scene for a good 15 seconds of silence as a title stinger appears and disappears in the corner.

Continued below

It’s super awkward! But that awkwardness is 1) hilarious and 2) useful in setting the tone for the show. It’s also a joke that would not work with a higher degree of animation slickness or a different shot composition. As the opening gag, and also an anime original, it’s the perfect addition to a show that, for the most part, is a very faithful adaptation of its source material akin to Househusband, specifically in how the episodes’ segments are neatly divided by their corresponding chapters. It just goes to show that a little leeway in adaptation can go a long way.

Part 2: Animation is Easy. What if We Quadrupled it All?

“The Way of the Househusband” relies on a combination of assumptions we make about the Yakuza and assumptions we make about housewives to create the basis of the humor, which is then sold through hard transitions between set-up and punchline and either through the absurdity of the situation itself or from other people’s reactions to Tatsu’s antics. Like, Tatsu decorating his house to look like a formal ceremony for his boss to celebrate his wife’s birthday is inherently hilarious while him dressing up in various outfits to look less threatening only becomes funny thanks to his wife Miku’s reaction of hopelessness. That joke is made even better because the punchline panel is on a page turn, heightening the anticipation just that little bit.

When this was translated to the screen, however, we lost all of the charm and while a joke like the above does work well for a limited style, others would have benefitted from a different approach.

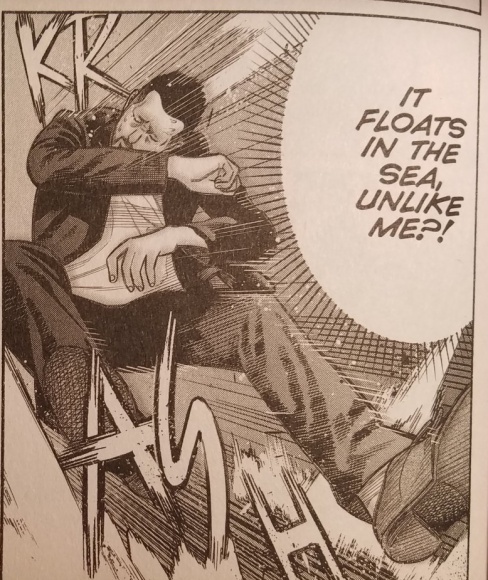

Take, for example, chapter 12, where Tatsu keeps giving some random Yakuza boss household objects like a rubber duck or a carrot peeler and the Yakuza interprets these as threats. That in and of itself is funny but Oono goes few steps further by not only having Tatsu look pants-darkeningly threatening when he says something like “Rub-a-dub-dub…it floats” but also by having the Yakuza boss’ legs give out in increasingly intense ways. To sell that kind of joke in animation, the production needs to understand how to properly go over-the-top with motion in contrast to something calm.

The production needs to be like Nichijou.

Nichijou is a 2011 anime adapted from the manga of the same name by Keichi Arawi. Anyone who has read my Soliciting Multiversity column knows I’m a huge fan of Arawi’s sequel series “City” so it’s no surprise that I’m here to rep his previous work. His manga is pure absurdist gold and conveys an intensity of motion & a clarity of action that visually rivals Akira Toriyama at his peak. As such, any adaptation would have to take a wildly different approach than what Studio Deen did for the off-beat and awkward “Haven’t You Heard? I’m Sakamoto.” Motion and a slick production is a necessity, so who better to get than Kyoto Animation, a studio known for just that.

KyoAni is a gem in the industry, a studio that pays salaried wages among other benefits, something Netflix & other studios could learn to do, and as such has a consistent, high quality to their productions. Nichijou takes full advantage of this, allowing the animators to go all out on transforming small moments, like trying to break open a pumpkin or interacting with a deer, into gut-busting, side-splitting, laugh-your-ass-off events.

And it’s not afraid to get weird either. Just take a look at this scene, which features Yuko watching the Principal wrestle a deer on and off for three minutes. The whole thing is patently absurd, laying a groundwork of giggles, but once the animators get to work, every twist and turn in the battle elicits sudden bursts of guffaws. Just look at how much effort went into those deer bucking scenes or the careful, subtle and vital fretting animations of Yuko.

Or take a look at this scene, which is centered around the Rube-Goldberg antics this piece of Yuko’s lunch goes through as she attempts to save it from falling on the floor. That level of effort and intensity of animation wasn’t necessary to convey the tragedy of the almost loss of her food. In fact, it wasn’t even necessary to make the scene funny but they did it anyway, and in doing so, transformed it from a gag into a masterpiece of absurdist comedy.

Continued belowNichijou relies on exaggeration to ludicrous degrees via detailed animation of mundane or simple events as the key to its humor. It builds jokes on jokes and uses repetition to make subsequent scenes even funnier. For example, take the below gif.

It’s easy to see where this is going from the start. The piece Yuko hits is gonna smack Mio in the head, and there will likely be a reversal, and it’s going to be a good old fashioned bit of slapstick humor. It’s not even a particularly highly-animated scene when compared to, say, the Deer Scene, utilizing a lot of the same tricks Sakamoto employ. However, the animation and keyframes that are there are drawn to maximize their motion and exaggerate the actions.

Yuko doesn’t just hit the piece; she smacks it. The piece doesn’t just smack into Mio’s head; it crashes, leaving a sizable divot. Mio doesn’t softly catch and return the piece to Yuko; she snatches it out of the air and lobs it right back at Yuko, sending her flying off her chair. The sharp cuts build the rhythm, along with where the animators choose to linger, while the character reactions and the intensity of the animation sells the rest of the intent of the scene. The cumulative effect is an energetic and hilarious scene, simple in premise but elevated by the execution.

Part 3: Adaptation is Versatile. Why Not Tailor to the Work?

It would be easy to pin all the failings The Way of the Househusband on “bad animation” and imagine a world where Netflix had or taken KyoAni’s ethos into their adaptation or even contracted KyoAni to animate “The Way of the Househusband,” obviously in a world where the horrific 2019 arson attack didn’t occur. It’s easy to imagine the level of nonsense we would’ve gotten from the “Rub-a-dub-dub” chapter or from a Haikyuu level of sports earnestness for the Volleyball chapter. And what a show that would’ve been. It’s not hard to see how “Househusband” would have benefitted from the Nichijou treatment, as the two share a style of exaggerated absurdity through motion rather than just visual gags.

However, treating the argument that “more animation = better” as a truism constrains all the myriad ways Househusband could have succeeded without the highest budget. Haven’t You Heard? I’m Sakamoto doesn’t have fancy direction, copious amounts of motion, or beautiful tableaus but it works all the same. In fact, it is stronger without them. That is because much of the comedy is that of the understatement, and Sakmoto’s calm demeanor works well to support a more subdued approach. This comedy of understatement is shared by the “Househusband” manga, coming out via its central tension between the shady violence of the Yakuza and the sunny mundanity of everyday activities like shopping, cleaning, and supporting your wife.

Househusband remains, however, a bad show and a poor adaptation. It’s just that the animation, or lack thereof, isn’t the issue. What ultimately brings Househusband down was the choice to not actually adapt and transform it from the static, reader-driven medium of comics to the fluid, director-driven medium of animation. No new angles, no believable motion to sell a joke, and a forced, lethargic pacing caused by time expressing itself differently in a comic panel.

When you abdicate that responsibility, as the Househusband production committee – not the animators and not the director – did, then you rob your adaptation of its room to become its own thing. It can only pale in comparison to the original and I cannot think of a worse fate for a project than that.