When Multiversity Comics first began, nobody cared about creator-owned comics and it was barely a blip on this blog’s initial radar.

Wait. Wait.

No. That’s… not quite right.

Let me try that again.

When Multiversity Comics began 4 years ago, the majority of attention given to the comics culture by us and most predominant comic culture blogs that we followed was directed towards company-owned comics from Marvel and DC, with smaller titles that weren’t already staple creator-owned series by the likes of folks like Jeff Smith getting little to no attention.

It’s a weird truth to admit, certainly not a universal one to every site, but it’s never the less true. Over time, the collective interest in creator-owned and independently published books on this site grew exponentially relative both to a) the amount of work we put into the site and the type of books we became more interested in covering and b) the visible shifts in priorities that have developed in the comic book culture, partially onset by the greater visibility and intense microscopic analysis that companies are currently scrutinized under.

Creator-owned comics see wider coverage today than perhaps ever before, with a renewed interest in the fight of the underdog. Covering company-owned properties is enough to keep the lights on, but the real passion and interest lies in covering just about everything/anything else.

So that was 2009. But where are we in 2013? We at Multiversity like to think we do fair and balanced coverage of both sides, even tipping the scale more towards the creator-owned world — but is there a specific reason why creator-owned comics are so damn important today when, outside of a chosen few, they weren’t a half-decade ago?

I’d wager there is.

And with the help of Eric Stephenson, Scott Allie and Chris Roberson, we may just be able to figure it out.

The Real Introduction

But before we begin, allow me to set the stage a bit so you can see where I’m coming from.

This past July in San Francisco, the second annual Image Expo was held to a packed house of fans. Held before San Diego Comic Con ostensibly to avoid having all the exciting comics announcements buried under headlines related to movies (and, in true Image fashion, to not be subject to the whims of anyone else’s rules and restrictions), Image brought the proverbial ruckus with various reveals that new books from all-star comic names like Rick Remender, Ed Brubaker, Matt Fraction and more were on their way. It was and is a pretty exciting time to be a fan of Image Comics, especially if you’re particularly drained by some of the events and trends present at the Big Two and the ouroborus nature of never-ending superdrama.

However, what makes this worth discussing beyond the general positive platitudes for creator-owned comics is this: all of these creators are creator-owned returnees.

That is to say, their names – as celebrated and big in our world as they are – were inherently “made” based on their work for hire at Marvel or DC respectively. Rick Remender’s “Fear Agent,” for example, was moved from where it first existed at Image over to Dark Horse, where it only wrapped up in 2011 after starting up in 2005; similarly, Matt Fraction took his creator-owned title “Casanova” out of Image and brought it to Marvel’s Icon, where the long-awaited third installment was finally released last year. These creators all started off with the same hustle you see in unknown creators today.

Now they and more are “back,” so to say, with more surprising creator-owned books announced every month — but it’s creators like them who are the headlines to which Image and other publishers can make waves. In terms of bringing the roof down and making a statement against the inherent monotony of IPs that will be re-used until this whole thing folds in on itself, mentioning that creators like Jason Aaron and Jason Latour are teaming up at your publisher or that Mark Millar is building a new shared universe at your company is the way to do it – and it’s inherently cause for celebration all around, because creator-owned comics are where we see some of the best work in comics today, no doubt.

Continued below(Using this situation isn’t meant to rag on Image, by the way. I think this site has proven to have an intense love for the books they put out. It’s just the most convenient/current example for this article’s purposes — and we’ll talk about this more later.)

This general transition of established creators moving away from strictly for-hire work seems indicative of a major change in how we view the creator-owned landscape. In fact, these announcements (regardless of how many will be found on your pull list or my own) seem to represent a strange change in the dichotomy of where our appreciation lies with this aspect of the medium — which begs to ask whether our attention is devoted towards the explicit exploration of something new in the most literal sense of the word or if, dare I say it, that creator-owned comics have simply become trendy.

Or to put it more simply: I’m beginning to wonder if we’re still looking for the Next Big Thing in comics or not. As a collective whole of people who read and make comics as more than a hobby, where do our priorities lie in 2013?

Certainly the interest creators show in spending most of their time working on new creator-owned books is a swing away from how it used to be. The general policy of “making it” in comics seemed to be that you’d start with creator-owned books and work until you didn’t have to toil away in that field anymore, getting picked up for stardom at Marvel or DC to write Batman and Spider-Man. That was the endgame for many; writing the characters whose adventures had been so important at a younger age was The Dream, and only a few seemed to shy away from that (or at least find enough success on their own to not even consider it).

That’s not necessarily the case anymore. Now some successful independent creators have sworn off ever working with either company, and that work at Marvel and DC need not even be a blip on their radars — both for monetary reasons and moral/ethical disputes based on company behavior. The times, they are a-changin’.

That creators like the aforementioned Remender and Fraction have found a comfortable place to work (at Marvel) and play (at Image) is a positive reflection of where the industry has gone.

But.

What I’d argue is that it’s not their work that has inherently made this a viable option, but rather what has happened to change the shape of the industry. Look at a book like “Chew,” which is often referred to as Patient Zero in this discussion: when it came out, it was met by headlines and instant sell-outs, as well as a bevy of subsequent additional printings — but it was essentially shocking because we had these random, no-name creators strike gold so impressively in the modern comic climate. And following that, the flood gates opened: since at least 2009 if not earlier, we’ve seen a big push in unknown creators getting major breaks at Image, and the Image “i” logo now delivers with it a certain level of respect, notoriety and reliability to a consumer as not just a publisher but a brand, a trust built with, “Chew,” “Morning Glories,” “Walking Dead” and many other titles.

So I’d argue that it’s with that respect that top-name creators not only want to come to Image but can do so via major announcements at an Image-produced convention of their very own.

But from a casual or more removed perspective, I think it’s probably fair to call the recent love of creator-owned comics a trend, if not just trendy (as I think “trendy” tends to come with some negative connotations, and that’s not my point). It wasn’t that long ago that everyone was throwing their weight into the superhero game for all the obvious reasons, but we’ve become more aware that within this kind of work lies a certain aspect that the creator doesn’t matter; just ask any fan who buys a comic just because a character they’ve loved for years has a cameo role. Now that Hollywood has basically begun mining comics in total for new movies and The Walking Dead has proven that there is major success to be made from adapting comics, it’s not at all a surprise that creators — whose main job, mind you, is literally to create — would want to explore options that give them more freedom and reward.

Continued belowWe’ve become increasingly more aware of strange operations coming out of bigger companies, and the importance of intellectual property has never been more important on a much larger scale. Fans and especially creators are starting to “get” how comics run, if not fully understand all the nooks and crannies, and it relates back to how they see their future.

For many fans, the unethical treatment of creatives that built worlds for monolithic companies is too much to abide. For many creatives, the idea of not having any kind of ownership of their work and creations is not an attractive or desirable one, no matter the paycheck.

In fact, to break the flow a bit, I’m reminded of a quote from Ales Kot in an interview I conducted with him for his new book “Zero” at Image:

“Suicide Squad” is a company-owned property, so the company has the last word on what I write. Therefore, unless I am given free reign, I will never be able to create something as creatively satisfying as the work I own myself, with my collaborators. That doesn’t mean I can’t make it a good story.

“Zero” is me having free reign. I am interested in having full creative control in everything I do.

Which illustrates the point of where we’re at today rather succinctly.

Not to diminish Ales or anyone else’s talent, though, but I speculate occasionally if the success and attention creators like him have found in the past year would still be given five years ago. Or even ten.

So Why Are We Here?

This shift, from publishing no-name creators with great ideas to big announcements about books from established creators (who also have great ideas, admittedly), is not something that has really been analyzed to any great degree. It’s something we’ve simply come to accept and acknowledge like an iOS update, having collectively experienced Image’s mighty rise to power.

After all: it’s rather impossible to argue that this is a bad thing, right? Because it’s not a bad thing, not in the slightest; having creators with recognizable names come to a creator-owned comic world is really only good for creator-owned comics, as it shows clearly that the viability of the medium isn’t strictly for a select few and that there is still room to create and shape the future by what we want to see today together.

If anything, it simply shows that comics and creators are more interested in getting back to their roots, not propagating a tired system. So over-analyzing it — to a degree — seems to imply that there’s something wrong with this. That’s not the point.

However, I think there’s some understandable paranoia created by this. There is a general fear present that the more published work being done by creators who are able to utilize a certain level of fame created elsewhere to sell their books could perhaps overshadow the work being done by the creators of tomorrow; that those who already are fighting to be heard with DIY comics, who thrive on the ability to hand-sell their work at conventions, are now losing their footing — or that small titles by no-name creators can’t make pull lists because of consumer budgets and priorities. I’ve seen the term “getting boxed out” on one occasion.

(This isn’t to say that Big Name Creators are guaranteed instant sell-outs, but the notoriety and acclaim of Fraction’s “Hawkeye,” “Fantastic Four,” “FF” and “Iron Man” don’t work against the current sales of “Satellite Sam” and “Sex Criminals.”)

It seems like a petty belief or argument to have, but it’s never the less one that exists. In fact, I’d imagine it’s very easy to see as a prevalent issue of sorts when your general “New Creator-Owned Comic” #1 by New Creators X and Y can get twenty reviews the first month of release talking about how exciting it is, but “NC-OC” #2 receives five reviews if that, perhaps one of which coming from a “top blog” if we’re lucky. We seem happy enough to celebrate that initial release — and that’s on us. But how we respond reflects how companies will react, both in buzz and in sales.

So to seek an answer to the question of whether or not creator-owned comics have become trendy or are instead seeing a Golden Age (or even some combination of the two), we will be looking at profiles of three different creator-owned comic publishers of today:

Continued below- The aforementioned Image Comics, our Publisher of the Year in both 2012 and 2011 (and, honestly, the biggest contender for 2013)

- Staple creator-owned and licensed comics publisher Dark Horse Comics, home of some of the most influential creator-owned books

- Newcomer Monkeybrain Comics, who have done pretty much everything differently from established business practices

In discussions with their top editors as well as through an exploration of the different methods of operation that these similar but different publishers have in their operations, we can perhaps gain a better understanding of the overall presence of creators and their books.

That’s the plan, anyway.

Shaping the Future at Image with What’s Next

First up is Image Comics, arguably the biggest publisher of creator-owned comics currently.

Founded in 1992 when the biggest artists in comics left the Big Two to do their own work, Image was a major player in shaping the landscape of comics in the early 90’s, particularly in terms of the output done in creating current staple characters and books — the biggest of which being Spawn, who went on to have his own film and still stars in one of Image’s longest running series (including spin-offs, alt-universe tales and no reboots/relaunches/renumberings). After seeing a meteoric rise in prominence over the last few years due to hit after hit in their new releases, Image has become the current Gold Standard for not only what kind of creator-owned books we consume but how we expect and want our creators to be treated.

Image is a company that has made a point of being entirely open in their policy and in how they view the business side of comic books. It is a combination of this, their output and the very candid and informative nature of publisher Eric Stephenson that has made Image a popular household name in the world of comics today.

So the question I immediately brought to Stephenson was: why is it that we’re seeing such a massive return to creator-owned from the older, established names? Sure, there’s a certain aspect of the old guard giving it up to the new, but why now, in the latter half of 2013 as we get ready for 2014, are we seeing some of the biggest creators head back to their former playing field?

For Stephenson, the answer is quite simple: creators have begun to realize that they don’t have to put up with these companies anymore.

“Well, I think a lot of it has to do with creators realizing they don’t have to toil away in a culture of intimidation and fear to be successful in this business,” Stephenson told us in an interview for this piece. “A lot of people aren’t familiar with how the comics industry actually works, but there’s a lot of bullying that goes on behind the scenes, on a lot of different levels, and I think many creators have grown tired of being wined and dined by their pal in talent management so that anecdotal information about their personal lives can then be turned over to some desperate little suit who calls up and makes all these veiled threats about their family’s well-being while hammering them with a contract.”

“It’s a story I’ve heard more and more often the last few years, and it’s almost comical, like a bad TV movie version of how the comics business works. It’s not everyone or everywhere, but there really is a consistent pattern of behavior that involves degrading talent in order to buy their loyalty, and I think people are getting wise to it.”

It’s an interesting response, and not the one you’d immediately think to receive (I’d wager half of you would’ve guessed “creative ennui”) — but it’s an honest one. Right now more than ever, people have begun to to be able to get a near first hand look if not a direct link into the way that a company like DC is treating their creatives, with a comprehensive timeline existing if you’ve forgotten some of the greatest hits of walk-outs and firings in the New 52. Horror stories about behind-the-scenes events are running rampant, either from a second hand source or on a creator’s blog directly, and it’s a bit disheartening to watch from the sidelines.

Continued belowAnd, honestly, I can’t have been the only one downright shocked when George Perez of all people quit working for DC or seeing Kevin Maguire end up at Marvel; if there’s anything that illustrates how poorly your company is doing, it’s two of your biggest and most influential creators ever leaving.

(There’s a flip side to this, mind you. Brian Bendis, for example, has often noted how well Marvel has treated him, including a point when the publisher took care of his family during a rather dark period. It’s not all gloom and doom, but there is still a noted and visible culture of otherwise exploited creators who are vocally unhappy with how they’ve been treated.)

And, of course, there is the issue of ownership of the work. Some if not most creators are aware of the situation and are fine with it, but to others it’s a raw deal, especially in terms of royalties. “I think everyone should give the men and women in the creative community a little more credit for being able to do basic math. 100% is more than 0%, no matter how you slice it, and if you want to own and control your work, the only way to do that is through creator-owned comics,” Stephenson notes. “And 100% control of your property’s media rights is more than 50%, just like splitting the majority stake in publishing royalties is more lucrative than dividing up the paltry royalties offered on work-for-hire books. And the big difference between royalties on creator-owned work and work-for-hire, the great thing about creator-owned work, actually, is that those royalties are yours.”

This isn’t to say that there are perhaps no random fringe benefits to working at a major publisher. To be fair, DC in fact had been known in the past to send checks to certain creators after the success of their Batman films. But as Stephenson continues, it’s nothing compared to what can be found when working on your own material. “Work-for-hire publishers go to great lengths to characterize their royalties, or incentives, as they’re sometimes called, as “voluntary,” and disbursed at the publisher’s discretion, making them a gift as opposed to an actual guaranteed form of payment. In fact, work-for-hire publishers reserve the right to change or cancel their royalty programs whenever they please.”

“Bottom line,” Stephenson says, “Success begets success, and when people look at things like “Saga” and “The Walking Dead,” or books like “Chew” and “The Manhattan Projects,” and “Fatale,” they realize it isn’t just one guy catching lightning in a bottle. They realize that if they’ve built up an audience for their work, they can stand on their own and be successful with material that they create, own, and control, and they can do it without being bullied or lied to by people whose sole motivation is making sure the numbers add up for everybody other than the creator.”

With all of that in mind, there’s still the aforementioned aspect of Image headlining with books from familiar names to discuss. I’d wager that I might sound like a broken record or even a massive idealist for assuming it even possible to announce who might be the next major name (there’s no Nostradamus in comics, as far as I can tell), but it perhaps stands as noteworthy that amongst Image’s announcements during the first Expo, Ken Garing and “Planetoid” was part of it. While Garing had gained a certain notoriety thanks to features on iFanboy (with Ron Richards getting credit from Stephenson in his keynote for bringing him the book), that was the “smallest” announcement of the night — yet in its own way, the most exciting.

We knew Morrison and Robertson’s new book “Happy” would be great, and we still assume that “Phonogram 3” will blow doors down when it arrives… but “Planetoid?” That faith was something else entirely.

So with Image being a hub of creativity , has Image lost any of its feelings towards the underdog? “Not at all,” Stephenson says, claiming that the notion entirely is complete fiction. “Which is why books like “Peter Panzerfaust,” “Five Ghosts,” “Todd the Ugliest Kid in the World” and “Sheltered” have all gotten a lot of play here over the last year.”

Continued belowAnd when asked about what he thinks is the next hit series poised to take off, Eric points out that Image has books like “Five Ghosts” by Frank Barbiere and Chris Mooneyham, picked up at NYCC from a self-published release and now an ongoing series at Image, as well as the brand new series “Sheltered” by Ed Brisson and Johnnie Christmas, which received a tremendous amount of buzz and success to the point that despite being discussed early on as a mini-series, it looks like the series will have a longer lifespan.

In fact, September alone will be a pretty big month for Image in terms of new content. Image/Shadowline will be seeing the release of “Rat Queens” by Kurtis Wiebe, author of the aforementioned “Peter Panzerfaust,” with newcomer Roc Upchurch (a book which, by the way, was not announced but heavily promoted during Image Expo 2013). This week sees the release “Zero” by Ales Kot and, as Eric explicitly notes, “you can rest assured he won’t get taken off it before his first issue hits the stands.” Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky’s “Sex Criminals” debuts at the end of the month, and we’ve also seen the release of “Reality Check” #1 by Glen Brunswick and Viktor Bogdanovic and a one-shot by Dirk Manning called “Love Stories (To Die For)” with Owen Gieni and Rich Bonk on art.

“I’ll happily put our track record with launching and developing new talent up against anyone else’s, especially when it comes to putting them on the same pedestal as more widely recognized writers and artists, because we are the only major publisher giving new talent access to the same platform as top tier creators. Other publishers wait for Image to road test new writers and artists before they even consider giving them work.”

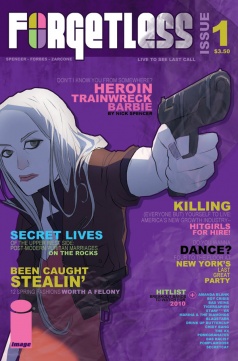

And he’s right. For better or worse, Image became a bit of a mining field for the Big Two as new creators were scooped up quickly in order to bank on their success. Nick Spencer is perhaps the first name that pops to mind, as Marvel and DC actually had a bit of a war over who could get to keep him around; DC gave him “THUNDER Agents,” Marvel gave him “Iron Man 2.0,” DC gave him “Supergirl” and Marvel gave him “Secret Avengers” — books were seemingly thrown at his feet because he was definitively the Next Big Thing. There’s even a comic about it.

(Nick is of course not the first creator who these companies have gone to Image to find and hire, nor will he be the last, but I like Nick a lot so he made for my example here.)

And what Stephenson points out about this so-called “change in operation” (or however we want to call it) is that by putting weight towards the bigger names, Image can then help develop an audience for the smaller ones. “We’ve got a new series launching in January from more or less unknown talent that I couldn’t be more thrilled about, so yeah, nothing has changed in that regard, unless you count the fact that the success of our other books is making it easier for the new guys to find an audience.” Fans of the award-winning “Saga” can find other science fiction frequently at Image, with “Rocket Girl” debuting soon for fans looking to start with something new, and all you’d need to do to see Stephenson’s point is visit Image at any convention and see the amount of books they have on display.

It’s essentially branding. Over the past few years, Image has developed a track record that speaks for itself. You may never have heard of these guys Justin Jordan and Tradd Moore when “Luther Strode” first debuted, but Image had proven by that time with their output that it was probably worth a blind buy — and it decidedly paid off, both for fans and the creators.

Now, with more established names coming back to Image, that aspect can only grow. Image today is what Vertigo used to be, and that’s not just a hyperbolic statement. There was a time when Vertigo was the name for exciting comics that pushed boundaries and truly presented what the medium was capable of, but the current administration of DC has let their imprint fall to the wayside. Vertigo is attempting to make a comeback, but that trust is gone. Image, on the other hand, is taking their place (in our world, the “i” stands for trust).

Continued belowSo with Image essentially utilizing its power for good and literally being the change we want to see, we can look at the resurgence and growth of interest in the creator-owned in a new light. To the average fan who doesn’t read blogs everyday, creator-owned books may essentially mean absolutely nothing, but creator-owned books collectively have begun to take a significant share of the market from the Big Two, with Image holding 5 books in the top 100 alone in August 2013 — though where we really notice significant action is in the trade sales. Image holds 4 out of the Top 5 trade sales in August, dominating still with “Walking Dead v1: Days Gone Bye”, a book that was originally released in 2006. That’s incredible, and it has put Image as one of the top two suppliers of trade paperbacks and graphic novels to the direct market, not to mention Image’s dominance in the New York Times graphic novel bestsellers list.

“If you add in the combined output of all the other publishers doing creator-owned material, that part of the market is absolutely growing,” Stephenson concludes. And given that Marvel and DC’s combined output is more than the entire industry combined, that’s no easy feat; Marvel and DC will always have an edge based on the amount of books they can put out thanks to double-shipping and shipping mandates, but the gap is beginning to close. Fans informed and non-informed are gravitating more towards what’s new — or What’s Next — whether it be through fan recommendations or their local hard-working retailer.

“I suspect that by the end of this decade, the marketplace will look much, much different than it does today.”

A Day at the Races with Dark Horse

So with Image essentially setting the bar in terms of how we see creator-owned comics and the treatment of creators behind them in 2013, it stands as noteworthy to look at a major publisher of creator-owned comics that has been a household name for even longer: Dark Horse Comics.

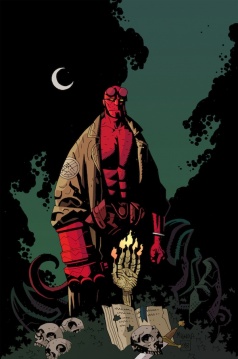

Founded in 1986, Dark Horse is one of the biggest puveyors of creator-owned books and has been for some time, home to a character who is literally just as big as any Marvel or DC character with Hellboy. Hellboy is iconic in every way, and his related line of comics with spin-offs and other media adventures considered is rather diverse (and covered extensively monthly, sometimes even weekly, right here at MC). But the chief difference between Hellboy and other massive character successes that have inspired a franchise is that Hellboy is still 100% creator-owned by the man who brought him to life, Mike Mignola.

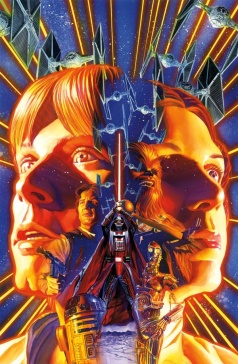

Of course, Dark Horse is also home to many licensed properties. Star Wars comics are found primarily at Dark Horse, alongside other licensed work for Conan comics, Buffy comics and more. Dark Horse has perhaps the biggest even mix of both creator-owned and licensed books across the board, and as such, Dark Horse’s main task as a publisher is to reach an effective balance between what they publish that is strictly creator-owned material and what they publish that is company-owned, as well as how to reconcile the two under their company’s legacy. Dark Horse is not the same as Image, nor is it the same as any other publisher on the market; they have to do what is best for them and the comics and properties they publish.

With that in mind, Editor-In-Chief Scott Allie doesn’t necessarily share the same general idealism of creator-owned comics we’ve previously discussed. “I know a lot of readers pledge their allegiance to creator-ownership, and I appreciate that, since the Mignola books have been such a huge part of my life,” Allie reflects. “But I don’t think most readers are concerned with who owns the material they’re reading, they care about how good a read it is. And I’m not saying I don’t care. I wish to $%&# Joss owned Buffy. But whether we’re doing a creator-owned book like Hellboy or a company-owned book like “The Occultist” or a licensed book like Serenity, we’re trying to bring the same things to it, as much as we can.”

Because ultimately what Dark Horse wants is intrinsic to the story: “A smart story that rewards a close read, good sophisticated art, generally with a very modern feel but a classic approach to storytelling mostly, but not all the time. And above all, a story that reflects a strong creative vision.”

Continued belowThis might seem obvious to some, but it actually reflects a level of refinery and interaction not necessarily present in other aspects of the creator-owned world, where comics are simply published based on the decisions of the creators pending the success of the pitch. Given the different degrees of comics at Dark Horse, the publisher gets much more involved in the process than one might see at a place like Image. As Allie continues, “I pride myself not on my vision, but my ability to create books that accurately represent a strong vision, whether it’s Mignola’s or Joss’s or Robert E Howard’s (RIP).”

It works, and it has worked for over twenty years. As Allie is quick to point out, “We reflect the audience in a unique way and build a library that’s going to appeal to them. Marvel and DC specialize in massive superhero universes that reward loyalty but don’t offer a lot of inroads for new readers. Image is doing great stuff on a pure diet of creator-owned books. But I think readers’ tastes are more eclectic and comprehensive.”

Now — this isn’t to move away from the important aspect of who makes the comics, mind you. It’s simply that Dark Horse views their creators and the aspects of creator-ownership in different angles based on their particular and unique perspective.

So where Image puts the focus on who has come and what they’re bringing, Dark Horse — with all of their licensed properties — tend to publicize a mix of this. “Dark Horse is really focused on the creators, beyond the idea of creator-ownership,” says Allie. “I want Tim Seeley fans to come to Dark Horse, whether it’s for “Ex Sanguine” or “The Occultist,” just like I want Brian Wood fans to come to Dark Horse for “Channel Zero,” “The Massive,” “Star Wars,” “Conan,” etc. And of course Mike Mignola, Joss Whedon, Geof Darrow, and more and more. We build libraries around great worlds and characters, like Star Wars and Hellboy, and great creators, like Joss and Brian.”

As such, when considering their place in the overall landscape for where they are today against the notion of whether creator-owned comics have become trendy, everything about Dark Horse has to be taken under a different thought process. However, looking at the kind of work one can expect from creators at Dark Horse, the answer becomes a bit more clear — and Brian Wood is the perfect example of this.

Wood has quickly made a big name for himself at Dark Horse (in addition to a considerably grand career and popularity from previous work). It started with the re-release of “Channel Zero” in a complete volume, but soon after Wood launched “The Massive” at Dark Horse, his first major comic follow-up to the monumental “DMZ” at Vertigo (thus again sounding the death toll of Vertigo as the chief home for the best in creator-owned comics — and, as Wood has pointed out, “The Massive would’ve been cancelled if it had found a home at Vertigo) . This was later additionally coupled with the announcement Wood would be bringing his renowned creative approach to two massive (pun intended) properties as the new series writer for both “Conan” and “Star Wars,” and one could probably assume that his relationship with Dark Horse is only going to grow greater from here.

But Dark Horse is also conscious that, for some people, it’s more about “Star Wars” than it is just Wood, as well as vice versa, and the same with “Conan.” It’s the sort of balance that other publishers of company-owned comics haven’t quite seemed to figure out the appropriate balance for — but Dark Horse has.

Dark Horse has figured out a way — for them — to balance both how to excite core fans of properties and fans of the creative teams, and the proof is in the pancakes (so to say) with how they treat what is arguably their biggest series: Hellboy. “With the Mignolaverse, Mike doesn’t want to overshadow his collaborators,” Allie notes. “So we don’t do what Dynamite does and put his name in 288pt type above the cowriter and artist. I know in our marketing meetings the conversations revolve heavily around the creators, so I’m surprised if that’s not coming across. With “BPRD Vampire” I think all our promotion revolved around “From the creators of Daytrippers,” and our promotion for the upcoming Occultist series is “From the creators of Revival.””

Continued belowSo what makes 2013 such an exciting time for Dark Horse is that now, more than ever, Dark Horse is becoming open to new projects and creators both known and unknown, putting a massive focus on different kinds of comics (creator-owned or otherwise) that span infinite genres. In fact, the types of books that Dark Horse have begun producing offer up some of the most eclectic on the market from a wide variety of talents and creators; it’s not inherently comparable on the same scale or level of what Image brings, but the same ideal of hosting multiple genres and takes on established tropes is very present in their current publishing line. With a shared universe of superhero characters slowly burgeoning (with things like “Captain Midnight,” “Ghost” and “X”) and a litany of critically acclaimed books like “Black Beetle” or “Mind MGMT” (which we cover extensively here), Dark Horse is making a massive comeback.

“We just won best web comic, with Norton for “Battlepug,” and we won best anthology for “Dark Horse Presents,” which is typically about 90% creator-owned, and which allows us to launch a lot of new creator-owned things.” It’s not hyperbole when I say that “Dark Horse Presents” is perhaps one of the best comics on the market right now. Not only does the book carry with it a massive legacy of creators who have brought industry staples into the anthology, but it remains one of the best places to find and try new creators and concepts month in and month out — including but decidedly not limited to the aforementioned “The Massive.”

As Allie continues, “The advantage of DHP, one of them anyway, is that you get to try things out. And I don’t mean gauge sales potential, because there’s only so much you can determine there. But at the time you’re looking at a pitch, there’s little to say how good the thing will really be. Most of the time. But you hire the guys to do a couple eight pages, and in doing it, they figure out what it is they’re doing (you never really know, as a creator, exactly what a story is until you get inside of it) and you get to see how well it clicks.”

And as an example, Allie points to one of our absolute favorite Dark Horse comics right now, “Resident Alien” by Steve Parkhouse and Pete Hogan. “Resident Alien started as a DHP pitch, and now we keep going with that thing based on how cool the first couple eight pagers were. Would we have said yes to a miniseries on that one? Maybe, but being able to test the waters was a great option, and it’s an important part of keeping DHP around, collecting awards.” And it’s important to note that “Resident Alien” is a book that follows the same publishing methodology as Mignola’s books — that is to say, to exist as an ongoing story but be published in otherwise self-contained minis to allow easy access for new readers. This practice is not only a staple at Dark Horse, but has become an industry recognized and utilized narrative device across all publishers.

So Dark Horse is in many ways a legacy publisher for the world of creator-owned comics. They set a standard in the past of the kind of quality we should expect and the treatment of creators, and they made good on their promise to deliver some of the best in the business. But it’s a legacy that continues to grow and evolve as the company does with it, as they’re not content to sit by on the sidelines and simply watch the revolution happen. Dark Horse is becoming a greater and more active participant in the championing of the creator-owned, and they’re doing it in a way that mixes Image’s idealism and the Big Two’s company-based practices for an end product that is completely viable and absent of the more murkier actions found present elsewhere.

“I think we were soft on launching new creator-owned books for a while there in the darkness of the recession, but we are back,” says Allie. “”Dream Thief,” “The Answer,” “Black Beetle,” “The Victories,” “Mind MGMT,” “The Massive,” “Kiss Me, Satan,” “Clown Fatale” – we’ve launched a lot of new creator-owned books in the last year, and we have a lot more coming soon. I’ll be seeing you in New York, and we’ll have some announcements to talk about there.”

Continued belowWe’re Nobody’s Robot! We’re Nobody’s Monkey!

Now we’ve come to the final section of the article, in which we look at the new kid on the block, Monkeybrain Comics.

Launched in the summer of 2012 by Chris Roberson (fresh off a fracas with DC) and Allison Baker, the indie comic book publisher had one simple focus: to publish only independent comics and to publish them digitally for $0.99 a pop (in almost all cases). While hesitant at first during the initial advent of Comixology, the world of comics has taken leaps and bounds in terms of the digital publishing of books, and Monkeybrain is one of the first publishers to truly angle in on the digital realm as their own.

Since its initial launch, not too much has changed at Monkeybrain — at least not its methodology or intent. Monkeybrain struck a deal for print collections of their comics with Image (there’s that name again!) and IDW this past summer, but their first and main goal still resides in the world of digital publishing, with their line-up of comics being exclusive but never the less frequently expansive towards the creators they work with and the comics they publish. “From the beginning, Monkeybrain Comics has existed primarily to publish the kinds of comics that Allison and I would like to read, and that hasnít changed in the slightest,” said Chris Roberson, co-owner of Monkeybrain Comics. “We like working with creators we like as people and whose work we adore, and I don’t see that changing any time soon!”

Having the publisher primarily be digital also affords unique opportunities to Monkeybrain. “I think one of the main benefits of digital is its flexibility. Our titles aren’t locked into a certain page count, or even a certain release schedule, and so the creators are free to make the individual issues as long or as short as they need to be to tell their stories the way they want,” Roberson explains. “And since we don’t have to worry about print costs and the like at the outset, it means that the creators can continue to do their comics for as long as they want without the looming threat of cancellation, giving the titles the freedom to grow an audience organically over time. And I think that has meant that we have a more eclectic and diverse lineup of comics than youíd generally find elsewhere as a result, since everything that we publish is really a passion project for the creators involved.”

And, of course, Monkeybrain insists on all of their comics being 100% creator-owned. From the names on the cover to the people behind the scenes, Monkeybrain’s policy is that all creators have an equal and shared stake within their book, and its through this that they remain a rather vital proponent in creator-owned comics.

Where Monkeybrain seemingly pales in comparison to the other publishers, however, is in their release schedule. Whereas Marvel and DC dominate the weekly releases and publishers like Image and Dark Horse battle for second place with their 5-10 releases a week (average-ish), Monkeybrain is content with releasing as few books per week as makes sense. “The biggest motivating factor is our desire to give each of our titles the attention they deserve,” Roberson explains. “If we were to release dozens of new titles every week, there’d be the very real likelihood that too many of them would get overlooked and lost. But by limiting ourselves to just two or three titles a week, it means that we can give each of them the kind of care and attention they deserve, both from a production and from a promotional standpoint. And it means we’re not overburdening reviewers or readers with too many things to pay attention to them all.”

So in terms of creator-owned books being trendy, where does Monkeybrain fall? Where do the names of creators fit in in terms of what the company wants to do? “The emphasis with our titles is pretty much equally on the creators as on the content, but we’re less concerned with the commercial marketability of “big names” as we are with people who we like and admire and who we think do fantastic work,” said Roberson. “Some of those people are “bigger” names than others, and some are future superstars in the making. But we’d much rather publish a fantastic comic by talented people we want to work with than a mediocre comic by some jerk who has a proven sales record.”

Continued belowIt’s certainly an interesting stance, and one that seems echoed by the other publishers in different ways — but for Monkeybrain, the comics are primarily the bottom line and everything else is comprised of more or less happy accidents. Where that methodology is inherently fruitful is in the simple fact that what Monkeybrain ostensibly wants to build overall is the same kind of trust inherent at a place like Image: trust in their brand, trust in their selection. While all publishers hand-pick their material, Monkeybrain’s viewpoint is to do so with a blank slate mentality; having an established name in comics won’t hurt, but it’s not the point either, and that the book has made it into Monkeybrain’s line-up should be a good sign of the quality.

So Monkeybrain is in a very different place than the other publishers we’ve looked at in this piece, especially because they’re still so new, but they have the same heart at the center. “Our goal from the beginning was to make our comics available in whatever form readers preferred. Those who want the immediacy and low cost of digital serialization have that available to them on a regular basis, but those who prefer to read in print or to have a collection on the shelf will ultimately have that option, as well,” says Roberson of where Monkeybrain is at today. “And a surprising percentage of readers are doing both, reading the comics in digital form from issue to issue, and then picking up the trade collection when it is available. And still others are reading the trade collections first, and then starting to read the digital serials from that point onwards.”

“Freedom of choice, both in terms of what our creators are able to create and how the readers are able to enjoy it, is the main thing.”

The Future

Five years ago, Robert Kirkman quit working on company-owned comics to pursue creator-owned comics full time, unleashing upon the world his Kirkman Manifesto. In it, he claimed he knew how to fix comics, and to do that would require two simple steps. I’ll quote him exactly here:

Continued belowStep One:

Top creators who want to do creator-owned work band together and give it a shot. I’d certainly love for that to be at Image, but whatever, wherever — if you want to do it, step up and do it. The more people who do it, the easier it’ll be to do. Creators are very important to the current fan base, if it’s done right you could bring a large portion of your audience with you provided you take the plunge and only do creator-owned work. If you give people the option of Spider-Man or your creator-owned book… they’ll choose Spider-Man, that’s something time-tested versus something new. New has to be the only option.

Step Two:

If that results in a mass exodus of creators leaving Marvel and DC, don’t panic guys, I love their books as much as everyone else — nobody wants to hurt them in the process. Look at it like an opportunity, that’s the time for Marvel and DC to step up the plate and make their comics viable for a whole new generation. Less continuity, more accessible stories — not made for kids, but appropriate for kids. Books that would appeal to everyone still reading comics, but would also appeal to the average 13 year old too. There are a wealth of talented creators who haven’t yet reached a level where they can sell books on their own — they can do awesome work for the companies and be happy doing it.

What that could lead to:

A comic industry where there are more original comics, so there’s more new ideas, more creator-owned books by totally awesome guys that are selling a ton of books. Those books are mature and complex and appeal to our aging audience that I count myself among who are keeping this business alive. And we also have a revitalized Marvel and DC who are selling comics to a much wider audience than ever before. And that audience, as they age, may get turned on to some awesome creator-owned work eventually. So everyone is happy.

I’m not saying it would be as simple as all that, I’m just saying this “could” work and that there are enough smart people working in comics today that it could probably happen. The problem as I see it, is that Marvel and DC are currently very successful with the audience they have now, “us” and we’re all happy with the comics they’re producing… because they’re all mostly awesome. But as we age, we die, so we’re not going to be around forever and so if comics continue to age with us, they will die along with us and that’s not something I think any of us want.

Upon the release of his statements, it admittedly caused a fair bit of debate and even controversy. Some prominent creators found the notion ridiculous, and that there was no way this could work.

But five years later, it turns out Kirkman predicted the whole thing. Top creators who want to do creator-owned work have banded together to give it a shot, and it’s resulting in a exodus of a kind from the Big Two. They’re bringing their audience with them to the creator-owned comics and essentially bringing Kirkman’s vision of A Better Future to light.

It’s rather impressive, really. And here I had said that I didn’t think there was a Nostradamus of comic books! And hey, Kirkman has turned out to be one of the most successful creators of our time, with a hit TV show, several books on the market and an imprint he runs. He’s very much on top of the world, and he worked damn hard to get to that place.

That said, this doesn’t mean that this isn’t a trend, nor does it mean that creator-owned comics haven’t become trendy. That’s simply a facet of it, if a small one. Creator-owned books have certainly seen a rise in prominence over the last few years and that escalation in importance isn’t going to stop anytime soon, especially if big name creators continue to choose working on books their own.

So really, seeing the latest Image Expo and all the names that have chosen to work with them is — in a weird, weird way — essentially our destiny. Maybe that’s too lofty a word, but if Kirkman is right (and I believe the future t-shirt sales of “Kirkman was Right” will be the deciding factor on that one) then the direction that comics are currently headed in is literally what is best for comics overall — and that’s absolutely nothing to scoff at.

(And a big thank you/hat tip to Colin Bell for reminding me of the Manifesto.)