The new Peanuts movie opens Friday, November 6, from 20th Century Fox and Blue Sky Studios. The Snoopy Industrial Complex, perennially active, has kicked into high gear, circulating the newly-3D Charlie Brown and the Gang on Fox NFL Sunday, big box store ads, and all over social media in the form of Peanutized avatars of every last one of us.

The Grumpy Old Man in me fears this caffeinated and CGI-ed Peanuts bursting from the trailers will rip my family from our 1965-paced quietude and thrust us into contemporary short-attention-spantertainment. But I can’t be cynical about it. My family and I are hyped, and we’ll be lined up at a theater on Friday for the opening.

Because I can’t front. I owe Peanuts a lot. So this column is my appreciation for the gifts it’s given me, the treasures of reading Charles Schulz’s strip as a grown-up comic reader, as a father, and as a cultural critic.

See, despite my childhood among stacks of Sunday funnies, the gnarled Calvin & Hobbes collections, the crinkle-edged reprints of old Dick Tracy and Pogo, tottering piles of Li’l Abner, I have to admit I never used to like Peanuts. Flat-out skipped the strip. Stuck my tongue out at the ubiquitous merchandising. Dismayed at occasional forays into reading Snoopy only confirming a suspicion that the humor was stale and pedestrian, unfunnied by overexposure, like too many Garfield Mondays, like too much Dilbert cubicle wit.

Until. Until. About a decade ago, on a family vacation, we wandered to Santa Rosa, a North Bay town on the edges of Napa, erstwhile neighborhood of Charles Schulz and now home to the cleanly modern Charles Schulz Museum and Research Center. Walking among the Comic-strip Deco exhibits, the replica of Schulz’s studio preserved in 1980s woodgrain amber, and most of all, the exhibits of original art, the gentle Turgenev-like drama of the characters enfolded me, unthreateningly, like a Saturday afternoon among the shady trees I’d long lost to the interstate and the internet.

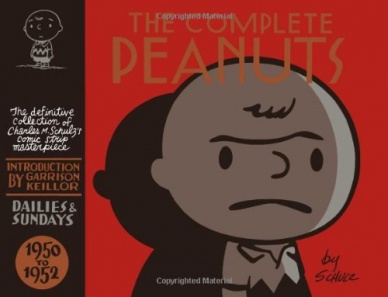

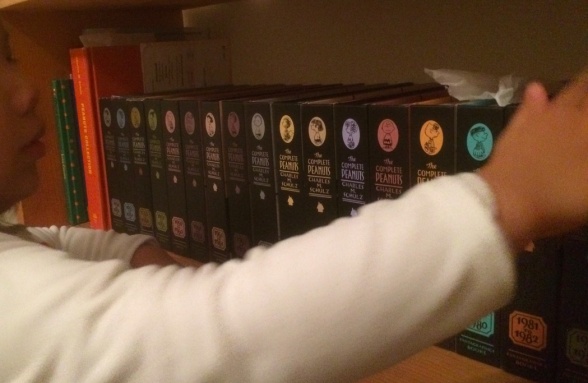

By divine appointment, the Schulz Museum Gift Shop happened to discount the first volume of the Fantagraphics collection of The Complete Peanuts (currently on sale and part of this Humble Bundle). On a lark, I bought it. “1950-1952,” said the Seth-designed cover, sleeved in nostalgia, an image of the oddly off-model (or more accurately, pre-model) Charlie grimacing with all the pent-up disappointment of every coiled, slighted American child.

I became entranced. I read all two years in one sitting, irresistibly smiling the whole way. Hastily I ordered the rest, pre-ordered each volume as Fantagraphics released them, marched through the last half of the 20th century with Schulz, day by inky day.

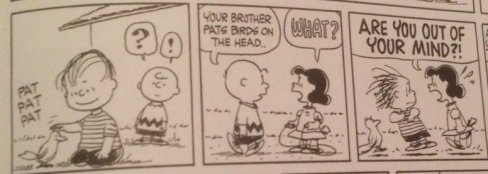

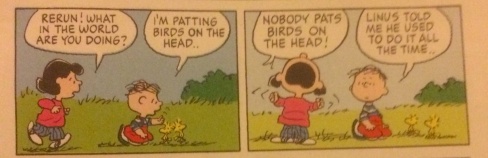

All the jokes I never got (or never thought were funny) became uproarious, earned, canny. I came to understand that, contrary to the sense all the pervasive licensed products give you of fungible and contextless boilerplates, one cannot fully appreciate Peanuts without bathing in the birdbath of its long history, reading it in the context of its remarkable run. Punchlines call back weeks, sometimes months, sometimes years into the past, when artfully laid ironies and finely observed ridiculum first dawned on the Peanuts panel and then waited with bated breath to pounce again, slow-roasted to perfection. Schulz’s humor was not haphazard, and neither did he sloppily nor cheaply construct the vitality and personalities of his comic strip children.

And I’ll spare you the personal details, but Violet, Schroeder, Marcie, and the whole crew wended their way around my imagination at a time in my latter 20s when the breakneck pace of high ambitions could’ve crushed me under its momentum. Instead, I fled to Charlie Brown’s pusillanimous frown, Lucy’s pugnacious fuss-budgeting, Linus’s preternatural Scriptural wisdom, and Pigpen’s transcendental filth. In a funny way, Peanuts saved me.

So in honor of the movie’s release, in humble hope that some of the Hollywood hype will charm a few souls into the leisurely pleasures of the newspaper strips, and in a modest hats-off to “Sparky” Schulz’s forthcoming birthday (he’d be 93 on November 26th), here are six-and-a-half pleasures from my reading six-and-a-half decades of Peanuts reprinted (Spoiler Alert: There’s no such thing as a Spoiler when it comes to Peanuts.)

Continued below- The Early Strips Were Almost a Different Comic.

Not unrecognizably different, mind you. For many seminal newspaper comics, somewhere along the daily hustle, a cartoonist would find that strange twist that catapulted the strip from topical to timeless. Drawn + Quarterly and Chris Ware’s collection project of Gasoline Alley, renamed Walt and Skeezix, captures such a turn when, with the 1922 arrival of an abandoned baby on Walt’s doorstep, a daily strip about an alley of gearheads became a majestic family chronicle of quotidian beauty.

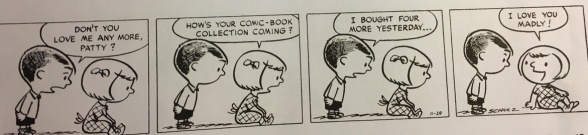

Schulz had a formula that worked from day one: cute kids’ abrupt cruelty. Early Peanuts humor exploited the gap between our expectations of children’s round-headed sweetness and their actual narcissism and sheer venality. At the outset, Shermy and Patty (not that Patty, the previous Patty) got as much screen time as good ol’ despised Charlie Brown. They represented the prime punchline of the early strips: not the later, well-defined characters like Peppermint Patty stewing for decades in the juices of their eccentricity, but like other Patty, archetypes of mid-American regularness, with a bite!

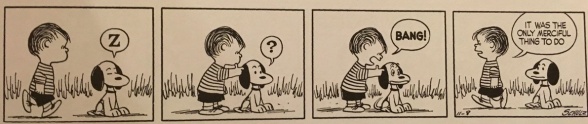

Which is why they virtually disappear from the foreground within a decade. By the late 1950’s, Schulz had literally given birth to (in the comics sense of “literal”) a key turn that made Peanuts transcend the Katzenjammer Kids or Family Circus. The seeds of this discovery are there in the first strip, in that Charlie frown. Turns out, the soul of the strip would not be the quick funny of the sharp insult, but in the pathos of the insatiable hope of being something more. Lucy steals the spotlight from Violet as an infant by dint of her hilarious self-exaltation. Linus is Frank Lloyd Wright with blocks before he can even speak a word of the precocious philosophical savant he’ll become. Even 1950’s Snoopy, pre-Flying Ace, pre-walking on hind legs, pre-typewriter, seems to twitch with profound yearning to be so much more than a lapdog. And Chuck… good grief, you blockhead, when you stop hoping, the world stops turning.

Schulz found this bent of his humor and humaneness fairly early. But until it became his focal mood around the mid-‘50s, it’s fascinating to watch a genius still finding his voice. This Fantagraphics FCBD “Unseen Peanuts” mini-collection captures these hiccups well, gathering some of the quirkier (and sometimes darker) fluctuations and aberrations of those early years. But in the context of one of the most refined and unstinting marathons of American arts, the germs of that early discovery of what would be kept and what would be subtly shed are fascinating to read.

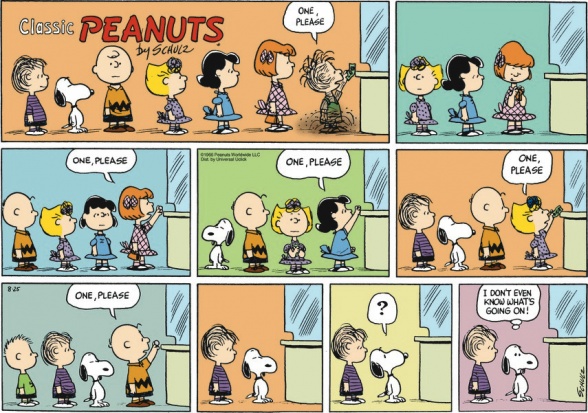

- The Treasures Only Time Can Produce. And Pay Off.

One of those gags I shrugged at until my Peanuts come-to-Jesus moment was the Charlie-Lucy-Football Yank. My child brain grasped that ineluctable pattern of cajolery-trickery-flyupsidedownery earlier than it even grasped the cycling of the seasons. Maybe the juvenile mind is developmentally incapable of contemplating the wry comedy of repeated futility, but to be franklin, I just didn’t get it.

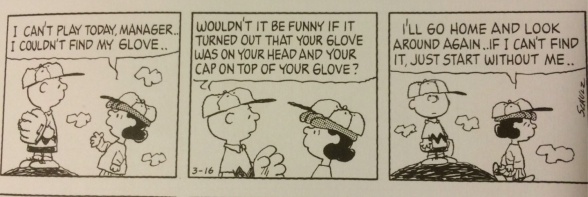

What reading Peanuts over its fifty year span, from Charlie’s very first failed punt to his last gravity-defying loop (or was it?), brought home to me was that Charles Schulz knew how to nurse a joke. As this Slate piece by Eric Schulmiller documents, the origins of the gag followed a well-laid foundation of football frustrations, presaged by Lucy’s own mania, and evolves through annual iterations whose new wrinkles were constant surprises. And for all the play that gag gets, he only used it once a year. For about forty-six years.

Ditto the Great Pumpkin. And Marcie calling Peppermint Patty, “Sir.” And the baseball line drives that knock Chuck’s socks (and usually his entire uniform) off. The first time, zany and spontaneous. Each time Schulz goes back to the well, it’s a marvel of calendrical comic timing.

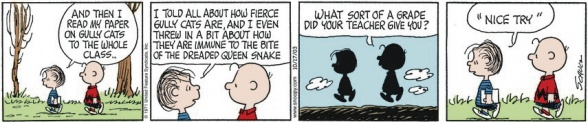

No wonder I didn’t laugh at the 1990s fourth-panel joke built on a Linus remark about “Gully Cats.” I had not yet encountered the 1971 sequence where Linus the wunderkind/naïf concocts an oral report where he contrasts the fierce Mountain Lion with the even fiercer (and fabricated) Gully Cat. Say the words “Gully Cat” with the unquenchable earnestness of Linus’ face in mind, and you can’t help but laugh at the absurdity. And then you find, sprinkled throughout the decades proceeding, like an herb you once tasted and forgot existed until it reignites that mirth in your mouth, every now and then, another mention of “Gully Cats.”

Continued below

Live only in the present and the jokes seem repetitious or random. Walk through the strip’s history and they unfold and pay off marvelously.

- Teaching My Kid the Word “Stupid.” (And Many Other Words.)

There can be no doubt that part of Peanuts‘ staying power is its universalism, its all-ages appeal. Because of the stringent self-censorship of the newspaper syndicates, you’d think more newspaper comics would have a similar universality, but on closer inspection, from Cathy to Far Side, from Terry and the Pirates to Beetle Bailey, none quite reside in that same pocket of cross-age and cross-demographic reach like Peanuts. Chalk it up to deceptive simplicity that belies profundity, Schulz’s aw-shucks Midwesternism combined with his West Coast open-mindedness.

My newborn daughter came home to a nursery already decked out in Peanutphrenalia. At three, amid all the Halloween Disney princesses in her preschool, she opted for her costume to be Linus Van Pelt. And like Linus, she’s the sort of unnaturally early literacy whiz you might expect from the only child of two helicopter English teacher parents. We’ve enrolled her unwittingly in a research experiment: What happens when you raise your child on a steady diet of Peanuts?

For one, she learns to call things “stupid,” a mild swear her genteel parents (ha!) would never utter in her presence. She learns to make sourpuss faces, mope around the house as if “Christmastime is Here” was her life soundtrack, and fret prematurely that no one would write her a Valentine.

But oh, the wonderful things. Comics like Peanuts (combined with a robust outside-of-comic-books life, of course) have a way of training children to attend to faces, to even the most minute cues of satisfaction, agitation, despair, eagerness, nervousness, from which we weave our sense of the human emotional fabric around us, from which we gather our sensitivities to the important things our caretakers want to direct our attentions toward. (Scholarly nerds may like to know, I’m referring to this kind of research about how children learn language and culture.)

I’m grateful even for the utterances of words like “stupid,” even for the examples of naked cruelty she reads in the strip. Violet and Patty’s ruthless taunts. Schroeder’s parries of Lucy’s affections. Snoopy, jilted at the altar by his flighty fiancée and his brother Spike, after himself abandoning his guard-dog post to Charlie in an unforgettable 1977 sequence. All these examples of bigfoot meanness, unrequited infatuation, and ached longing have supplied the emotional equipment for a young girl to find her way to bravery, resilience, sometimes even a matter-of-factness about life’s vicissitudes. Yes, I’m saying, Peanuts has taught my kid the dark underbelly of life.

To quote my four year old, verbatim, “”Let’s say I’m feeling a little a bit overwhelmed and I don’t know how to explain it. Like, when a Peanuts character touches my mind, then I feel the feeling that they feel most of the time. It helps me know I’m normal.”

But also, tack on the lesson that the same dance move done over and over again with passion CAN constitute a viable party routine. And the security of a warm puppy, or a blanket, or the gentle side of a sibling. Oh, and words! Before we had any chance to pressure or prod, she sat silently, for hours, combining context and comprehension to find her own way around what reading teachers call decoding. Schulz gets no small credit as her first reading teacher.

- It’s Too Commercial!

Another byproduct of being a Peanuts-obsessed household is discovering the endless repository of merchandise available EVERYWHERE. I grew up with the Puritanical sanctity of Calvin & Hobbes’ Bill Watterson, who forswore all merchandising of his comic strip creations in spite of his admiration for Schulz, at least in part because of how cheapened Peanuts seemed to become by the Snoopy Air Fresheners, Charlie Brown theme parks, and life insurance peddling. The pervasive product hawking was a turnoff, especially with the spirit of “A Charlie Brown Christmas” ringing in your conscience that “even my own dog has gone commercial!” (We own at least six adaptations of the “Charlie Brown Christmas”— noisy children’s books, iPad apps, dolls that talk— that all repeat that ironic lament).

Continued belowYou hate it and you love it. It’s like sports fandom. Get wrapped up in the trappings and the hype, and you’re left feeling the same vapidity that drags Charlie Brown to his meager Christmas tree.

But return to the humble strip, to Marcie and Peppermint Patty sitting silhouetted against the trunk of a tree, to Snoopy’s joie-de-ice-skating, to Schroeder before a fresh sheet of Beethoven, to the ennui of summer camp…and the accretion of the marketing millions has a way of fading into the background.

Plus, y’know, stuff is cheap on eBay when there’s so much of it.

4.5. Enormous Cultural Impact, Vast Secondary Literature.

(This is my half-point, because this one and the last are not about the strip itself….)

Moneymaking brand-dilution aside, becoming a Peanuts appreciator is entering the waters of a huge, highly devoted, and often erudite fandom. Schulz’s four-panel (and in time, three-panel, a concession to the syndicates that his fellow cartoonists bemoaned) meditations have had enormous worldwide influence on comics and cartooning, spawned a vast secondary literature from controversial research to theological reflection, and inspired tributes from a huge array of comics creators and other artists and celebrities, such as the Complete Peanuts introductions from the likes of Jonathan Franzen and Billie Jean King, or the recent KaBoom! Peanuts: A Tribute to Charles M. Schulz. And of course, there’s the parodies and riffs, furnishing us with the existential dread of Peanuts missing its final panel, Peanuts with Smiths lyrics, and R. Sikoryak’s “Good Ol’ Gregor Brown.” It’s a trove of geekery, and you will not run out of companion texts.

- A Refined Line Becomes a Beautifully Wobbly Line

A video that plays on repeat in the Schulz Museum describes how Schulz’s assured and seemingly effortless ink line flowing from his Esterbrook nibs became wobblier in the strip’s latter decades as he aged, especially after suffering a stroke. Rather than folding up shop, Schulz famously embraced his shake, enfolded it into the unmistakeable character of his drawing line. It was a line so integral to the life of his creations that Blue Sky Studios “broke the system” of the usual computer animation tools to capture his genius for the new movie.

Initially, the 1950s Schulz is still toying with the realistic perspective and detailed rendering that would actually stiffen his characters and stifle their spirits a bit. At the peak of his prowess, maybe the mid-60s to the mid-70s, Schulz is a paragon of cartooning elasticity, rhythm, proportion, and effect, matching his defined but unpredictable wit with a remarkably consistent artistic elegance.

Those were the years Charlie, Linus, Lucy, Schroeder, Sally, and the gang became inimitably Schulz’s. Anyone who’s ever tried to draw the odd cranium and peculiar hair-pattern of Linus’s head without visual reference, and then watched the ease with which Schulz materialized those distinctive curves, will grasp the sense in which those characters seemed to have lived and breathed in their creator’s imagination and fingers. One of the more endearing entries in the aforementioned KaBoom! tribute book is Hilary Price’s story of meeting Schulz in person and catching fleeting glimpses of all his characters in the man himself. Sometimes, it’s hard to know where the Peanuts kids end and Charles Schulz begins.

But as the whole run of Complete Peanuts volumes sits in front of us for our evening reading, despite knowing the peak years reside in the middle of the shelf, I find myself drawn to the later decades, and the Schulz and Peanuts I find there. I find it so fitting that a comic strip so wrapped up in embracing the wobbles of these spectacularly flawed and utterly lovable children would seamlessly integrate the “flaws” of its creator into its artistry. By the 80s, the global Snoopy, the jagged yellow shirt, and the many resuscitated gags could already claim their saturation in the world’s culture, in the Winter Olympics, on Asian lunchboxes. Creativity became cleverness and then became cliché. It’s in these decades where some critics point to stretches of the strip where Schulz seems to rest on his laurels a bit, one too many Red Baron rehashes, Peppermint Patty’s near-narcoleptic academic career getting a little overdrawn, diminishing returns on proliferating TV specials. (Although this one with Linus in-line skating is absolutely priceless, if only for how hilariously off-model and of-the-times it is.)

Continued below

To those critics who knock the 80s and 90s Schulz, I don’t have many sharp retorts. After all, those were the days when, as a kid, I had little patience for Peanuts. I’d guess, actually, Schulz had run out of energy or patience for sharp retorts himself by that point. Seems like the kids lost some of their vim, and the humor lost some of its edge.

But as an adult reader, treating the strip’s fifty years like a massive novel, I find myself more sympathetic to where he chose to dwell in those years, attracted to the slow grace of figure-skating, much more indulgent of afternoon chats perched on a brick wall with a good friend, more enamored with the sanctity of a yearly ritual grieving at the empty Valentine’s mailbox. Even Snoopy’s inane role-playing as a vulture or disaffected undergraduate suddenly sounds a lot like the cheesy dad jokes I make around the house. Call me boring. Call Schulz old. But you can’t call it disingenuous. Up through the very last strip, Peanuts the comic strip maintains an integrity to the inner neighborhood of children inhabiting Schulz, and however wobbly, there’s beauty there.

- Even Better in Reruns.

I don’t mean to make it sound like the latter decades of the strip are only for fuddy-duddies, or old people who use words like fuddy-duddies. (For the record, I’m only as old as Schulz was in his sixth year of Peanuts.) Charles Schulz worked on the strip up through the last year or so of his life, and I find especially those final years– to date, the Fantagraphics archivals are caught up to 1998, the strip ended in 2000, and other reprints of the last years are easy to find– still sometimes laugh-out-loud funny, still likably off-kilter.

And despite hailing from the Truman administration, the comic strip’s master still knew how to inject some youthfulness into the Peanuts neighborhood. I’m not talking about the sad truth that, even under Sparky’s watch, Snoopy would probably be doing the Whip/Nae Nae on a commercial right now (He probably is. I’m too scared to Google it.) I mean that Schulz knew how to retain that timeless sort of wonder and whimsy, even up to the end.

Rerun is the best exemplar of this. He is born off-panel in the 70s, Lucy’s karmic comeuppance for exiling her little brother in a severe sibling conflagration. He appears rarely for two decades, only occasionally referenced and with only the rarest back-of-mom’s-bike gag, presumably still gestating in Schulz’s creative incubator. Then, in the strip’s last handful of years, he comes roaring into the spotlight, not unlike Lucy in the early 50s and Peppermint Patty in the 70s. By Peanuts 2000, he appears as much as any other lead.

The understructures of the Rerun jokes are familiar: he turns every drawing assignment in his pre-school class into a crayon maelstrom, he can’t ever get the basketball to graze the rim, he grips handlebars in mortal terror as his mom tears through the town or the grocery store. Rerun seems like an outlet for fresh takes on Schulz’s old saws.

But at this late date, with such a long corpus under his belt, it’s proof of Schulz’s vitality that he finds such vibrancy in the starry-eyed wonder and slow-dawning cynicism of a young kid again. Rerun reminds readers of the eternal child that even the mature Schulz guards in his cartooning spirit.

He also gets to give maybe Schulz’s last words in the strip about comics. It’s the second-to-last Sunday (at this point, it’s only Sundays), not counting February 13th’s farewell letter strip. Rerun and his pony-tailed classmate are assigned to paint flowers, but Rerun is defiantly working on his “underground comics” featuring “Billie Jean King and Daffy Duck throwing Long John Silver off the pirate ship.” Among Rerun’s “big plans for my work” are “consecutively numbered limited edition prints,” “accompanied by a certificate of authentication,” he reports to his teacher as he shows off his page, as aspirational and hapless as any Peanuts character ever. It seems a little like Schulz’s own sly wink to the ludicrous side of his half-century enterprise of comics making and comics marketing.

Continued belowBut his Rerun stands before not an adoring public, rather an unseen teacher behind a grand desk and penholder. In the last two panels, he says, “Yes, ma’am.. I understand..” to her off-panel response to his work, which we imagine sounding like a disapproving trombone.

And then, returned to his drawing table, his classmate asks, “What did she say?” and Rerun replies, “She said today we’re painting flowers.”

For all the high art that Schulz created, an art inestimably legitimized through his genius and massive influence, he does not forget that comics are the art form we secretly make, we can’t help but love, we dreamers and ne’er-do-wells, when we were supposed to be doing the assignment to paint flowers.