Ah, February is ending today, and you know what that means: time for the second installment of 365 Days of Cerebus, my column where I read all 300 issues of “Cerebus” over the years and take time out each month to write my thoughts down to share with you. Maybe I’ll say something insightful. Maybe I’ll just ramble. Either way, it’s an endeavor.

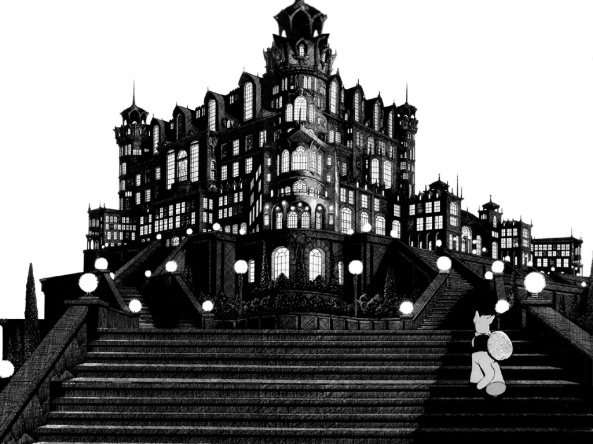

When you’re done admiring Gerhard’s amazing work illustrating the Regency Hotel in the above wraparound cover image, look down below for some thoughts on “High Society.”

The first thing to make note about “High Society,” and is something that can only really be discussed with this book, is the digital transfer – which is absolutely great. Those of you who participated in the digital Cerebus Kickstarter were rewarded with links to high resolution transfers of every issue, and the entire book can also be found on ComiXology (with issue #1 online for free). It’s quite staggering, really, going from a phonebook that has been worn down by the years to a digital version, because you forget that at one point these pages were supposed to be black and white (see: below), not blackish hues and mustard yellow (see: below a bit further, or click here). It’s akin to seeing an older film get an HD Blu-ray re-release through something like the Criterion Collection, and while not all older films inherently need to be given shiny new coats so you can see the actor’s wrinkles (there is a certain charm there), having these versions of “Cerebus” that are accessible and crisp in terms of quality is – if nothing else – a rather great talking point for the pro-digital. And while some remastered comics enhance various aspects throughout the process, it’s nice to see such a clear version of this comic exist that is ostensibly unaltered, giving us all of Sim’s work as it was originally produced – just, you know, on a screen.

Not only that, but reading “Cerebus” in ComiXology offers up a different experience in general. I don’t particularly subscribe to the idea that comics need to be anything more than sequentially display artwork in a readable narrative, but the additions that ComiXology typically brings to the table are all well on display with “High Society.” The Guided View option really adds to the read, and it actually plays off a bit like the guided comic style Mark Waid is using with his Thrillbent digital comics. Each digital copy (at least the ones that I looked at) also comes jam-packed with extras about the development of the series, differing from the back-matter “Cerebus” typically came with during its original release, and it is a pretty great deal for people looking to rediscover, reinvest or visit the world of Cerebus for the first time. So if you’re on the fence about digital comics, “Cerebus” #26 (aka v2 #1) is not a bad place to start.

I do not, however, have that many comments to make about the audio/video editions of “High Society,” having only really bothered to watch a sporadic few. It’s an entertaining little endeavor for sure, albeit something that has been done “better” by companies with bigger production value, and for my preference it doesn’t get much better than just reading the book. That said, #46 (or v2 #21), the issue where Sim brings Chico Marx in for an issue focusing on a dialogue between Lord Julius (Groucho) and Cerebus, is kind of great with the audio, if only to hear the semi-impersonations (which is basically just Sim doing Marx inflections in addition to a Cerebus grumble). That and the public domain muzak in use.

But that’s just one modern aspect of the book, and one that’s really only relevant to a certain audience. Let’s talk about the book itself, now.

“High Society” is a rather strikingly different book from “Cerebus.” His past as a roaming barbarian is all but abandoned, cropping up only here and there as Cerebus changes from a wandering warrior for hire into that of an aspiring politician. There had been some aspects of this present in the first book, particularly when Lord Julius was introduced, but only to a slight extent; here it’s the main course of action, and Cerebus makes for the perfect operator for all of Sim’s satire. See, Cerebus’ main motivation present within the book is that of greed – he cares very little for the lives of most others, seeking only to better himself and his place in the world. When a cushy lifestyle is presented to him, Cerebus essentially leaps at the opportunity, eventually driven by sheer vanity to complete the task of becoming the prime minister. It’s a lot darker than the previous volume, definitely more tongue-in-cheek and it very much represents Sim’s growth as a storyteller from someone telling a goofy story about a warrior Aardvark to a book where Sim uses Cerebus’ inherent silly outsider nature to offer up not-too-subtle commentary on the skewed political system of the 1980s (although we’ll get more into that soon).

Continued below

However, one thing that is very noticeable about “High Society” more so than the first volume is the issue of pacing. With “Cerebus,” a lot of the book was essentially one-and-done adventures of barbarian antics, with Cerebus the Aardvark moving from location to location and meeting a variety of individuals. Yes, some stories carried over, but for a large portion of that series, you can read it alone without too much knowledge of what came before. This leads to a lot of hit and miss examples of storytelling, where some issues read easier than others, although it’s all generally quite great. “High Society,” on the other hand, is very much a book where everything flows into one another in a more typical fashion to your average comic, and towards the end it seems like Sim loses his steam a bit. It’s a dense political satire that shows the rise and fall of Cerebus in office at Iest and over half of the story is dedicated to that, but once he takes office the Six Crises stories kicks off, it’s done so in a way that is decidedly less engaging. The campaign is a great satire towards the political machine that’s still applicable to the modern day political system (Black Mirror just featured a similar satire with “The Waldo Moment”), whereas Six Crises is so densely placed within the world that Cerebus takes place in that some of the story seems overly forced to wrap up the “High Society” story arc, rather than really allow Cerebus time to do much with his power in office.

This isn’t to say that a serious story in this world isn’t worthwhile, mind you, as we know that the book will take a darker turn later into the series. It’s just a matter of balance; Sim seems to front-load the book with material that actively engages you with Cerebus’ campaign and related power struggle against characters both old (Lord Julius and Elrod make great returns, even if I didn’t like Elrod much in the first book) and new alike, so when Cerebus takes office a lot of that initial energy is seemingly lost. Cerebus begins essentially battling against figures and names, making for a dense read focused on internal politics and the emotional toll it takes on Cerebus, and it’s clear that the sequence is done in a relatively less tongue-in-cheek manner to the rest of the book, which doesn’t particularly help its case, especially in situations where any assumed reference isn’t clear or is otherwise potentially currently antiquated.

Yet the astonishing thing is that “High Society” overall really isn’t all that dated. In fact, a very easy parallel to make would be looking at Cerebus’ campaign to Obama’s first campaign for office, at least in terms of Cerebus’ platform representing everything the people wanted (against a goat), yet when he finally got to office his attitude seemingly changed and nothing necessarily got better due to the pit dug before Cerebus took office. It’s one of those weird little “life imitating art” things that’s only visible in hindsight, but it’s interesting none the less. Granted, Cerebus’ goals are relatively disengenuous, as he’s doing this all for himself rather than for anyone else, but it’s never not impressive how Sim has managed to make the book not excessively dated with its subject matter given how out-of-date these things can often become. It’s one of Cerebus’ many overall strengths; there are certainly some things lost in the sands of time, but the repetitive nature of the cultures Sim frequently pokes fun at does allow the book to stay relevant to modern day issues during a 2013 reading.

So to that extent, time is an important thing to consider that definitely factors into the read of the book. What Sim was satirizing is over 20 years old at this point, and the historical context of Cerebus is only so important to the overall read (unlike something like “A Modest Proposal,” which usually comes with a disclaimer explaining things for today’s audiences). It’s something that’s neither here nor there, though; “High Society” can be read without getting any of the references just fine, and knowing about Moon Knight and Bill Sienkiewicz’s work won’t ostensibly increase the enjoyability of Captain Cockroach’s return as Moon Roach (although it doesn’t hurt). I’m sure a more accurate or annotated reading of the material could potentially provide or a more intense overview of the work, but the openly applicable nature of “High Society” and it’s humorous view of politics in a general sense is just as relevant as anything someone like Charlie Brooker could say in a Weekly wipe, for example, which is decidedly more pointed.

Continued below

Of course, politics isn’t the only thing skewered in the book. “High Society” does indeed take a very large jab at high society, both in terms of the political aspect of it and the cultural/snobbery aspect of it, and Sim presents a biting satire similar to Terry Gilliam’s in Brazil and its recurring 27B-6 gag.Yet in addition to this, Sim uses these twenty-five issues to mock a number of things, including comic culture and popular heroes of the time (Moon Knight, Hulk and Spider-Man all get a good lashing) as well as convention culture and his role as an artist. There’s a rather amusing sequence in which Cerebus is called upon to draw sketches for the rich snobs he seeks money from, but is undercut by Elrod’s bunny drawings for hilarious results that builds the rivalry between the two characters further. Some of the most amusing sequences find Cerebus on panels with Lord Julius for the seemingly impromptu Petuniacon, and the scenes poke fun at (and remain entirely relevant via a modern scope to) question and answer panels found at comic conventions, among others. It’s also debatable that Sim turned a satiric eye to romance in comics as Jaka returns, solidifying her role as Cerebus’ love interest from a single previous appearance, although its one done with less humor and more light commentary towards the strange and impractical nature of it all (and the role of women in the book will be discussed at the more obvious juncture).

The craftmanship that goes into the issues within this arc is also pretty stunning as well, and it’s amazing to see the work that Sim was doing in comics two decades ago that today are lauded as modern innovations. For example, a recent issue of “Batman” (#5 by Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo) required readers to rotate the comics as Batman traveled down a maze; “Cerebus” #49 features a drunk Cerebus stumbling through the events of the issue while readers are required to rotate the comic in order to follow him along in his disorienting journey. There are quite a few examples of this forward-thinking storytelling throughout in terms of the narrative technique that Sim employs, including how well the book transforms with Guided View, as mentioned earlier. It’s also of note that “High Society” is where Sim begins balancing prose portions into the story (whether as a transcription from an event or an excerpt from a non-fiction novel) which will be more recurring later, and while I don’t think it fair to credit Sim with the origination of this idea or any of the other tricks of the trade (possible, but I’ve not researched it to confirm either way), it’s never the less still impressive to see how much creativity Sim was using in these books that we somewhat take for granted in today’s modern comic-reading culture. Not to knock “Batman,” but the way that Sim utilizes the rotating book technique is certainly much more interesting, and a touch less stunt-y (although I’ll admit I enjoyed the tactic when I read the issue).

Another interesting technique that Sim employs is that, starting with issue #44 (apparently known as “the Wuffa Wuffa” issue) and up to the end, the book has to be held sideways to be read, a 90° rotation from the standard. While I’m not sure if there was any larger reason for this beyond a storytelling device, rotating the book to give it a widescreen approach is a fantastic narrative tool (again, something that would be emulated by later comics like “Sandman,” “Promethea” and Marvel’s 2001 Annuals) which Sim then uses on a number of occasions for enhanced visual storytelling in terms of the flow from panel to panel. Cerebus himself is a bit of a cartoon, and while the book is hardly cartoon-y this does allow Sim to play up Cerebus’ nature within the scope of the book, with issue #44 alone acting as a pretty great example of this, chronicling Cerebus’ trek through snow with the one man whose vote he needs, which results in the above fantastic visual gag, among others.

So in terms of comparing “High Society” with its predecessor, it’s a rather large mixed bag. The book takes on an entirely different attitude throughout the issues, and while it does keep its humor (although to a lesser extent than before), it’s not that conceptually different. If anything, it’s like having watched “Bananas” before a viewing of “Manhattan,” where the humor and parody is still there but on a more refined and thoughtful scale. The books in contrast offer up two decidedly different portraits of Sim as a creator, though, as “High Society” shows him generally taking more risks in his exploration of the medium and the opportunities it affords him. It’s essentially a book that offers a more specific look at what we can expect to see from Cerebus in the future: a thought-provoking and humorous outlet for Sim’s creativity and occasional real world frustration where the only limitation is the page count.

Continued belowStill, it’s never not endearing – no matter how many times I or you view the work – to see how well “High Society” holds up nearly twenty years after its initial release – whether that be from “Cerebus” #26 in 1981 or the first phone book collection in 1986. And considering what is to come in “Church & State” — well, we’ll get to that next month. Half of it, anyway.

If you’d like to join me in reading the series throughout the year, here is the breakdown I plan to (try and) follow for the rest of the year in order to give me both time to read, digest and write about each volume. We can make a Book Club thing out of it.

- January – CEREBUS (1-25)

- February – HIGH SOCIETY (26-50)

- March – CHURCH AND STATE I and part of Cerebus Number Zero (51 – 80)

- April – CHURCH AND STATE II (81-111)

- May – JAKA’S STORY and part of Cerebus Number Zero (112-138)

- June – MELMOTH and FLIGHT and WOMEN (139-174)

- July – READS and MINDS (175-200)

- August – GUYS and RICK’s STORY (201-231)

- September – GOING HOME (232-250)

- October – FORM AND VOID (251 – 265)

- November – LATTER DAYS (266-288)

- December – THE LAST DAY (289-300)

If you read at least a single issue/chapter of the book every day during the next month, you should be able to keep up the pace with no trouble at all. And if you haven’t seen it yet, Comixology has all of ‘High Society’ online now, with the first issue of the book available for free.

I welcome all discussion in the comment section, but please keep it to the book in question.