There aren’t many people who would label Dark Horse as a small publisher today, but it was once upon a time. Unlike Image, which debuted with instantly top selling books, it took a few years for Dark Horse to rise through the ranks and become one of the five biggest publishers in the comic industry. How did it get so successful, and could its strategy be copied by a new company today?

The story begins in 1980, when Mike Richardson used a credit card to open a comic shop called Pegasus Books in Bend, Oregon. He had an art degree and had worked as a commercial artist, but no real business experience. When he first opened Pegasus, everyone but his wife thought he was nuts. No doubt about it, the store did have a rough start – the first day’s sales were $8.37. Fortunately things improved quickly and, five years later, the store had multiple locations throughout Oregon and Washington.

Through the course of everyday business Richardson befriended a large number of illustrators and writers. When they would talk shop, and it seemed like the issue of ownership came up every time. This was in the mid-eighties, before the black and white boom. With few exceptions, creators at that time had to make the hard decision of making a living in comics or owning and controlling their work. After hearing this complaint enough times, Richardson decided to do something about it.

In the summer of 1985, he brought together some of his creator friends and announced he wanted to start publishing comics with them. Just like when he opened Pegasus, they were skeptical. A comic company based in Oregon? Unheard of. But when he offered them 100% of the profits from the first issue, they were a little more willing to take a chance.

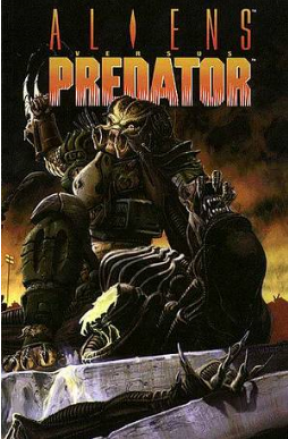

“Dark Horse Presents” was published in July 1986. Everyone involved had hoped the anthology would sell 10,000 copies, but they ended up with orders closer to 50,000. It was followed later that year by “Boris the Bear”, which was another success. Nine additional creator-owned titles were added to the line up in 1987. By Dark Horse’s second year of operation, it had already surpassed it’s 5-year goal of 5% market share. Going forward, Richardson decided to try something different. He obtained licenses to the Alien and Predator films in 1988 and turned them both into hits. Those helped him secure the Star Wars license in 1990, bring even more attention to his little publishing house.

It was about this time Richardson was talking to artist Geof Darrow, who casually mentioned a book he was working on with Frank Miller. Richardson asked if Dark Horse could have a chance at the book, which led to a meeting at a restaurant between Richardson, Randy Stradley (a Dark Horse employee), and Miller a few months later. Richardson handed Miller a few pages that itemized all the costs of printing a comic book, then asked Miller to decide what percentage of the profits Dark Horse could have. The meeting lasted about 15 minutes, ending with Miller saying he’d meet them again the next day. That night, Miller called Dave Gibbons, an artist he was collaborating with on an unrelated project, and told him about the meeting. When the three met again the next day, Miller agreed to let Dark Horse print his book with Darrow (“Hard Boiled”) and offered them first shot at his book with Gibbons (“Give Me Liberty”) on the condition Dark Horse take a more fair (read: larger) portion of the profits.

Having been in the publishing business for seven years, Richardson decided 1993 was the right time to try making superhero comics. The fictional universe they created for the Dark Horse heroes to share was known as “Comics’ Greatest World”. It was literally built from the ground up; before creating any characters, the team responsible for the line crafted four cities where the stories would take place. Once the environments were established, they considered what kind of heroes and villains would populate these places. They ended up with four concepts for each city, a total of sixteen books. CGW was introduced to readers through a 16 for 16 deal: Dark Horse published sixteen books, sixteen pages each, for $1 a piece. Ongoing series were launched after this affordable beginning, and the line lasted until 1996.

Continued belowAround the same time, Image was making a splash. Superstar creators were announcing new books that would rocket to the top of the sales charts, then fail to deliver the product in a timely manner, if at all. Frank Miller and some of his friends like the ideas behind Image, but felt the younger creators were letting their own hype go to their heads. They decided to take the Image ideals and do it the right way – assemble great, reliable talent and deliver great, reliable creator-owned comic books. When they needed a publisher to back them, Dark Horse was the logical choice.

To distinguish themselves from Image, which was all about appearances, they wanted a name that would reflect their focus on stories. They decided on Legend, a name suggested independently by both Miller and John Bryne. The original members were Miller, Byrne, Art Adams, Mike Mignola, Geof Darrows, and Dave Gibbons. Other creators would join later, including Michael Allred and Walt Simonson. A couple preexisting books, like “Hard Boiled”, were brought under the Legend umbrella, but most of the group used the opportunity to start new stories from scratch, such as Mignola’s “Hellboy”.

Unfortunately, Legend had a rough start. The group formed in 1994, which was a bad time for the industry overall. Making matters worse, retailers and readers didn’t seem to get the point of the imprint. Many of them assumed the books were supposed to exist in the same universe, when in reality the creators were doing their best to tell people that none of the stories were connected. The message didn’t spread far enough or fast enough, and a group of retailers actually voted Legend “Worst New Universe” six months after it began because of the lack of cohesion between books. To make matters worse, some of the members fell victim to the same troubles that Legend had been formed to oppose – delays and hype for books not yet available. The imprint was eventually discontinued in 1998, with some of the titles that originated from it continuing under Dark Horse proper.

Meanwhile, Dark Horse was dealing with a behind-the-scenes burden. Because of some bad decisions by Marvel, the network of distributors that moved comics from publishers to retailers was capsizing. Faced with the very real possibility that a competitor could purchase one or both of the national distributors and leave Dark Horse with no way to get their books to readers, the company signed an exclusive distribution deal with Diamond Distribution in the summer of 1996. Diamond, the largest North American comics distributor, had already made a similar deal with DC and was in the process of inking one with Image. This was the smart decision for Dark Horse, but it spelled disaster for Diamond’s chief competitor Capital City. Capital had once been comic’s second largest distributor, but the sudden loss of goods from the industry’s largest publishers caused it to hemorrhage revenue. Less than six months after the Dark Horse deal, Diamond purchased the failing Capital City.

Depending on how it’s defined, Dark Horse had probably stopped being a small press company long before 1996. It had produced work by top creators. It had top selling books. It had films based on its properties. It had a large enough market share to be listed by itself, instead of being lumped into the “other” category in comics catalogs since at least 1992. But when Dark Horse signed its deal with Diamond, it became one of the three (soon four, when Marvel joined) premiere publishers. Obtaining this special status is a defining moment for the publisher, and it’s where the line is being drawn on Dark Horse’s small press years for this article.

Looking back at Dark Horse’s rise from a crazy idea to a major force, you may wonder if it’s a strategy that could be duplicated by a different company today. There were a few significant factors at play here, but none of them were necessarily exclusive to Dark Horse or Mike Richardson. First, Richardson had already demonstrated his business acumen by turning one new comic shop into several. Rare, maybe, but still common enough. Second, he had contacts in the industry. These require time, but are readily available to someone who puts the effort toward it. Third, he was willing to give creators a fair deal when others weren’t. Remember that pricing sheet Richardson gave Miller? The reason it made such an impression on Miller is because he’d never seen one before – other publishers had always hidden that side of the process and only told him how much his check would be. Today, creators are treated much better, so it would take even more effort to really impress them. Fourth, he tried new things. Not costume-change new, but new-new. That’s still possible today, but it would also require more innovation. Between Dark Horse, IDW, and Image, there’s a lot more variety than there was in 1986.

So, could the Dark Horse method be someone else’s path to success? Certainly, if they’re willing to work as hard as Mike Richardson did.