Multiversity’s history column returns with a look at the comic industry from 1951.

Current events

America saw its share of turbulence in 1951. The Korean War had just begun in November 1950, and the public was still trying to get over World War II, which had ended just five years earlier. This new conflict was geographically smaller, but the stakes seemed much bigger now that allies of both sides had nuclear weapons. Closer to home, everyone was aware of a rise in youth crime. A 1952 government report found that annual juvenile delinquency rose 10% nationally in 1951, and 20% in New York City specifically. That broad of a change in such a short time led parents to conclude their kids’ problems couldn’t be their fault, so everyone was looking for a scapegoat. Media outlets, which were just as sensationalist 70 years ago as they are today, downplayed the fact that 1950 was a 14-year low in juvenile delinquency and that a 10% jump in 1951 still put the nation below average. They also downplayed the analysts who said the Korean War was the most likely cause of the increase – the absence of brothers, fathers, and sons was needed to fight those godless commies, and reporting a downside to it would be quite un-American.

An obvious and easy target for the blame was the comic industry. It had been regularly attacked for over a decade at this point and was still seen as a dangerous new medium. Who really knew what looking at four color panels could do a kid’s eyes or brain development? It might be fine, but do you want to take that chance with your kids? It didn’t help that so many comics had been focused on crime and criminals for the past few years, nor that there was no union or industrial coalition to defend the material. In March 1951, the Senate Joint Legislative Committee to Study the Publication of Comics found that comics stimulated abnormal sexual tendencies in teenagers. (At the time, that probably meant any tendencies at all. Free love was still a decade away.) However, it did not propose any legislation to regulate comics or their content. The report didn’t say why, but it probably had something to do with the First Amendment dooming any such regulation. Well-meaning psychologist and comic boogie-man Frederic Wertham encouraged Senator Estes Kefauver to pursue comics further, but that movement was still a couple years off.

Comics Content

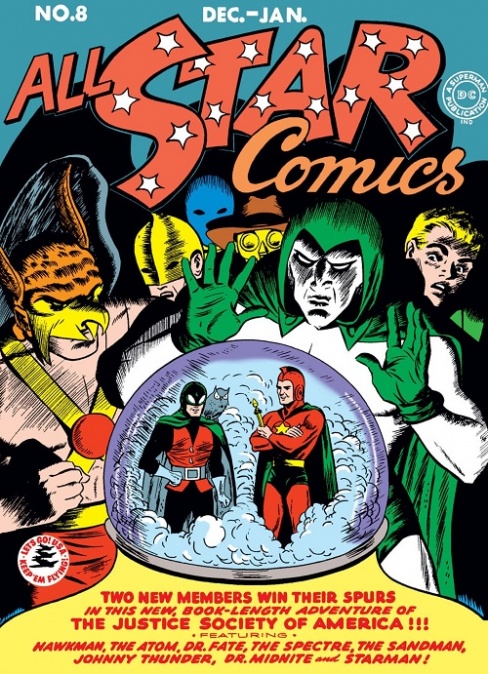

Superheroes hit a nadir in 1951. In the Spring, DC changed the name of “All Star Comics” (home of the Justice Society) to “All Star Western” (home of westerns) effective at issue #58. For most historians, this officially marks the end of the Golden Age of Superheroes that began with the debut of Superman in 1938, but the genre had been waning for years. It wasn’t just superheroes in comics, either – the Superman radio serial ended in 1951 as well. Superheroes didn’t die out completely, of course. Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman all remained strong enough sellers for their titles to survive. DC tried moving “Action Comics” to 52 pages for a short time, but the experiment didn’t make it through the year and it was soon down to 44 pages (including the cover).

Crime and romance comics were also on the way out. Crime was suffering from the bad press it had been getting since its debut in 1942. Romance sales were lagging, so publishers tried to give it a boost by crossing it with the up-and-coming western genre, begetting titles like “Cowboy Love” and “Cowgirl Romances”. This specific sub-genre was chugging along in 1951, but was was slowly evolving into pure westerns. Both crime and romance took a big hit when publisher Victor Fox decided to close up shop. His so-called headlight comics had been a target for criticism for a long time and sales for his books specifically were hurting long before the Senate witch hunts coming up in 1953. Fox had been a big believer in flooding the market when he saw a trend, and he’d been heavily invested in crime and romance in 1951. While the number of genre fans might have been steady at the time, the loss of Fox meant the number of titles and overall circulation dropped drastically.

Continued belowNot all genres had a bleak outlook, however. As mentioned, Western was on the way up. So were horror and science fiction in the EC tradition. Both of these genres were ripe for popularity thanks to the genuine fear of nuclear Armageddon and other scary scientific advances. Horror comics gave readers an outlet for their existential angst, and science fiction stories often displayed the beneficial side of new technologies.

Meanwhile, Gilberton decided to set their “Classics Illustrated” series apart from other comic publishers by issuing reprints of older classic-literature adaptations with new painted cover art that made them look more like real literature. Interiors remained unchanged, but were now printed on heavier paper stock and the price went up to $0.35, an outrageously high amount that virtually guaranteed all copies sold were to parents, not kids.

Other minor events

Comic book founding father Will Eisner and his American Visuals company had been working for the government producing the US Army’s monthly “Preventative Maintenance” magazine since World War II. Among other things in the magazine, readers found tips and instructions for keeping their equipment in good working order presented in comic format. When showing a GI how to change oil in a jeep, for example, Eisner would be able to show POV shots in a way that was far more helpful than a basic diagram. His experience with storytelling also aided him in walking through the process. The material was often surrounded by puns and double entendres to keep a soldier’s attention.

In 1951, with the advent of the Korean War, the Army revised their program. “Preventative Maintenance” was canceled and replaced by “P+S, the Preventative Maintenance Monthly”. Eisner and American Visuals continued to make it and retained some of the recurring characters from the previous monthly’s strips: Joe Dope and Connie Rodd.

The Korean War had still another impact on the comic industry: the positive economic benefits from it prompted Canada to lift some of the protective import restrictions it had put in place in 1948. This included comic books and had allowed a Canadian comic industry to briefly flower. In 1951, the restrictions were lifted, American comic books flooded Canadian newsstands with superior quality and a good value. Unable to compete, the Canadian publishers were soon out of business.

Finally, there was one more minor event from May 1951. Lev Gleason stepped down as the head of the ACMP, an organization he helped form in 1947. He was replaced by Harold Moore. Nothing of consequence came from this leadership change, but that’s the way it was.

Like this? Check out the archive by clicking below.