I’m taking a slightly different approach to today’s column. Instead of looking at various events from several different years, I’m going to focus on events from a single year: 1970.

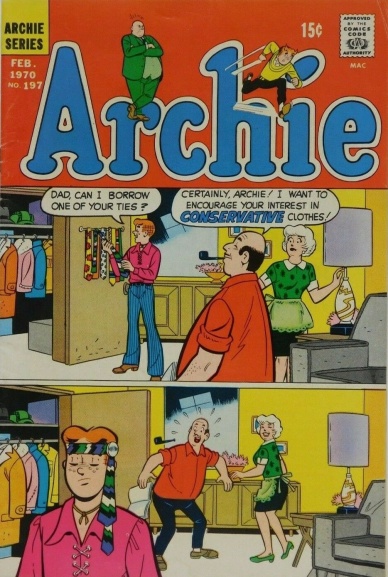

By 1970, DC and Marvel were the undisputed top publishers in the comic industry, and the gap between them and third place was wide enough and stable enough for a phrase like “the Big Two” to make sense to comic fans. In the face of this apparent security, pay rates for creators could still be frustratingly low. Denny O’Neill was one of DC’s highest paid writers, but he still had to take on side jobs to survive. Interestingly, in spite of the overall superhero dominance of the market place, the title for top-selling comic belonged to “Archie”.

The winds of change were beginning to blow in 1970, although the significance of certain trends wouldn’t be apparent for many years to come. For example, a group of New York University students made a film called We Love You, Herb Trimpe featuring commentary from some of the artist’s coworkers at Marvel, and more than one of them had misgivings about their aging audience. The average reader would continue to be 8-15 years old for a few more decades, but the buying power of the older minority would make itself felt much sooner.

Part of that influence came through a growing number of comic specialty shops. The first couple had opened on the West coast in 1968, and the popularity of conventions prompted new ones to continue opening across the country through 1970. Their focus was almost exclusively back issues by necessity – although they knew there was demand for new comics, the store owners had no easy way to order what they wanted. Phil Seuling, the 36 year old teacher who ran the New York Comic Convention, was working on a solution, but it was still a few years away.

In a development related to the growing number of conventions and specialty stores, Bob Overstreet published the first edition of his price guide in 1970. Gleaning his information from prices listed in adzines and mail order catalogs, Overstreet manually organized his data in a format similar to a price guide for coins called the “Red Book”. The first printing was 1,000 copies and sold for $5 each. It stood out from other industry guides by being the first to include ads, but its lasting impact came from setting a common grading system using nomenclature borrowed from coin collectors.

In addition to Richard B Nye’s attempt at chronicling comic history in an academic fashion discussed in last month’s coverage of “

The Unembarrassed Muse“, two other notable efforts were made in 1970. The first, “All in Color for a Dime”, was a collector-oriented collection of essays about comic books from future “Comic Buyer’s Guide” editor Don Thompson. The second was “The Sterenko History of Comics”, the first of six planned volumes by “Nick Fury” writer/artist Jim Sterenko. It was often exaggerated or inaccurate, but it was the first honest attempt at a history of comic books. The second volume was released in 1972, and the remaining four are still forthcoming.

On the creator side, Jack Kirby’s frustration with Marvel reached a breaking point. Angry about the lack of credit and compensation he was receiving, he worked out a deal with DC that guaranteed him better pay. Kirby probably felt the switch was a long time coming, but Stan Lee certainly seemed to be caught off guard. Kirby was living in California at the time, but someone in Marvel’s New York office pinned a cigar to a bulletin board with a note reading “I Quit”.

In an unusual move for the time, DC actively promoted Kirby’s arrival with in-house ads and teasers like the one above. When Kirby’s DC output was finally released, the sales were lukewarm at best and future scholars would sometimes use this as evidence that Kirby had need Stan Lee to write more than he’d believed.

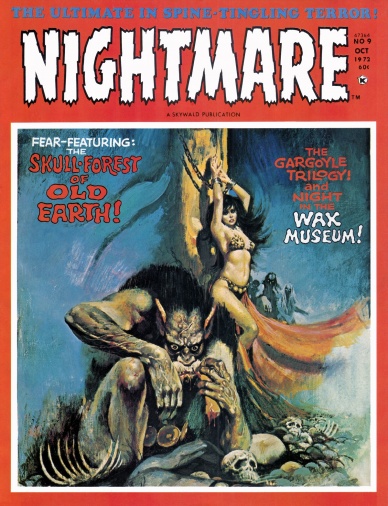

Another event from 1970 worth discussing is the brief existence of the publisher Skywald. Israel Waldman had come into ownership of some classic comic characters and wanted to provide the financial backing for a new company. To get it off the ground, he went to Sol Brodsky, a long-time Marvel employee who knew just about everything there was to know about production. Ever the company man, Brodsky even asked Stan Lee if he’d mind him leaving to start a rival company. With Lee’s support, Brodsky left to form Skywald.

Continued below

Skywald’s main output was black and white comic magazines. They mostly fell into mystery, horror, and fantasy genres with creators like Mike Esposito and Ross Andru. Distribution problems wasted a lot of capital as large print runs sat in warehouses. Waldman chose to cut bait and pulled his funding, leading to Skywald’s collapse. Brodsky returned to Marvel, but his production manager position had been filled by John Verpoorten. Instead, Brodsky found himself running Marvel’s British department.

The final item in today’s retrospective of 1970 comes courtesy of that scoundrel, Frederic Wertham. Twenty-five years after he began stirring up an anti-comics crusade and sixteen years after his actions neutered the industry with the Comics Code, the shady psychologist wrote a letter to the comic book fanzine “All Dynamic”, claiming that his critics had turned him into a straw man and misrepresented his arguments. He had never advocated for a censorship body like the CCA – he merely thought violent comics caused children to give in to violent impulses. How he made a distinction between a censorship body and getting publishers to stop printing popular content, I’ll never understand.