Comics have been around for a long time and there is no shortage of fascinating stories in the history of the medium. This column looks back at select events that occurred during the calendar month from years long gone. Here are a few from Marches past.

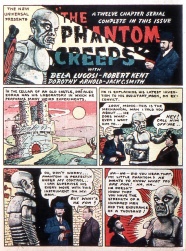

In 1939, when comic books as we know them were about six years old, the All-American Comics imprint of National Allied Publications (DC) was the first to try adapting films into comics. “Movie Comics” #1 was the effort of editors Max Gaines, C. Elbert, and Sheldon Mayer. It was released with an April cover date with the intent, according to its table of contents, to “serve as a permanent record of the pictures [the reader has] enjoyed”. Television was invented about the same time this issue was released, and the idea of home video was still science fiction.

The first issue was 64 pages, but the page count increased to 68 pages in later installments. The stories inside were mostly eight pages and included contemporary hits like Son of Frankenstein, Gunga Den, The Great Man Votes, Fisherman’s Warf, and Scouts to the Rescue. Each one was illustrated with still frames take from the films that were retouched with airbrush and inks. The results were in the bad region of the uncanny valley and the title was canceled after six monthly issues.

Rival publisher Fiction House revived the title and concept with traditional art in 1946, but it was met with the same lack of success and vanished after only four issues. Dell and Gold Key tried again in the 1950s and finally found an audience. The original still holds some interest for readers, and it was the inspiration for Blair Davis’ 2016 book “Movie Comics: Page to Screen/Screen to Page”.

The early 1950s was a tense time in America. There was a perceived increase in crime among the youth, despite actual arrests leveling off at the start of the decade. Parents everywhere wanted to blame their child’s juvenile delinquency on something from outside the home, throwing accusations at everything from Communism to television to comics. Feeling the populist sentiment, a Democratic senator from Tennessee with presidential ambition promised to uncover the real cause(s) and fix the problem

The Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency first convened in August 1953, and it finally got around to hearing testimony about and from the comic industry on April 21 and 22, a Wednesday and Thursday. Although the committee was chaired by Robert Hendrickson, Senator Estes Kefauver took the lead in targeting comic books. In his opening statement, Hendrickson made plain that they were only interested in hearing about comic books, not comic strips, and more specifically about horror and crime comics. He acknowledged this was “only a fraction” of the industry. He also claimed no one on the committee had preconceived ideas about possible regulation for the industry. Over the two days of testimony, the committee heard from 28 witnesses, including child psychologists, social workers, comic book publishers, and cartoonists.

Most of the testimony was bland, but you can read it yourself here. The first witness was the also the committee’s staff director, Richard Clendenen, who testified that he found no evidence of a conspiracy among publishers with the intent to corrupt youth, just that they published comics that would sell. Herbert Wilson Beaser, the associate chief council, used this opportunity to declare that this meant publishers were amoral men who were only interested in money.

Dr Frederic Wertham was the fourth witness, and he opened with a 20-25 minute statement of his qualifications. He went on to criticize comic books of all types, at one point even implying they were singularly responsible for 26 girls getting pregnant in an unnamed New York state high school. To their credit, some of the senators seemed skeptical of his alarmist claims when they asked if there were factors worth considering outside of comics. They also pointed to a Canadian ban on crime comics which had failed to reduced crime in their country. Not Kefauver though. He compared the apparent instructions for crimes in comics to Hitler’s method of repeating lies until people believed them, prompting Wertham to call Hitler a beginner relative to comic publishers. Keep in mind that this was 1954, less than a decade after World War II had ended.

Continued belowWertham was followed by EC publisher Bill Gaines, who falsely told the committee he was responsible for starting horror comics. Gaines was there voluntarily, and he naively thought he could tell the senators his side of the story and make the whole mess go away. Instead, he introduced himself to the committee with a satirical ad calling them communists. Then he unintentionally made the oxymoronic claim that crime comics are incapable of inducing a child to violence, but that wholesome comics can induce a child to live a better life. By the time he realized he was out matched in the rhetorical arts, it was too late. He ended up looking like a fool unaware of the power his publications had, and made the rest of the industry look bad with him.

The next two witness appeared together. Walt Kelly and Milton Caniff represented the Cartoonists Society. They opposed any new legislation, and Caniff made an eloquent statement about tarring all crime comics with one brush. Instead, he said he prefers to judge them individually as good or bad based on how they affect him personally.

Later witnesses, like attorney/publisher William K Friedman and psychiatrist Dr Lauretta Bender reiterated that despite the millions of comics in circulation and the volume of juvenile arrests, there was not one case in evidence where a comic could be shown as the direct cause of a crime.

In the end, the committee had no recommendation for legislation or regulation of comic books, but they endorsed the creation of the Comics Code Authority. Kefauver ran for president in 1956 but ended up on the ticket as the Adlai Stevenson’s vice president. They lost to Eisenhower.

When Wall Street mogul Ron Perelman bought Marvel Comics in 1988, he set out to make a quick buck off of it. The pursuit of profit led to many things, including a massive amount of new comic titles, gimmick covers with increased cover prices, and licensing of virtually every type. One thing it did not include was films. Films take a long time to produce – too long for Perelman.

Some members of the Marvel staff thought movies were the best way for the company to move forward, namely Ike Perlmutter and Avi Arad. Arad became the head of Marvel Films in 1993, a division that had been around since 1980 but never been very successful. The success of the X-Men animated series gave him the clout to push through a deal with Fox to make a live action X-Men film, but it took about 7 years longer than expected to deliver.

During those 7 years, Perelman’s business decisions earned him a small fortune but put Marvel in bankruptcy. The final outcome saw Perelman replaced by Perlmutter, largely due to the latter’s ability to convince investors that films could turn the Marvel around. The bankruptcy was finalized in December 1998, and X-Men followed in the summer of 2000. Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man came out a year later. Both made large sums, but Marvel didn’t see much of the money because of the deals they had to cut with the studios to get out of bankruptcy. They got a flat fee for X-Men instead of a percentage.

The idea for a cinematic universe similar to the Marvel universe, where characters from one franchise regularly interact with others, was first proposed by talent agent David Maisel in 2003. It took two years of preparation and planning, but on April 28, 2005, Arad and Maisel (now Chief Creative Officer of Marvel Studios, renamed from Marvel Productions in 1996) held a conference call to announce they had made a deal with Merrill Lynch to create their own films. Merrill Lynch provided $525 million to finance 10 films over eight years, with Marvel using the film rights to Ant-Man, Black Panther, Captain America, Doctor Strange, Hawkeye, Nick Fury, Power Pack, and Shang-Chi as collateral. Three years later, Iron Man debuted in theaters and inaugurated the Marvel Cinematic Universe.