In 2020, this column is trying something new. I normally examine three events from comic history that are connected to the month the column appears, and I’ll still be doing that the first Monday of every month. Unfortunately, not every event in comic history can be pinned down to a particular month, and that means I’ve had to skip some interesting topics. Until now, that is…

Going forward, this column will be put out twice a month. The first edition will be the Ghosts you’ve all come to love. The second edition, scheduled for the third Monday of a month, will look back at events that occurred in 2010, 2000, 1990, or some other year that ends with a zero. If I can maintain this for another twelve months, it’ll roll over to 2011, 2001, and so on in that fashion until we’re ringing in 2030 and I ask myself if I can get away with re-running this column instead of writing a new one.

So, without further ado:

The academic definitions of “comics” are often broad enough to include things that aren’t considered comics by the average person, including the Bayeux Tapestry shown above. This is just a segment of it, because the full piece is 230 feet long (70 meters). The artwork is delineated into clear segments, each one showing an event after the previous one. All together, this tapestry tells the story of the Norman conquest of England that began in 1066.

I won’t argue with anyone who feels the sequential artwork makes this a comic, but that kind of claim has always struck me as a feeble attempt to give the modern industry some undue gravitas by association with something more respected.

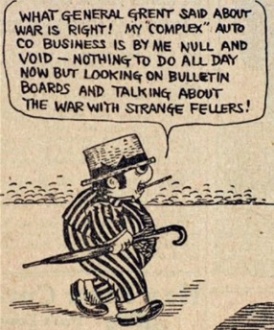

Comic strips were booming in the 1900s, and cartoonist Harry Hershfield has the dubious distinction of being the first cartoonist to use ethnic humor when he created “Abie the Agent” in 1910. I haven’t read any of them personally, but in 1970 Russel Nye described the script about a Jewish husband and wife as “done with wit and good humor”. It was the first strip about family life to separate itself from the pack and served as the basis for the genre over the next couple decades.

In 1910, aspiring cartoonist George Herriman drew a strip where a mouse threw a rock at a cat. After a year of development, he launched “Krazy Kat” on a 35-year journey of hi-jinks. Krazy Kat and Ignatz the Mouse laid the foundation for Tom and Jerry, Tweety and Sylvester, Wile E Coyote and the Roadrunner, and Itchy and Scratchy. Like the Aristocrats, these all use the same basic joke with the fun being in the setup instead of the punchline.

1940

The modern comic industry was off to a roaring start in 1940, and the industry was still trying to work out some internal standards. For example, no one seemed quite sure how much an artist should be paid. Lloyd Jacquet, a founder of what became Archie Comics and head of the packaging shop Funnies Inc, was able to secure some solid talent for $7 per page. At the same time, Martin Goodman, publisher at the company that became Marvel, was a tightwad but was comfortable paying $12 per page. Meanwhile, Will Eisner and Jerry Iger were shelling out salaries of $25 per week because they were after quality instead of quantity. As an artist himself, Eisner also wanted to provide the artists some security and avoid any resentment over corrections. (With a page rate, corrections were basically free labor.)

DC’s “Sandman” was only in its second year in 1990, but it was already receiving praise from some mainstream outlets and back issue prices were rising. When “Rolling Stone” was planning to give it some significant coverage, DC Marketer Bruce Bristow knew demand was going to explode and he wanted DC to reap benefits beyond an increase in monthly sales.

The bookshelf format – square-bound reprint collections – had been around for a few years, but DC was limiting it to special projects like “Watchmen”, “Ronin”, and “Dark Knight Returns”. You know – graphic novels that just happened to be serialized first. Bristow’s idea was to put out a reprint collection of the second arc of “Sandman” (the one “Rolling Stone” was covering). That way any new readers the article brought in could pay DC for it, not just back issue dealers, and there would be plenty to go around.

Continued belowThis is an obvious idea in retrospect, and probably felt pretty natural to Bristow at the time, too. There was no reason to omit ongoing series from DC’s reprint program. The success of the “Sandman” collection led to DC to produce more collections of popular story lines, although they did not follow the concept to its logical conclusion. That came about ten years later…

When Bill Jemas was brought on board to guide Marvel out of bankruptcy and into the new millennium, one of the first things he did was look for ways to expand the company’s distribution options. The most apparent untapped market was bookstores, and Jemas asked Barnes & Noble what would make comics appealing to them. Their advice? Collections of six regular sized issues were the ideal size.

Jemas passed that guideline on to writers. I can’t speak to how it was presented, as a gentile suggestion or a politely-worded command (it probably depended on the editor), but there was a very real incentive for creators: a six-issue story would get the collection into bookstores and generate additional royalties. Some writers adapted to it well, thriving when they could give a story room to breathe (see “Ultimate Spider-Man” vol 1). Other writers took the weak way out and turned a 1-issue concept into a 6-issue snorefest (see “Ultimate Spider-Man” vol 15).

Within a few years, readers everywhere were debating the merits of decompression. The debate was moot, however, because there was no going back. Tradewaiters became an important element in sales and publishers cater to them by offering mostly-complete story chunks without skipping anything in between. Now the real debate is whether there’s any tangible difference between a reprint collection and a graphic novel.

That question of definitions brings us full circle for this article. See you in February.