Multiversity’s history column is back with coverage of events themed around the month of March. The first three items are about Canada. The last is about American attitudes toward manga and comics. Enjoy!

March 1941

When modern comic books arrived on the scene in the 1930s, they were an immediate hit. New publishers seemed to spring up every month and it wasn’t long before the American market was overflowing with new books. Canadian businessmen wanted in on this action too, and economics made it more attractive to import the American product than to produce their own. That setup worked fine until Adolf wrecked things by starting World War II. Canada’s strong ties to Britain meant she entered the fight two years sooner than her cousin to the south, causing their economic interests to diverge.

In response, the Canadian Parliament passed the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA) in December 1940. Among other protectionary provisions, WECA banned the import of comic books. This created a sudden vacuum in the publishing field which many Canadians were ready to use to their advantage. It didn’t take long.

Maple Leaf Publishing was the quickest one out of the gate with “Better Comics” #1 in March 1941. This was the first comic book created entirely by Canadians (opposed to, say, a Canadian drawing an American’s script). It also saw the premier of the first Canadian superhero among its five features. He was the Iron Man, a strong man who lived in an underwater city. Almost all 48 pages of “Better Comics” were the product of one man: Vernon Miller. The exception was a script by Frederick Percy Thursby used for the one of the stories.

The first issue had a few pages of color, but it was mostly black and white. Later issues of “Better Comics” switched to all black and white interiors to reduce costs – a tactic used by other Canadian publishers as well. This uniform lack of color gave the books an identity and set them apart from their colorful American cousins. Years later, fans would label them “Canadian Whites.”

WECA was repealed in stages after WWII ended. By the end of 1946, all restrictions had been lifted. Cheaper American comics returned, but the wartime restrictions had allowed the Canadian comic industry to build to a critical mass that gave the homegrown publishers the resources and the motivation to try competing instead of giving up. As it turned out, there was help on the way very soon…

March 1948

In the post-war era, there was a global economic boom. In 1947, Canada found itself facing a massive trade deficit with the US and UK. Parliament responded swiftly by passing a new protectionary act on November 17. The gap between WECA and the Foreign Exchange Conservation Act (FECA) is so short that even contemporary economists treated them as a continuous policy. For the specialized focus of comic fans, however, there are important distinctions.

Under WECA, it wasn’t just comic imports that were banned – not even engraved printing plates could get through customs. FECA wasn’t quite so strict, which allowed Dell to skirt the law by allying itself with Wilson Publishing Co in Toronto. Starting in March 1948, Wilson used Dell’s printing plates to produce Canadian editions of Dell comics that varied significantly from the American versions. The most obvious change was the page count, which was reduced to 36 from the American 52 (counting the covers). Because the printing plates weren’t available until the American print run was complete, the Canadian version of a given story was released 6-8 weeks later. This occasionally caused a problem when Dell used a seasonal cover, as Wilson didn’t want to release Halloween material in December, nor Christmas material for Valentine’s Day. This was solved by simply switching covers. Presumably, any seasonal interiors were in the cut 16 pages, or replaced by material left out of earlier editions.

EC came to a similar arrangement with Canadian-based Superior Comics (formerly Dynamic) in 1949, but with different results. Instead of reusing the original printing plates, Superior received duplicate plates made from asbestos. The resultant comics were significantly lower quality. There was also an occasional error, like putting the interiors for “Frontline Combat” #12 behind the cover for “Frontline Combat” #11 and vice versa. Maybe there were practical explanations for this (I can think of several good ones), but none was ever disclosed to my knowledge.

Continued belowThe Bell Features group was another Toronto-based company that licensed select comics from Marvel, Archie, and Quality.

March 1951

Just as a foreign war triggered Canada’s protectionism, it was another foreign war that ended the policy. Canada’s economy had rebuilt itself and the trade imbalance was greatly reduced by 1950, when North Korea surprised the world by invading South Korea. The economy got a boost as the government began buying war supplies, and FECA expired. Although Canadian publishers lobbied to resist the loosening of import restrictions, they failed.

Pretty much the moment FECA ended, Dell ended its partnership with Wilson – the last Canadian edition of Dell product was released with a March 1951 cover date. Bell Features faded away as its licenses expired. Superior held on for another few years by producing original horror and war content that was exported to the US, but was one of many publishers to walk away when the Comics Code Authority crippled their content.

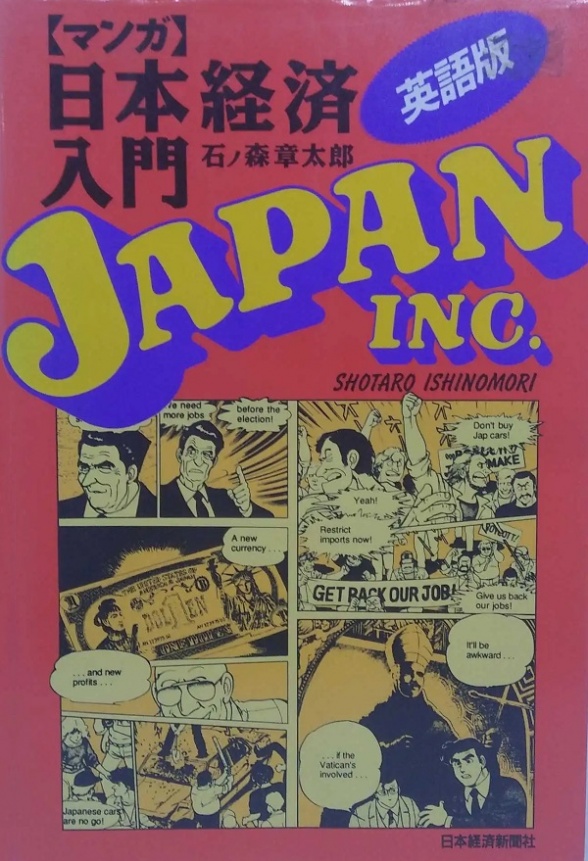

In late 1988, Shōtarō Ishinomori wrote “Japan Inc: An Introduction to Japanese Economics.” It was translated to English by Betsey Scheiner and published in America by the University of California Press. The book was 300+ pages of detailed work meant to be a primer for serious students of the topic. It was also completely presented in manga.

The March 15, 1989 issue of “Library Journal,” a trade publication that helps librarians stay on top of their craft, included a review of “Japan Inc.” Unlike every other review from “Library Journal,” however, it never discussed the book’s quality or merit. It made no recommendation about what kind of library would benefit (or not) from its inclusion in their stacks. Instead, it focused entirely on the manga format. “[O]ne could assume it is a scholarly work,” we’re told, “but, golly gee, Batman, it’s a comic book!” It goes on to inform readers that the Japanese don’t see anything unusual about serious nonfiction in comic form, using a condescending tone that suggests we Americans know comics are really just meant for kid stuff.