Welcome back to Multiversity’s history column. This week, I’m going to tell you about some exciting events from October 1940, October 1970, and October 1993. You’ll be thrilled by the first Disney comic! You’ll be chilled by the debut of “Conan” and the lies told about it! You’ll laugh and cry at the rise and fall of Legend comics! But enough overstated introduction – let’s get to it!

When most people watched Disney’s cartoons in the late 1930s, they saw entertainment. When Helen Meyer watched them, she saw opportunity. As a Vice President at Dell Publishing, she reached out to the Walt Disney Corporation to negotiate a license to create comic books based on the popular characters. The agreement had Dell distribute Disney Comics that were published by Western Printing & Lithography.

KK Publishing had been putting out “Mickey Mouse Magazine” since the Summer of 1935, which included some reprints of Disney comic strips among its games and prose, but no new comic material. As part of Meyer’s deal, that magazine was converted into Dell’s “Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories”, which was all comic content. The first issue debuted October 1940 with more reprints of comic strips.

This wasn’t Dell’s first foray into the comic book business – they’d been pioneering the format since 1929 with just enough success to continue. “Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories” changed that, becoming the company’s first major hit with sales around 2M copies per issue. This was the first “funny animal” comic book, and Dell tried to corner the market over the next couple years by licensing Warner Bros’ “Looney Tunes” along with other forgotten characters by other forgotten studios. In December 1941, they debuted “Animal Comics” starring Walt Kelly’s Pogo.

The title of the anthology was part of a charade to convince the public that Walt Disney was creating all this material himself, which is why none of the material was credited. In April 1942, Donald Duck became the lead feature and original stories began with “Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold”, which was based on an unmade film. Changes in creators was obvious to readers, and many of them could tell when a story was made by the “good duck artist”, even if they didn’t know his name. An investigative fan identified him as Carl Barks in 1960, but the scoop was suppressed in the fan press at Disney’s request until after Walt Disney’s death in 1968.

Through the 1950s, sales of “Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories” fell from their once-great highs of 3 million copies per issue. In 1960, despite still being the best-selling comics in America, “Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories” and its spin-off “Uncle Scrooge” sold over 1 million comics for the last time. (That sales barrier wasn’t broken again until “Star Wars” #1 was released in 1977.) In 1961, Dell’s overconfidence in the popularity of its content led them to raise cover prices from ten cents to fifteen. Other publishers held out at the ten cent price longer, then moved to only twelve cents. Pennies made the difference, and by 1962 sales of “Comics & Stories” were under 500,000.

The name recognition of the title kept it alive long after Dell left the comic business in 1973. “Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories” has been canceled and revived many times by many publishers, including its most recent return at IDW in 2015.

By the end of the sixties, the Marvel Age was fading and comic readers were losing interest in super heroes. Some creators, like Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams on “Green Lantern”, tried to revive the genre with a new level of realism. That darker, grittier approach was a bit ahead of its time, and its critical acclaim didn’t boost sales.

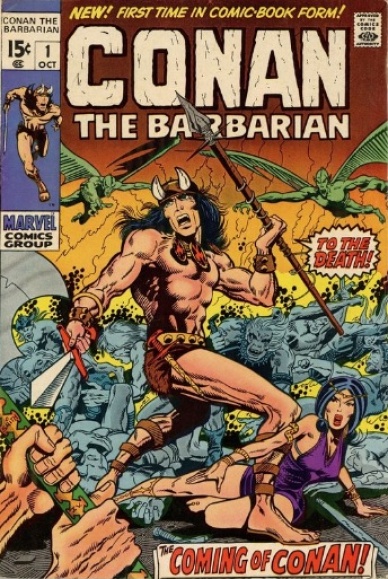

Other creators, like Roy Thomas and Barry Smith, decided to try something completely different. As fans of Robert E Howard, they pushed Marvel to buy the license for “Conan” for $200, even though that far exceeded the budget laid down by their publisher Martin Goodman. The first issue was released in October 1970, and it became an instant hit that drew in a whole new audience.

Continued belowThe third issue adapted a popular Conan story and was in higher demand than the second issue. This presented a challenge to the early back issue dealers whose clientele had immature conceptions about what made comics collectible and valuable. Thanks to news coverage of high ticket sales of books like “Action Comics” #1, everyone knew that first issues were valuable – they were first and they were old. But how do you explain that you’re charging more for #3 than for #2 when the supply/demand argument will come across as the exploitative “I’m charging you more because you want it more, and I can.”?

Simple. You lie.

First issues are worth more than second issues. Everyone knows that. What else does everyone know? That rare things are worth more than common things. So, why does “Conan” #3 cost more than #2? Because a distribution problem resulted in fewer copies of #3 coming to market. This lie was organized and consistent for a long time, which is why the Overstreet Price Guide still has a note indicating the issue had “low distribution in some areas”. As the back issue market matured, the concept of a “key” issue took root and this kind of lie was no longer needed.

“Conan” continued to be a hit throughout the decade and was one of Marvel’s top three sellers. It endured through the superhero revival of the 1980s before finally succumbing during the market downturn in the mid 1990s. Its final issue, #275, was cover dated December 1993.

The formation of Image Comics was a massive disruption in the comic industry. Among the many other types of responses to it, some established creators thought the young Image guys were making some rookie mistakes because of their inexperience. A few of those creators decided to show Image how it should be done.

An effort to start a creator-owned imprint began in Spring 1991 under the name “Dinosaur”. It was a loose group without much forward momentum or a coherent purpose. Two years and several name changes later, John Byrne and Frank Miller emerged as the leaders of Legend. Byrne’s public condemnation of many of Image’s practices and Miller’s public endorsement of their ideals led them to agree that Legend needed to happen. Dave Gibbons and Geof Darrow were brought in as friends of Miller, and Dark Horse recommended Mike Mignola, and Art Adams as potential members. The group sought Paul Chadwick as the final founder because his reputation was built on creator-owned work exclusively. Walt Simonson had been a member of the Dinosaur group, but he signed with Malibu’s similarly creator-owned Bravura imprint when Legend was forming. Chris Claremont was in talks to join, but Frank Miller vetoed his membership on the grounds that Legend was limited to cartoonists only – no writers or artists. Dark Horse officially announced Legend during a panel at SDCC 1993 to fanfare and excitement, followed by a cover story in “Wizard” #31.

Unfortunately, Legend had a rough start. The name was instantly trouble, because many observers mistook it as a self-description of the creators instead of their works. Byrne’s reputation for having an ego didn’t help. Their logo, an Easter Island head drawn by Mignola, was briefly mocked in print by Erik Larson’s Highbrow Entertainment, who felt the name was supremely arrogant.

Then there was confusion about what Legend actually was. The creators saw it as a unifying label they could apply to their creator-owned work from any publisher to provide some continuity to readers. In practice, all of the Legend creators were working with Dark Horse, so it gave a strong impression of being a Dark Horse imprint. This was exacerbated as time went by and it remained a Dark Horse exclusive.

Finally, there was confusion about what Legend wanted to be. It was supposed to be like Vertigo, where titles stood independent of one another, but this was muddled from the start when some (not all) creators did crossovers with other Legend properties. The summer of 1993 was the summer of the glut, the time when every publisher in North America was pushing a new superhero universe. Six months after their debut, a group of retailers voted Legend the “worst new universe”, which confirmed to the Legend creators that their message hadn’t been properly received.

Continued belowThe first comic to feature the Legend logo was “John Byrne’s Next Men” #19 in October 1993. It was soon added to existing books like “Sin City” and new titles like “Hellboy”. All of its titles received critical acclaim, although this didn’t always translate to great sales. Byrne’s “Danger Unlimited” miniseries was promoted as a top pick by “Wizard”, but orders were too low to justify an ongoing or second miniseries. Mike Allred joined Legend and Dark Horse in April 1994, bringing his “Madman” series with him from Tundra.

Legend had become a key element of Dark Horse’s lineup by 1995, but some members were failing to live up to the group’s ideals. Unpublished characters were being promoted in card sets. Creators were missing shipping deadlines. Legend was making the some of the same mistakes its founders had criticized in Image. Over time, the successful Legend books proved themselves independent of the imprint, the unsuccessful ones were forgotten, and the imprint itself became unimportant. When it stopped appearing on covers in 1998, there was no announcement or commentary. It was just gone.

“Hellboy” stands out as the most significant contribution from the imprint. Many of the other successful works were already established (“Next Men”, “Sin City”) or would have been popular anyway (anything by Miller and Gibbons or Darrow). Mignola, however, did not have the star power of his Legend peers. He freely admits that joining Legend was the best creative or business decision he ever made, and acknowledges the title wouldn’t have received nearly as much attention if it had just been another Dark Horse book.