Multiversity’s history column marks the release of Shazam: Fury of the Gods with a two-part overview of the character’s history. Today, we focus on the character before he came to DC Comics in the 1970s. Next week will cover the DC era. Our journey starts in 1939 and ends three months in the future, covering everything in between.

Please note “DC” will be used to describe the company that became DC regardless of its contemporary identity. Keeping track of their name changes is beyond the scope of this article.

In 1939, comic books were experiencing a major boom and publishers were scrambling to find the next Superman. Minnesota-based Fawcett Publications was a 20 year old magazine company doing well with its humor and family oriented material. Roscoe Fawcett, the founder’s son and the company’s circulation director, wanted a piece of the comic pie and asked his editor to put together an anthology comic with at least one character like Superman. The editor, Ralph Daigh, turned to staff writer Bill Parker, who created a team of superheroes based on classical gods and led by Captain Thunder. Roscoe worried that kids wouldn’t identify and/or be interested in a group of heroes – he wanted just one character who was a 10 or 12 year old boy, just like his target audience.

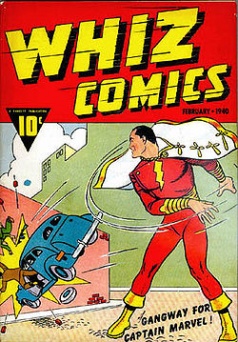

Parker and staff artist Charles Clarence Beck gave Captain Thunder the powers of all the gods they had been using for his teammates, then made him the alter-ego of young Billy Batson, who could transform into the adult hero by saying his magic work, “Shazam!” Next they worked up several supporting characters and stories for Fawcett’s “Flash Comics.” While that was in progress, DC beat them to the punch with its own version of “Flash Comics” featuring a character named Johnny Thunder. The Fawcett team quickly regrouped and changed plans – instead of “Flash Comics” featuring Captain Thunder, they came up with “Thrill Comics” featuring Captain Marvel. Plans changed again when they learned Better Publications had just trademarked “Thrilling Comics,” so Captain Marvel’s book was renamed “Whiz Comics.”

Why “Whiz?” To capitalize on brand awareness. Fawcett’s longest-running magazine was the humorous “Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang.” (Captain Billy was a nickname for Wilford Fawcett Sr, the company’s founder.) Although this title was less likely to be stolen than “Flash” or “Thrill,” Fawcett used the popular practice of using an ashcan copy to secure it.

In the modern world, if a company wants to trademark a product name it files paperwork with the US Patent & Trademark Office notifying them of the “intent to use” the name. Prior to 1946, trademarks could only be secured by actual use in commerce. Comic publishers were in a hurry to snatch up all the good titles and needed a way to skirt this law. The answer was the ashcan. When someone thought of an exciting title, they would mock up a quick logo, paste it on a convenient cover image, and staple it to whatever interior content was laying around (like some previously published pages pulled out of the trash pile – hence the name “ashcan.”) Publishers needed at least two copies of every ashcan – one to submit to the Trademark Office, and one for their files – but sometimes made up to five because you can’t be too careful. The government officials who received the ashcan accepted it as proof that the comic had actually been published and sold, thereby granting the trademark. Whether the officials knew what was really happening but were too busy to investigate, or if they really thought those poorly made comics were selling, I’m not sure.

If a publisher decided to use a trademark they had secured by ashcan, most of them sent issue #1 to the newsstands. Fawcett, maybe because they were new, maybe because they feared an audit, did not. It is generally assumed that they sent an ashcan of “Whiz Comics” #1 to the Trademark Office, then started their regular series on newsstands with “Whiz Comics” #2 in December 1939, cover dated February 1940. The assumption is all we have because no extant copy of “Whiz Comics” #1 has been seen since people began to care about this sort of thing, and the creators involved either forgot or never knew the details behind the numbering.

Continued belowCaptain Marvel was an immediate hit. The wish fulfillment behind a young boy turning into a powerful adult hero with a magic word was certainly part of it, but Captain Marvel was also the first superhero with a sense of humor. CC Beck was made the head of Fawcett’s new comic art department earning $50 per page ($1,063 in 2023 dollars), and he took over as the guiding hand of Captain Marvel when Parker left the company.

Fawcett had hoped for a hit, but weren’t putting all their eggs in the Captain Marvel basket. The month after “Whiz” #2, they put out “Master Comics” #1 starring the superhero Master Man. Master Man was super strong, super fast, and super similar to Superman. DC, who had recently filed a successful copyright infringement suit against another publisher for a Superman knockoff, threatened Fawcett with the same. Fawcett chose not to resist, replacing Master Man with Bulletman in October. Notably, DC didn’t take issue with Captain Marvel at this time.

In August 1940, Fawcett released “Special Edition Comics” #1, a 68-page one-shot containing Captain Marvel stories exclusively. Its purpose was to see if kids would support a comic dedicated to a single character, which was an uncommon way to package a comic at the time. Sales were brisk enough for Fawcett to commit to a new quarterly book, “Captain Marvel Adventures,” starting January 1941. Instead of the usual creative team, Fawcett hired the famous Joe Simon and Jack Kirby to package it. They were even invited to sign their names to it, with Fawcett believing that might help sales to the tune of another million copies or so. The debut issue was released without a number on it, but the April issue came with a number 2.

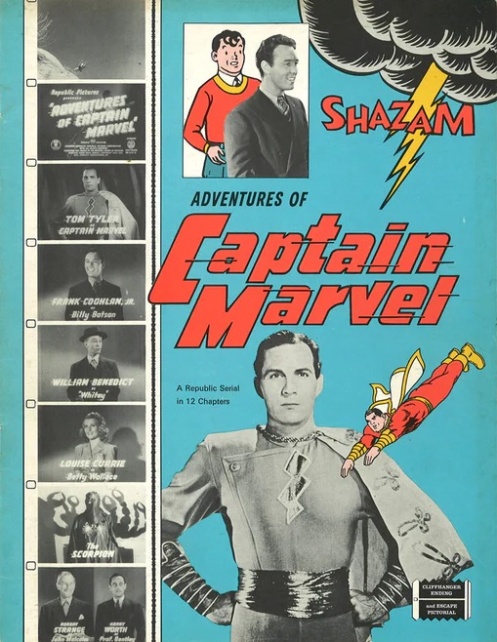

DC wasn’t bluffing. They officially filed suit against Fawcett and Republic on September 5, 1941. This would eventually be an important event in Captain Marvel’s history, but Fawcett had good copyright lawyers and the legal process moved at a glacial pace, so we’ll drop this thread for now to focus on other things, then pick it up again when the chronology catches up to the suit.

Fawcett tried to flex its clout in 1941 with experiments in non-standard formatting. Among other attempts, it released the oversized “Captain Marvel Thrill Book.” The oversized (8.5”x11”) comic had a color cover. Its interior was black and white reprints. There’s no sales data for it, but there’s good reason to think it was a dud – chiefly that there was no follow up. That doesn’t necessarily mean there was no interest from its intended audience, though. Newsstand dealers were often resistant to non-standard formats because they didn’t properly fit in their rack space. That usually meant that if the comic got racked, it wasn’t near the other comics and got overlooked.

In December 1941, Fawcett expanded the Captain Marvel brand into to franchise with the introduction of Captain Marvel Jr. The character first appeared in a three-part crossover between “Whiz Comics” and “Master Comics” before adopting the latter title as his regular home where he had his own adventures. CM Jr. was the first juvenile version of a superhero, in contrast to being a sidekick like Toro, Bucky, or Robin. Although Jerry Siegel had proposed a similar concept with Superboy to his editors earlier in 1941, DC didn’t commit it to paper until several years later.

The multi-issue introduction for CM Jr. was definitely not normal for comics in the early 1940s. The common understanding at the time was that kids wanted a complete story every time, and often more than one per issue. Even if a publisher thought an audience for such stories did exist, newsstand distribution was too unreliable for them to expect every reader to have access to every consecutive issue. There was no back issue market at the time, so readers who missed an issue were pretty much out of luck. The sales and popularity of Captain Marvel allowed him to defy this convention and use continuity in a way other comics didn’t.

Continued belowIn 1943, “Captain Marvel Adventures” did something even more daring. In the February issue (#22, cover dated March), readers were treated to the first part of ‘The Monster Society of Evil,’ an extended epic that ran an unprecedented 25 chapters before concluding in issue #46. It also imported the character Whitey Murphy, a member of the supporting cast from the 1941 Republic Serial, into the comic cannon. Beyond that, there was another extended storyline that began in issue #24, albeit with looser continuity. This one saw Captain Marvel travel the United States with each story set in a different city and populated with cameos from prominent citizens. Each issue naturally received attention from the associated local press corps and boosted regional sales.

Beck later said he believed these extended stories were the main reason “Captain Marvel” overtook “Superman” as the bestselling comic book. When the ‘Monster Society of Evil’ concluded in 1945, “Captain Marvel Adventures” annual circulation peaked at 14 million. Of that massive audience, 573,000 took the time to join the Captain Marvel fan club.

Meanwhile, the comic industry was changing. Superheroes everywhere were bleeding readers. Sales of “Captain Marvel Adventures” fell an average 100,000 copies per month for two years. Monthly circulation was still a healthy 1.3 million, but the trend accelerating in the wrong direction as readers flocked to a new genre. In 1947, “Crime Does Not Pay” surpassed both “Captain Marvel Adventures” and “Superman” as the most popular comic.

It was in this declining economy that the copyright infringement lawsuit from DC finally went to trial. Beyond obvious similarities like both characters being muscular reporters with dark hair, DC offered as evidence a binder full of clippings from Superman comics side-by-side with clippings from Captain Marvel comics showing the characters doing similar things. Naturally, the Superman scenes pre-dated the Captain Marvel ones. The natural response from Fawcett’s council was a binder of their own with a third set of clippings, this time pairing the Superman panels presented by DC with Captain Marvel panels that were even older. They also had panels from Tarzan and Popeye comic strips that were created before either Captain Marvel or Superman. They used that as a springboard to compare superheroes in general to ancient legends and mythology. Superman is, after all, Moses FROM SPACE!

Fawcett’s attorneys didn’t stop there, however. They were copyright specialists, and they went for the jugular. In several instances, Superman had been printed without the proper copyright notices. Therefore, DC had abandoned their claim to the character and thus there could not be any infringement even if DC’s evidence of plagiarism had any merit. The judge was convinced and ruled in Fawcett’s favor.

DC appealed and they were back in court in 1951. The appellate court overturned the original ruling, citing the obvious lack of intent to forfeit the copyright. The judge also said that while Captain Marvel was not an infringement on the whole, it was possible that certain stories could constitute plagiarism. This sent the case back for a retrial on different grounds. In the face of looming defeat, mounting legal costs, and declining profits from sales, Fawcett threw in the towel in 1953 and reached an out of court settlement. In exchange for ceasing publication of all Captain Marvel books and a reported $400,000 one-time payment, Fawcett was off the hook.

Fawcett chose to cut its losses and leave the comic book industry altogether. By this time, publishing comics was marring its reputation anyway. Its non-Captain Marvel titles were sold to Charlton and Fawcett focused on its more profitable paperback business. Captain Marvel’s exit from the stage left only three superheroes still headlining comics in America: Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

Continued belowAcross the pond, sales of superheroes were still going strong in the UK. The company L Miller & Sons had the license to reprint Captain Marvel stories and was doing well enough with it to convert the series to a weekly one effective August 19, 1953, so Fawcett’s capitulation to DC just a couple months later was terrible news. To keep their cash cow going, they changed the title and character’s name to Marvelman. Readers accepted the rebranding, and new content kept it going for decades. When Alan Moore took over the series in 1982 and turned it into a critical hit, Marvel UK sued over the name causing it to change to Miracleman. But that’s a story for another time…

Fawcett’s claim to the Captain Marvel name in the US faded with the character’s disuse, so it was fair game when Batmania hit the nation in 1966. As comic sales rose, a new “Captain Marvel” #1 was released by Country-Wide, the publishing company owned by former comic artist Myron Fass. This series was about a new android character who could cause his limbs to fly off his body and strike criminals when he said “split!” They would return and reconnect when he said “xam,” pronounced zam. (Say the two magic words aloud, split xam, and you’ll get the joke.) Like Batmania, this series faded quickly, leaving only five issues behind.

Fass’s real legacy was in reminding Martin Goodman, the owner of the company now calling itself Marvel Comics, that “Captain Marvel” existed and was unsecured. Goodman ordered Stan Lee to use the name as soon as possible. Lee complied, but wasn’t excited about it so he passed the real writing chores to his second, Roy Thomas. This Captain Marvel went on to have a storied history of his own, but for the purposes of this article, it’s enough to note that Marvel Comics had the trademark on “Captain Marvel” from 1967 onward.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the expectation among comic publishers was that the “lifetime” of a comic reader was about four years – roughly from age eight to 12 – and then they would move on to other media forms. This was mostly the result of the Comics Code Authority, who sanitized comic content to the point only children could be entertained by it. By that math, three generations had passed since “Captain Marvel” had last been printed in the US. If a current reader heard about Fawcett’s great hero, it was from his parent, not his older brother or friend. Captain Marvel had faded from the comic zeitgeist.

In 1965, however, Jules Feiffer wrote the nostalgic “The Great Comic Book Heroes.” This 127-page book was a collection of essays focused on the popular characters of Feiffer’s youth in the 30s. Aside from its uncommonly positive spin on its material, it also reprinted examples of classic stories from Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and the Spirit. Feiffer naturally included Captain Marvel as the most popular superhero of the time, but was unable to reprint a full story. In light of the court case, he wrote to DC, not Fawcett, to get permission to include a sample of “Captain Marvel” for educational and historical purposes. DC allowed him only one page, but it was enough to spark interest among his young readers.

In 1969, a group of comic professionals form the Academy of Comic Book Arts as a social organization. Among other functions, lobbied for creator rights and helped freelancers find work and negotiate better pay. The Academy also created the first comic industry recognition program, which it dubbed the Shazam Awards. The name was likely chosen in equal parts because the adults all recognized the name, and because it wouldn’t show any favoritism toward a contemporary hero or publisher. (Note: this professional organization should not be confused with the The Academy of Comic Book Arts and Sciences, a fan organization from 1961 that created the first comic fan awards, the Alley Awards.)

In July 1972, DC purchased the rights to Captain Marvel from Fawcett with the intention of launching a new series. Their rival’s trademark on “Captain Marvel” didn’t prevent them from publishing a story about a character with that name, it only meant they needed a new title. That was easy enough. “Shazam” #1 was soon on the schedule for February 1973. Hoping to recapture lightning in a bottle, they brought in co-creator CC Beck to do pencils for new scripts by Denny O’Neil.

Check back next Monday for the rest of this story.