Last week, we ran an article providing an abbreviated history of underground comix. It covered the decade or so when the undergrounds were at their peak popularity, and explained how they were largely a reaction to the Comics Code and the narrowing effect superheroes had on comics publishing. The books were created mostly by men in their early twenties and easily recognized for their crude and vulgar content. As noted at the end of that article, underground comix faded away for a variety of reasons, but their creators didn’t. Instead, they matured and moved on to a different type of comic. One that was so different from the undergrounds, people needed a new name to describe them. One cartoonist, Mike Friedrich, coined the term groundlevel, but it never quite caught on. Instead, they became known as Alternative Comics.

Naturally, this wasn’t a clean transition, and the term was applied retroactively to books after the shift had occurred. Like the undergrounds, alternative (or simply ‘alt’) comics were set apart from mainstream content by their target audience (20+ adults), their higher production quality, and their black and white art. Similarities aside, alt comics differed from undergrounds in two major ways. First, while underground comics had focused on shocks and rule breaking, alt comics made a concerted effort to have meaning and value. Second, and deriving directly from the first, was a greater acceptance of alt comics in the fast growing number of comic specialty shops, a place where underground never made much headway. When Phil Seuling and his Sea Gate Distribution turned those shops into the direct market as it’s known today, the alternatives had large industry access without large industry costs.

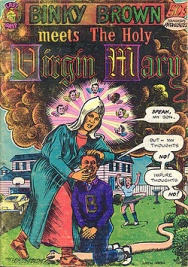

From this narrow perspective, the first prototype for what would later be considered an alt comic was Justin Green’s “Binky Brown meets the Holy Virgin Mary,” published through Last Gasp Eco-Funnies in 1972. Through Binky Brown, Green shares the conflict between his Catholic faith and his sexual desires as an adolescent. This 44 page story is pretty much universally categorized as an underground, but it’s also considered to be the first autobiographical comic, a major genre in alt comics. “Binky” is also cited as an influence by later alt comic creators.

Three years later, underground veterans Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith released “Arcade: The Comics Revue” through the Print Mint. This anthology was printed from 1975 to 1976 for a total of seven issues. The mix of traditional underground content with attempts at genuine storytelling leads some sources to describe it as the ‘last stand’ of underground comics. The book was intended to be a “comics magazine for adults,” but it was ahead of its time and poorly received. When it ended, the internal strife of editing his peers led Spiegelman to decide he would never helm an anthology again.

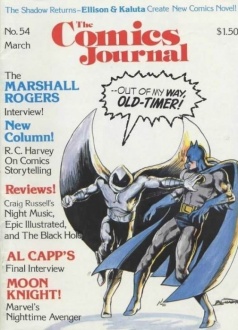

The same year “Arcade” was ending, an influential force in alternative comics was starting. Before 1976, there was one major magazine about comics – Alan Light’s “The Buyer’s Guide”. It had been around for five years and was the primary source of comic news for most readers. Because of the shape of the industry at the time, “TBG” also had a heavy focus on mainstream comics.

There was another magazine with a broader focus and smaller circulation, “The Nostalgia Journal”. It was about to fold when Gary Groth and Mike Catron took over publishing in July 1976 with big plans to revive it. Beginning with issue 27, the name was changed to “The New Nostalgia Journal” and was published through the duo’s newly-created Fantagraphics company. Before, it had covered a wide range of collectables. Now, its subject matter reflected the interests of its new owners – comics. The name was changed again for issue 32 (Jan 1977) to broadcast this content shift, and “The Comics Journal” was born. “TCJ” quickly became known for extensive interviews and editorial content. Groth is very open about his dislike of corporate comics and his interest in promoting more literary work and creator rights. As more alternative comics became available in the early 80s, the “Journal” was instrumental in supporting the movement.

Continued belowAlso in 1976, a nineteen year old Terry Nantier partnered with two friends to start Flying Buttress Publications. Nantier was an American citizen who had lived in Paris for a few years, and while there he had grown fond of European comics. When he moved back to the US, he wanted to share these comics with others. Through the Flying Buttress (later renamed NBM Publishing, the initials representing the three founders: Nantier, Beall, and Minoustchine), Nantier published English translations of popular comics from across the Atlantic. They retained the graphic novel format of the comics, which was quite different from the 32 page saddle stitched pamphlets Americans were used to reading. Another company, Catalan Communications, would also make European graphic novels available in the US after its founding in 1983.

At the end of 1977, a 21 year old high school drop-out named Dave Sim published “Cerebus” #1 through the Aardvark-Vanaheim imprint with his then-girlfriend Deni Loubert. It starred an anthropomorphic Aardvark and was initially a parody of Conan the Barbarian. During a period of heavy LSD use in 1979 that led to hospitalization, Sim was inspired to declare “Cerebus” would be a 300 issue series. This would be a bold claim from any small press creator at any time, but it was doubly so for a 23 year old drug abuser. There were set backs over the next 27 years, but Sim was able to fulfill his dream on time in March 2004. Along the way, “Cerebus” left its parody status behind and tackled a wide variety of topics. Sim and his creation were (and are) an inspiration to many notable creators.

In February 1978, two months after the launch of “Cerebus”, another alt comic sensation made its way to readers. “ElfQuest” was the brainchild of Wendy Pini (neé Fletcher), a 27 year old San Franciscan. It was published by her husband Richard Pini, an MIT alum she met through the letters page of the original “Silver Surfer” series. She had been working on the story for some time, and they decided to self publish after being turned down by both Marvel and DC. “ElfQuest” was a fantasy series that grabbed the attention of many female readers. Collected editions were sold in bookstores in addition to the direct market, which also helped the series reach a wider audience. At peak popularity, “ElfQuest” was selling in excess of 100,000 copies.

The Pinis named their imprint WaRP Graphics (it’s an acronym for their names, hence the odd capitalization), and at the time they were just trying to find a way to print Wendy’s comic. The idea to turn their imprint into a real company didn’t settle in until two years later, when “ElfQuest” was successful enough for them to consider their position. Richard quit his job in 1979 to publish full time, and WaRP would eventually publish other comics, like Colleen Doran’s “A Distant Soil” when “ElfQuest” took a hiatus in the mid eighties. Richard would later described the hiatus and the diversification as bad decisions, and said that given the chance to do it over he would hire freelancers to expand the ElfQuest universe instead.

In 1980, a revolution in comics would begin with the publication of “Raw”, a new anthology put together by Art Spiegelman’s wife, Franḉoise Moully. This publication immediately drew extra attention to alternative comics because several issues included work by prominent New York artists. Critics and art aficionados following the work of these established artists found themselves reading the other comics in “Raw”, and they were surprised by the quality. One story in particular, Spiegelman’s “Maus”, really caused them to take notice.

“Maus” began as a three page strip in 1972, but the work didn’t really began to take form until 1978. The story is an anthropomorphic autobiography telling the story of Spiegelman, his relationship with his dad, and his dad’s experiences during the holocaust. Once Spiegelman had enough to print, he found he had nowhere to print it. He was still opposed to running a new anthology after his experience with “Arcade”, but his wife was more than happy to do it for him. Relieved of the editing responsibilities, he serialized “Maus” through the 11 issues of “Raw” printed between 1980 and 1991. (They were almost, but not quite, annual issues.)

Continued belowThe first half of the story was collected into a trade by Pantheon Books in 1986. When deciding the size of the print run, no one expected the book to do any better than Pantheon’s average book. It didn’t take long for everyone to realize the significance of “Maus” though. At an early book signing, the line for Spiegelman’s autograph literally went out the door, down the street, and around the corner. Some of the response to the book (and Spiegelman’s emotional reaction to it) found its way into the second volume. After the whole story was completed in 1991, it went on to win the Pulitzer Prize.

In 1982, six years after Fantagraphics began publishing “The Comic Journal”, they released their first comic book: “Love and Rockets” from the Hernandez brothers. This critically-acclaimed debut was soon followed by Dan Clowes’ “Eightball”, Peter Bagge’s “Hate”, and numerous other titles over the years. Like “Cerebus” before them, nearly all of Fantagraphics’ early releases are listed as influences by modern comic masters.

In April of the following year, Steve Gallacci’s Thoughts & Images imprint released “Albedo Anthropomorphic” #0. As you could probably guess from the title, this anthology featured stories about humanized animals. These types of stories were quickly becoming a fad, and the sold-out issue went through three printings to satisfy demand. Its price spiked when it became a back issue, and this was one of the earliest signs of the coming boom times for the comic industry. The second issue was released in November of 1984, and featured the first appearance of Usagi Yojimbo. Amazingly, this issue had a print run of only 2000 copies, and it too became very hard to find after selling out.

Between those two issues, a cultural phenomenon was blossoming. Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird were in their early twenties when they came up with the idea of anthropomorphic turtles who were trained in the martial arts. After playing with the concept in-house for a while, they decided to make a real effort at turning it into a comic. The two pooled their savings, their tax refunds, and some borrowed money to print 3000 copies of “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” #1 in May 1984. There was enough money left over to run an ad in “The Buyer’s Guide”, and they planned to sell all 3000 copies by mail order. The ad generated unexpected demand, and retailers began calling their distributors to see if the book was available to order. The distributors, in turn, contacted Eastman and Laird seeking to carry the book. All of the profit from the 3000 copies was used for a second printing of 6000 copies. Word of the book continued to spread, and orders for the third issue came in at 55,000. Eastman and Laird were quite surprised by the sudden success. Even with the unexpected sales of the first issue, they still expected demand to fade away. At first, they replied to every fan letter they received with a handwritten reply and a sketch in an effort to retain readers.

The runaway success of “TMNT” led to a spike in prices for back issues. It also led to higher demand for other black and white books which could conceivably-one-day-maybe become valuable. Today, this era is known as the “Black and White Boom”. Publishers realized the sales potential, and in no time the market was glutted with new B&W titles starring fighting animals, usually with titles made up of three adjectives and a species. The sales potential was also clear to retailers, and shops that hadn’t been interested in stocking even the most popular alternative comics were now shelving as many as they could handle.

Going back to the dawn of the Underground Comix movement, small press books have always been priced higher than mainstream books. This hasn’t been motivated by greed, just economics. The fixed costs of producing a nationally distributed mainstream comic can be spread over a much wider readership than a local book with 1,000 readers. That’s also why nearly all of the underground and alternative comics were black and white – cheaper to print, and one less person to pay (or less time-intensive for the artist).

Continued belowThe effect of the B&W boom on the industry as a whole can be seen in the median price of a comic book. In 1984, the year “TMNT” debuted, the median price for a comic was 75 cents. In 1986, it had jumped to $1.25. In 1987 it was $1.50. In 1989 cover prices crept up to $1.75, a full dollar higher than it had been just three years earlier. A jump of a dollar may not sound like much in today’s era of $4.99 single issues, but that’s an increase of more than 100%. It was also hard to stomach for younger readers on the strict budget of their weekly allowance.

The boom gave a boost to established publishers from the Underground era like Rip Off Press, who had a hit with their “Miami Mice” book. The boom also prompted the creation of several new publishers vying for a piece of the growing pie. Among the many forgotten, like Apple Comics and Pied Piper Comics, are a few that stuck around: Dan Vado’s SLG, Dave Olbrech’s Malibu, and Mike Richardson’s Dark Horse. From very humble beginnings, Dark Horse rose above its small press peers to become the third largest comic publisher in America. That story is too long to include here, so a separate article chronicling Dark Horse’s successful growth will be up later today.

1986 was also the year the B&W boom reached a crescendo. Everyone involved from publishers to readers were beginning to realize the excess (read: silliness) of the boom. It didn’t help that at the same time, DC put out Frank Miller’s “Batman: The Dark Knight Returns” and rebooted Superman’s origin in John Bryne’s “Man of Steel” miniseries. These high-profile books pulled readers back to mainstream titles, further diminishing the sales of alternative comics. By 1987, the sales on all alternative comics, good and bad, had fallen at least 25%.

Some publishers and retailers went out of business because of this B&W bust. Others held on the few years to see the next big comic boom that started in 1989, this time boosting the superhero side of the market. The same opportunism that brought new small publishers to the alternative comics game would prompt a rise in superhero books from small publishers.

But…if the small press are making mainstream material, then they aren’t really alternative comics anymore, are they? This new shift in content would once again change how readers talk about the small press. Instead of reading alternative comics, now they’re reading Independent comics. I’ll tell you about those next week.