Welcome to the second part of our three-part look at variant covers and the history behind them. Yesterday, I told you about the earliest books with multiple covers and how they developed naturally out of publishing necessities. Today, we’re going to look at the other end of the spectrum: when they’re spawned by marketing and are pushed to the limit.

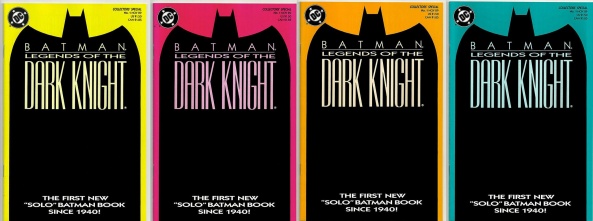

Despite the show of demand for rare covers like the Superman Comics editions of “Justice League” and “Firestorm,” publishers didn’t respond and two full years passed without a cover variant. Then, “Legends of the Dark Knight” #1 was solicited to coincide with the Batman film in 1989. It was to be the third title featuring the caped crusader, and was the first new one in half a century. Needless to say, fans and retailers were excited. So excited were they, in fact, that the number of orders coming in scared Bruce Bristow, DC’s Vice President of Marketing. It seems he didn’t think the market could handle that volume of Bat books.

The decision was then made late in the game to release the first issue with four covers. Fans loved it, and many people bought multiple copies to have a complete set.

To understand what happens next, we first have to go back to the Silver Age of Comics (generally accepted to have begun in 1956 with “Showcase” #4). The kids who were reading comics during then and throughout the 60s were the first generation to be recognized as “teenagers” and actively pursued by advertisers. Comics and sports trading cards were two of the many avenues of leisure pushed on this new demographic. A small percentage of teens maintained the hobbies as they aged, but most of them moved on and their collections were lost in various ways.

When this generation reached middle age (which happens to be right around the mid 80s), there was an unheralded nostalgia boom in the United States. Former card and comic collectors sought out items from their youth, and demand quickly outstripped supply. As prices rose, more people heard about it and thought to themselves, “I used to own that book! If only I had kept it, I could sell it now for lots of money!” This mentality was fueled by greed, ignorance of basic economic principles, and encouragement by people who should have known better.* The result was the rapid formation of a large speculator market.

(*We joke nowadays about putting your kid through college with a comic book, but in the early 90s, reputable firms like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times ran articles treating comics and cards as viable investment alternatives to stocks or bonds. Sometimes they still do. Seriously, read that link; It goes from the outlandish “a comic book could pay off your house” to outright lies such as “comic-book valuations have yet to decline” with a straight face. And it’s from 2013.)

Remember when I mentioned baseball cards earlier? The nostalgia boom hit that industry first, and card shops proliferated throughout the country. As the fever spread to comics, many of these card specialty shops began selling comics in an effort to make a quick buck. Unfortunately, the reason the card shop owners originally sold cards instead of comics is because they knew about cards, not comics. The combination of uninformed retailers with uniformed buyers was a dangerous powder keg that could not be sustained.

The next piece of this puzzle was behind the scenes at Marvel. In a case of the most unfortunate timing, just as this speculator market was forming, Marvel was working to be listed as a publicly traded company. When it became beholden to its stockholders in July 1991, the company was under a mandate to continuously beat its previous quarter earnings, leading to excessive gimmicks and unnecessary price hikes.

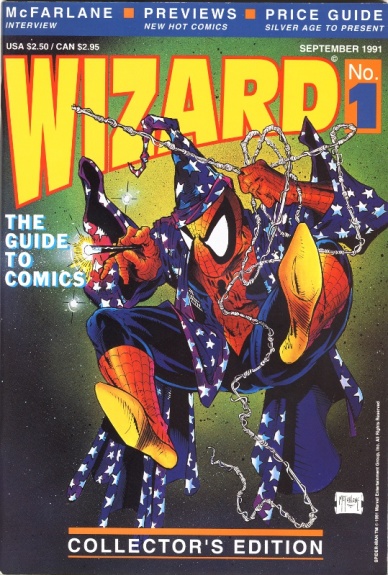

Finally, Wizard magazine began monthly publication in September of 1991, including a price guide with issues as recent as they could manage with their publication schedule. As Wizard became more commonplace, it supplanted the annual Overstreet guide as the standard. While Wizard did run plenty of articles about the dangers of speculation in the market, at the same time it made the market worse. By highlighting their “hot” books, Wizard acted as a map for uninformed speculators who were always chasing the next big thing. Promotion for comics in Wizard would become a self-fulfilling prophesy because, as noted in court case from part one, if the guide said the price of a particular issue was going up, then speculator demand for that book would rise and prices would follow.

Continued belowThe result of this confluence was a rapid response to the success of “Legends of the Dark Knight” catering to the speculator market. At the time, variant covers went hand-in-hand with enhanced covers. Just a few months after “Legends of the Dark Knight” debuted, Marvel released “Spider-Man” #1 with 13 cover variations, including enhancements and polybags, and it set a sales record. In April 1991, “X-Force” #1 was polybagged with a trading card and broke that record. In June 1991, “Silver Surfer” #50 received a foil embossed cover and went through three printings. In August 1991, “X-Men” #1 was released with five covers and set another sales record. “Ghost Rider” #15 was released with a glow-in-the-dark-ink cover, proving a comic didn’t have to be a number one or an anniversary to benefit from a cover gimmick.

Most of this was the work of Richard T. Rogers, a marketing consultant Marvel hired to help them meet their mandate. To be fair, the marketers weren’t out to take advantage of anyone, they were just doing their job. Aside from real milestone occasions, most of the creators and editors at Marvel hated these gimmicks, and worked hard to make sure there was a ‘plain vanilla’ version available for readers who just wanted the story. And if you think Marvel put out a lot of variant and gimmick covers during the boom, writer/editor Danny Fingeroth wishes you could see how many they didn’t do.

It definitely wasn’t just Marvel who was guilty of pushing style over content. DC experimented with holograms on the covers to “Robin II.” Valiant became infamous for their chromium covers, and Defiant put out a #0 issue that was made by assembling a complete set of trading cards.

Speaking of cards, countless comics came packed with a trading card or some other type of premium. Sometimes one comic would be paired with more than one card, forcing a collector to buy multiple copies to get all the cards. Incentive covers were around at the time, but were not especially common. Speculation wasn’t just limited to the buyer side of the business, either; numerous publishers rose and fell during those years, including Malibu, Topps, and Milestone.

It was truly a bizarre era for the hobby, and one which is now viewed with derision from fans. Some of it is earned, some not. Many good stories were told during the boom, and their home in today’s quarter bins have less to do with the quality of the work than the quantity of copies produced. When the inevitable crash came, it was not unexpected; retailers and readers who predated the boom had predicted the crash from the beginning. When the speculators left, so too did most of the material marketed toward them. Enhanced covers vanished from the shelves, and there was a sharp reduction in variant covers, although they never quite disappeared.

In 1996, Marvel put out two versions of the first issues in their Heroes Reborn line. In 1997, “The Darkness” celebrated its eleventh issue with eleven covers. In November of 1999, Top Cow surprised retailers with variant covers on all of their reorders. Also in 1999, DC began giving retailers who participated in their Retailer Representative Program exclusive covers; in 2000, “Ultimate Spider-Man” debuted with a 1:100 incentive cover, which was considered outrageous by many retailers at the time. But in 2002, Dreamwave relaunched “Transformers” with a 1:10 incentive cover, and “He-Man” did the same two years later. There were other issues released with multiple covers during this time, but they were always the exception, not the rule.

Until they were again. I’ll get into that tomorrow, in The History of Variant Covers Part 3: The Modern Era