As you may have read earlier, we as reviewers can do a lot to improve the valuation of artists in comics today by talking about comic art a little bit differently. It’s a difficult thing to do. I should know, I’ve reviewed for Multiversity for years and have screwed up as much as I haven’t. But we’ve worked very hard to do a little bit better, and we want everyone to do what they can to do the same.

With that in mind, we’ve created a living document about what reviewers should look for when they are talking about comic art. This includes ideas and perspective from Multiversity, as well as insight from artists like Declan Shalvey, Sean Gordon Murphy and Gabriel Hardman. We want this piece to grow, and if you have additions you’d like to make, whether it is a link to a useful article or just things you think reviewers often miss, we’ll gladly take it into consideration as we update this piece.

This by no means is meant to diminish what comic reviewers do, as we know many of you are unpaid and write about comics strictly because of the passion you have for them (we know about that all too well, too). And we certainly aren’t saying Multiversity is some sort of artistic utopia, as we still have our own growth to make. This is just us saying, “let’s get better together.” We hope you enjoy, and we hope this helps.

– It’s a story first: Reviewers often treat writers like the primary storytellers, but so much of the story – from the pacing and mood to the subtle bits that elevate the material – is created by the artist. The story isn’t a writer telling the story, but the writer and the artist doing that together. When a moment really clicks, like the final interactions between Joacquim and Forever in “Lazarus” #4, it clicks because of those two creators working in concert, not because of the writer singlehandedly making a moment work.

– Style second: It’s one thing for you to subjectively not like someone’s art. I’m going to be totally honest, Howard Chaykin is an artist that I do not enjoy from a stylistic point of view. However, reading something like “Satellite Sam” shows him as someone who is an exceptional storyteller, and when weighing the power of the art, you need to remember that the way you personally interact with the work is a secondary consideration.

– Don’t assume: As readers, we make a lot of assumptions about how stories come together that maybe we shouldn’t. As reviewers, you should not do that, because honestly, we have no idea how this specific sausage was made. Did you love a certain part? Don’t say something along the lines of “Writer X did an amazing job of making us care about the lead when Y happened.” We have no idea if that was Writer X or Artist Z, who is probably annoyed that he/she didn’t get any credit.

– Clarity is key: Does an action sequence make sense? Can you distinguish between supporting characters? Can you follow the panels and the page to tell the story? If the answer is no to any of these things, the book likely suffers for it. Clarity in art is a broad idea, but an important one to bring up when talking art.

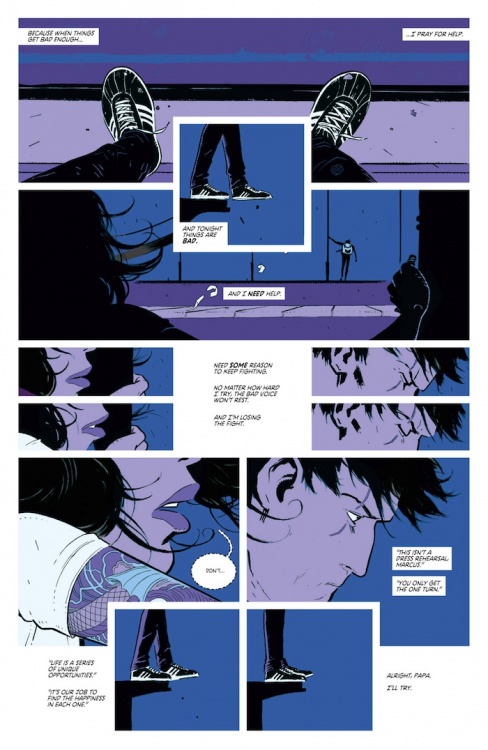

– Look for the layout: When it comes to paneling and page layouts, they aren’t just random decisions. A lot of thought goes into every page and every panel, as you can see in every book from “Watchmen” to the smallest of releases. Were there any notable choices made? What stood out? What didn’t work? A lot can be derived from the choices that were made in terms of layout, and it is those choices that can affect anything from pacing to scene emphasis.

– In the ghetto: While we are often guilty of this ourselves, art analysis does not belong at the end of every review. We don’t need to create a second-to-last paragraph ghetto for art review just because we don’t know what to do with it. Mix it up, lead with your art section, put it in the middle, or better yet, weave it into your discussion about the story and issue itself. As we said above, they are one and the same.

Continued below– Colors and mood: Color in comics aren’t simple choices, but integral ones that can be as important as anything else in the comic. Books like “The Manhattan Projects” have made color a story aspect, and by omitting mention from your reviews, you’re doing a disservice to the gifted artists who color books.

– Avoid buzzwords: “Detailed art.” “Clean lines.” What do those even mean? When you’re writing about art, don’t lean on terms that sound nice but ultimately don’t mean much of anything. That’s lazy, and it’s not just Robin Williams in “Dead Poet’s Society” who is not a fan of that.

– Don’t forget the cover: There is one highly prominent piece of art that goes virtually untouched in each and every issue: the cover. Now, obviously this is different than the interior storytelling, but covers often are often incredible, engaging pieces of work with a story in them (see: Yuko Shimizu’s work on “The Unwritten”). If something stands out about this work, factor that in where you can.

It’s one thing for Multiversity to give suggestions, as we’re just a bunch of schlubs on the Internet. Don’t take it from us though, listen to the artists themselves, as three of the best around contributed some tips on things reviewers can look for and questions they can ask themselves when they are writing about comic art. Take a look below.

Declan Shalvey: When films are reviewed, they don’t talk about what the screenwriter did for most of it, then mention the director at the end, nor do they spend most of their time telling you the entire story of the film. The art team is responsible for the look, tone, set design, light design, shot choices, composition, etc.

Have I reviewed this comic as a piece of art, or have I only explained what happened in the issue, therefore defeating the point of anyone reading it as an actual comic?

Why did I only mention the artist in the last paragraph? Way more time was put into illustrating that comic than there was in writing it.

How many panels are in this page? Two? Five? Why is that?

Story flow; where and how is the artist moving you around the page? Why is he/she doing that? What’s the biggest panel on the page? Why is it so big; is it the focus? Why is that panel so important? Did I follow the story ok? If not, what tripped me up?

Did I notice the colour palette? Was colour used for storytelling purposes? Are there any identity colours for characters? Are the colours linked to each other in any way? Do the colours inform the mood of the page?

Why is a character breaking a panel border? Is it serving the story or just gratuitous and distracting from the story?

Are there any noticeable compositions? Do they add mood or character?

Gabriel Hardman: The biggest thing comics reviewers need to understand is that they’re already reviewing the art. Storytelling and art can’t be separated in comics. There’s no other way to know what’s going on. If you’ve read a great story that’s not just down to the writer, the artist is equally responsible for telling that story through the visuals. It’s that simple. Art in comics doesn’t equal pretty pictures, it equals storytelling.

And reviewing art isn’t about the surface style of the drawings. That’s a minor subjective component along the lines of the writer’s dialogue style.

I’m coming at this as a writer and artist. I write for other artists as well as for myself and I know how important the art is to telling a story. If it’s not getting an idea across visually, that will sink the book. But if you can articulate a idea through images — create a third idea through the marriage of words and pictures, that’s the magic of comics.