In terms of structure, the Bible offers perhaps some of the most complex storytelling to date. Whether you take its text at face value as nothing but a story or find that the words inside inspire and enrich your life, there’s no question that the Bible overall is a very uneven narrative, offering a strange ebb and flow between the characters within and their relationship with the all powerful being that controls the universe. At times, God remains a very present figure or character, speaking to some of his prophets and acolytes directly, while at others he leans more towards the background, speaking through others and allowing for his commands to be interpreted. As a result, the end product exists as a way to seek both personal fulfillment and explore big, existential quandaries of the universe, but that doesn’t change the overall product from being a rather strange and oddly paced read for those attempting a direct approach.

This is made abundantly clear with the story of Noah. The story of Noah is perhaps the least believable yarn within the text, the story of a man who is forced to take on the impossible task of collecting two of every animal so that the world could be drowned and survive on in-breeding. The story of Noah stands out from the rest of the Bible in terms of its believability, and this is in a text that features talking bushes on fire with no irony. Those who study the text generally relent to the notion that everything else in the Bible could’ve happened, perhaps, if that’s the sort of thing you place faith in, but the story of Noah’s ark doesn’t line up with ideal aspects of reality, if only from a generational standpoint. Add to that five or six different interpretations based on different religious texts and historical angles and Noah’s ark is perhaps the most fictional story of the entire Bible.

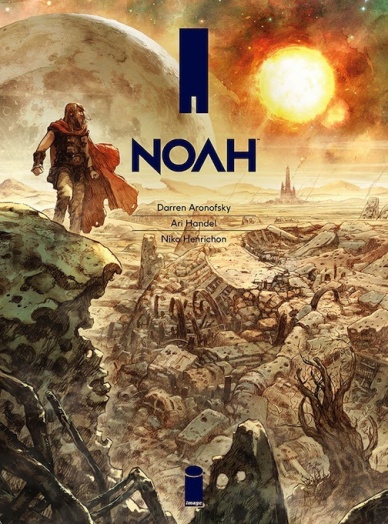

It is with this in mind that we focus on Darren Aronofsky’s “Noah,” translated into graphic novel form by Niko Henrichon. Co-written with Ari Handel, who has worked with Aronofsky on all of his movies save Requiem, “Noah” is the story of a rather tragic man on an otherwise dead world who is plagued by prophetic dreams that offer many questions but no answers. Surviving in a harsh landscape that has been ravaged and decimated by warring tribes of humanity, Noah finds himself and his family on a journey to find not only what the dreams mean, but how to stop and in turn appease them, resulting in the familiar legend of Noah and his ark.

What “Noah” is not is a book mired by its religious intent, as becomes very clear rather quickly. In fact, it’s perhaps easier to call “Noah” an introspective sci-fi thriller than it is a modern interpretation of the Bible, though it does manage to be both in different ways. “Noah” seems like the type of book that could perhaps offend the more devoutly religious, offering up a more mixed idea of a story that has had numerous interpretations and translations, but its aims seem to be somewhere more in the middle ground of theological discussions and apocalyptic drama.

In terms of offering up an accessible story for the non-religious sect out there, “Noah” does a rather excellent job of blurring the line between that which relies implicitly on faith in a higher power and that which is very clearly a fiction. There’s certainly an ever-present spiritual aspect to “Noah,” that is undeniable, but it’s never quite over-powering; instead, it offers up an angle through which we can connect with Noah and understand him on a more personal level. Even if you don’t have faith yourself, it’s easy to identify with Noah’s, who is presented here as a rather broken man, someone who doesn’t quite understand his place in the world but finds purpose in faith and the task given to him of building the ark and caring for its inhabitants. For him, this is more about duty and how this honors God than it is blindly accepting faith, and its through the unquestioned devotion that he ultimately arrives by the end of the story, something that leads to a rather disturbing climax, that we’re offered up a compelling variant on a classic tale.

Continued belowSee, while Noah’s devotion to a higher power may be given a particularly narrow idea of what faith means, at least to him, the greater narrative never does so much as to put as direct a claim on the idea of faith. Faith is a very present aspect to the story because of course it is, but it is interpreted through multiple different ways and multiple different characters. Noah himself goes through a few different iterations of what faith means, at times questioning the logic of the flood event and then questioning further its repercussions; Noah is both the hero and the villain of the story, and it’s important to understand and acknowledge his role in that regard. As such, the places that his faith takes him to is something we question as well, because we can’t help but view the events of the story from such a removed place that logic seemingly overpowers our judgement, which is something Noah does not ultimately allow for himself up to a rather impactful breaking point. We’re allowed to access faith through different means — faith in a higher power, in humanity, in Noah — and it gives the book a few different and interesting angles through which to be read.

What “Noah” ultimately has to say about religion seems in support of open and honest questions. It’s kind of beautiful, in that regard; looking at it from a more removed perspective, the ideas presented in this book speak more towards agnosticism than an advertisement of religion, or even a snide angle towards atheism. “Noah” seems comfortable in asking big questions and then offering no explicit answers, instead relenting to the fact that it all comes down to a personal place — and our direct connection to Noah as the central figurehead, his rise and his fall, the way that he directly connects with his human brothers and sisters but slowly finds himself more and more removed, offers up a very unique perspective of a prophet who essentially fails to be a proper messiah.

Noah is essentially a failure, but his struggle and his journey is incredibly fascinating, no matter your personal spiritual level.

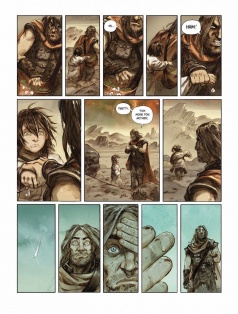

What “Noah” does an excellent job of, though, is making the story of Noah feel less like an impossible fiction and more like a believable journey. It’s a story that finds a more realistic place within the scope of other popular Biblical tales, even with so many fantastical and unbelievable elements within. The story itself blends different interpretations of the flood event into one, utilizing other stories from the Bible to feed into the greater narrative and ideas presented about humanity and its relationship with its creator. We’re given Adam and Eve, the fall of Sodom and Gamorrah and the presence of angelic archetype creatures that assist Noah in his task, mixing demons and legendary Biblical villains into the narrative to create cohesiveness to it all. Noah, his family and peers also seem aware of the sheer ludicrous idea of the flood, critiquing the endeavor, and the story offers quite a few foils to Noah and his actions that creates a very self-aware story, to the extent that while the general yarn may be familiar to most, it’s ultimately different enough to offer something ostensibly new, something different.

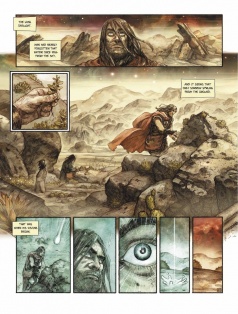

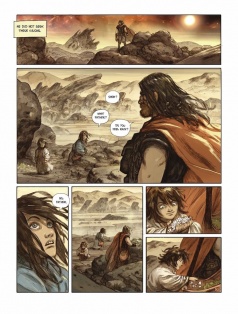

It ultimately boils down to a very human story, albeit a raw and perhaps unnerving one, and one that has a strong emotional core. Noah and his family are varied, as are those that surround them, but they all feel rather real. Noah himself is obviously the most well developed character, but his family and antagonists all get various moments to shine throughout, challenging Noah and both his and our beliefs in unexpected ways. This is not just the story of one man and his responsibility to the fate of the world, but rather that of a family put in a very strange and difficult situation during a rather dark and difficult period. The world presented is not a friendly one, and is in fact a world almost begging for ruin. We find ourselves at the end of the world in a rather unique way, and we’re forced to ask difficult questions alongside myriad struggles.

Continued belowNot only that, but to ignore the more modern and culturally relevant aspects of the book feels like a disservice. There is a lot of text within the book that feels very self-deprecating to modern behavior, with a good deal of meta commentary about decadence and current inhumane behavior. The general gist of “Noah” is that while the book ostensibly takes place years in the past, it also shows a dystopic mirror of the present or near-future. That’s perhaps the most interesting aspect of “Noah,” in fact; while some might find the more charged ideas of the book to be off-putting, even more so than the religious aspects, the book could conceivably represent the future as much as it takes place in the past. It could even take place on another planet. “Noah” strives to be a timeless interpretation of the original story, using the original idea as a call for a more humane approach to modern life. It succeeds fairly well in offering up something that is all at once a Biblical reinterpretation, a satiric look at human nature and at times a dark and intense blockbuster sci-fi thriller.

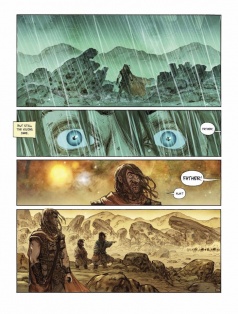

Of course, the book would not be half of the quality that it is without the explicit involvement of Niko Henrichon. I can’t speak to the quality of the movie itself, but as an illustrated adaptation of the screenplay the book is undeniably beautiful. Throughout the book’s four chapters, Henrichon is able to display vast and intensely different landscapes and spaces. The book offers up a wide platform for Henrichon to explore, and the art of the book wonderfully mirrors Noah’s disposition throughout in a way that truly serves the narrative value; as the book begins we’re treated to many wide open and barren landscapes, matching Noah’s own opinions on the world and belief, but as the book continues on and Noah’s beliefs solidify, the book becomes more intimate and close, stuck in the halls of the ark with the same tense nature of the hallways of the Nostromo in Alien.

It is also perhaps worth noting that Henrichon’s depiction of Noah is ostensibly more compelling than what Russell Crowe or any of the cast is perhaps capable of — which is saying something. This isn’t to bash any of the talent involved in the film, but through his singular vision Henrichon is able to deliver an incredibly cohesive and distinct interpretation of the cast, their emotions and their foibles. Against the talent of actual people, Henrichon delivers an incredibly believable approach and cast to a book that is rather far removed from any kind of flattering portrayal of humanity; alone, Henrichon gives us a wide and varied take on the characters and things that make up the narrative, ranging from entire brutal armies of man to the more unbelievable characters and creatures that exist in and around the ark itself.

Henrichon’s adaptation of “Noah” is an incredibly powerful one, and I would imagine that for many it will stand as the definitive interpretation of Aronofsky’s script over the film. While the quality of the film can not (at this time) be discussed, there is something all the more enticing about the idea of Henrichon’s “Noah” than one that is actually acted. Perhaps its the sheer capability of the graphic medium, the fact that there is no budget or use of awkward CGI; perhaps its simply the singular approach to the entire world that allows for a more even-keeled iteration of the story. “Noah” itself is a very intriguing and compelling story about a man with an impossible goal that has devastating repercussions, and giving the translation of the story to such a talented and focused singular vision like Henrichon’s seems like the greatest boon afforded to the story. The time Henrichon has spent in this world and with these characters is palpable, and it reflects off the pages in a wonderfully visceral fashion.

But most importantly, what Henrichon does in the book feels incredibly honest and sincere. There is a level of truth that Henrichon brings to “Noah” that can only be afforded within this medium; the time we spend with the art allows for a deeper comprehension and appreciation of all that the story contains, and the ideas of faith that are present in the text reflect back to us in entirely unique ways. As hyperbolic a statement as it is, Henrichon’s artwork is the closest we will get to seeing the aspects of God important to Noah and his journey reflected accurately and authentically, and that’s “Noah’s” (and Henrichon’s) greatest success.

Continued below

I’ve not seen the film. I do not know what stays the same, what differs or how any of the actors fare in their performances. But, having said that, I’ll also say this: should Noah the film be anything like the book, it will make for some rather good cinema, perhaps akin to what Aronofsky attempted to do with The Fountain. The commercials for it so far have been incredibly misleading, but “Noah” is a very thoughtful look at man, his nature and his behavior in an entirely improbable situation. This is religion poured through a more contemporary lens, an idea of scripture that doesn’t take its fable at face value but instead explores the reasons and logic behind that which one would place their faith in.

However, like with The Fountain, there does lie the danger of having ideas too big and to unwieldy for the limits of cinema, or at least the limits of Aronofsky as a cinematic storyteller. So, just like “the Fountain” illustrated by Kent Williams, I would imagine that many fans of Aronofsky, theology and the questions we ask ourselves day to day about how to live will find a lot to appreciate in Henrichon’s graphic novel version of “Noah.”

“Noah” is available now from Image Comics. You can find a full preview of the book here.