The reviewer’s folly in trying to capture what Seth’s “Clyde Fans” is about: it’s about what cannot be captured.

Seth, celebrated Canadian cartoonist of “It’s a Good Life If You Don’t Weaken” and “Wimbledon Green,” has finished a tale whose first volume, Clyde Fans Book One, came out fifteen years ago in 2004. This completion has been long awaited, and a long wait seems appropriate for this story. The complete Clyde Fans is now a Drawn + Quarterly, slipcase-and-hardback, 476-page graphic novel epic that you can read in one sitting, even though the opus took Seth decades to finish. As a monument to cartooning, fans will collect this on their shelves to re-read, to breathe in again for a hit of that certain feeling at that certain point in our lives, a feeling inevitably haunting and elusive.

Written and Illustrated by SethClyde Fans by SethTwenty years in the making, Clyde Fans peels back the optimism of mid-twentieth century capitalism. Legendary Canadian cartoonist Seth lovingly shows the rituals, hopes, and delusions of a middle-class that has long ceased to exist in North America—garrulous men in wool suits extolling the virtues of the wares to taciturn shopkeepers with an eye on the door. Much like the myth of an ever-growing economy, the Clyde Fans family unit is a fraud—the patriarch has abandoned the business to mismatched sons, one who strives to keep the business afloat and the other who retreats into the arms of the remaining parent.

The story’s events span over a lifetime—or more accurately, two lives’ time—as the narrative cuts across years into intimate and revealing moments in the lives of two brothers, Abe and Simon Matchcard, who inherited an electric fan company from their father, Clyde, in mid- 20th century Canada. In keeping with much of Seth’s work, everything in this graphic novel reeks of the dull pain and sharp pleasures of nostalgia, from the inevitable decline of an electric fan company in an age of air conditioning to the rending dementia-haunted last years of Simon and Abe’s mother’s life. Seth’s oeuvre has aestheticized nostalgia, in its fetishistic wonders, in its very human grief of loss, in its evocation of memory, as few artists have, particularly for the white North American middle-class existence that was intertwined with the commercial culture of late capitalism. So intertwined that nostalgia and memory are hard to disentangle.

Seth positions his protagonists Abe and Simon, two very opposite brothers, orbiting around objects of this nostalgia/regret, objects like the household trinkets sitting around their mother’s room for decades, or the Ontario-area city streets where Abe (and at one time, lamentably, Simon) worked the store-to-store salesman’s route, or indeed the Clyde Fans business itself. Abe is the more enterprising but Willy Loman-esque, blustering brother with the balding combover and braggadocio mustache. After their father abandons his wife and the electric fan company to his sons, Abe has shouldered most of the business interests, surviving the company’s small rise and inevitable descent in an air-conditioned modernity. The first hundred pages of the book center on old Abe waxing about a yesteryear salesmanship gospel while he shuffles around his apartment and the dusty, ill-lit storage corners of the closed-down Clyde Fans storefront. This extended opening we spend with Abe, meandering through home and office and streets, is a benchmark in comics characterization. I remember reading this monologue in “Clyde Fans Book One” fifteen years ago and being spellbound by this rambling old man talking about selling fans. He was so utterly human in ways I saw so rarely in comics.

Though Seth draws Abe’s eyes as worn, worried, and weathered slits, Abe’s soliloquizing words carry that irrepressible flicker of the salesman’s optimism. Of course, that optimism is as tragically tinged and morally voided as Arthur’s Miller’s desperate Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman.

Especially as we see the darker underbelly of antipathy that comes with those capitalist aspirations, most apparent in the emotional violence Abe inflicts on his brother Simon. As Abe introduces his brother in his monologue, we are set up for the somewhat pathetic and obsessive character we will come to meet, who comes to sit at the center of Seth’s picture novel. But Simon’s faded light in the distance revolves into our empathic point of view character, as we pace nervously through a humiliating 1957 sales trip with him, as we inhabit the ambiguities of his experience in 1966 caregiving for his aging mother in their aging home, and as we ponder the curiosities of his collector’s obsession with 1920s novelty postcards and his strange and familiar compulsions. As it turns out, both brothers grasp to seize a disappearing past, circling in bitterness and sometimes poignant love.

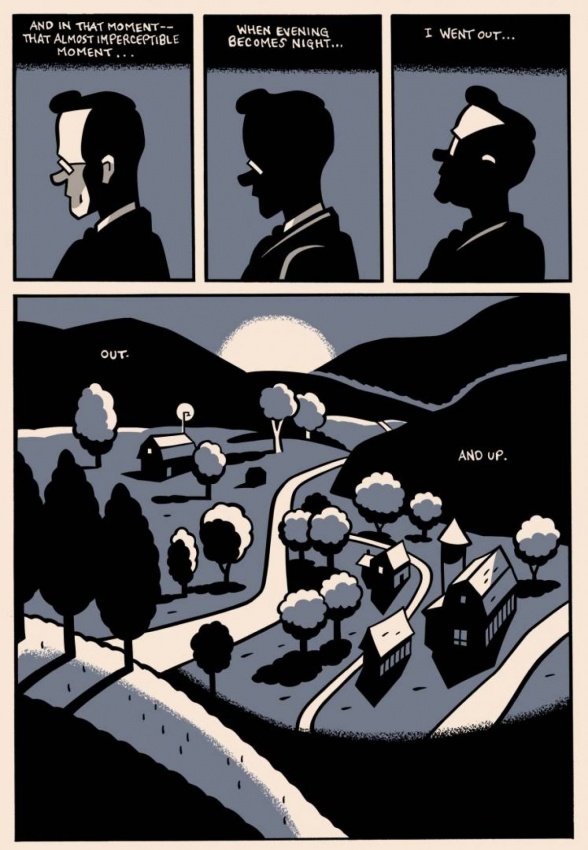

Continued belowThat poignant tinge also comes with a certain restless energy, the kind familiar to those of us who have spent time with old folks. The book’s two brothers are almost always seen walking. And we as readers, taken along real/fictional Canadian byways by a restless narrative eye, are also carried along by a narrative machinery of perpetual, drifting motion. We follow a younger Abe on philanderer’s hunts. We jump back in time and follow Simon, plagued with social anxieties, unfit for the salesman’s life, on his mental flights of escape. And along the way, like our restless 20th century lives of sorting through the millions of material artifacts of our commodified existence, Seth gives us sequences that feel like walking window shopping, catalogue flipping, or roaming ghost-like above city streets. Over the course of the book, we find ourselves passengers in Simon Matchcard’s imagination roving in quest for “a frozen life” or “a sort of enchanted place” for long stretches.

Paradoxically, Seth also captures the feeling that things of the past are bottled up, boxed in, collected and contained, placed onto shelves and organized for exhibition or cataloguing. But just like the floating value of a name brand in free market capitalism, just like our tenuous grips on memories and attachments to memorabilia, even like the ultimate insecurity of our nostalgias of home, nothing stays.

If you’re familiar with Seth’s work, one fascination of the book is a subtle shift in his drawing style over the twenty-five years of the book’s creation that to me is reminiscent of one of his influences, Charles Schulz, towards a more iconic sureness of line and impressionistic rendering and framing. The first two sequences, old Abe’s meandering yarn and young Simon’s failed sales trip, feature Seth’s art as I remember it from “It’s a Good Life if You Don’t Weaken,” attractively styled but still beholden to the anxious linework that echoes the one-panel magazine cartoon and illustration style that casts a large shadow over that book. The latter segments of “Clyde Fans” swing towards the thick-lined icons and art deco-y negative space that Seth seemed to use more freely as storytelling in “Wimbledon Green” and elsewhere. Along with those art shifts, the narrative style also seems to age with Seth, as poetic longing and rhythmic rumination marks the movement from an Abe-framed view of the world to a Simon-sounding reverie.

“Clyde Fans” deserves this beautiful printing by Drawn + Quarterly, a smart hardback with a window in the front cover revealing the book’s title in unmistakably Seth-ian font. It’s a production design worthy of the book’s modest, fascinating beginnings: Seth (whose real name, Gregory Gallant, always sounds to me like IT should be a pen name) would often walk past an actual “Clyde Fans” store selling electric fans in his native Canada, with a picture seen through the window of the brothers who owned the business.

What the complete “Clyde Fans” gives us is the prospect of the narrative Seth has always meant to tell, through the portions we saw in drips and drabs in Seth’s “Palookaville,” but revised substantially and made into the whole that is closer to Seth’s intent. At least, his intent circa 2019. It seems important to mark the date of this publication, since the book itself takes such pains to mark the dates, the years, when we are encountering Abe or Simon at particular points in their lives. The years matter because of what point the brothers are, as we jump around in their lives. They also matter because we see Ontario area urban life at certain stages of fading desperation or the boom and renewal in which Clyde Fans struggles to remain relevant. And we also mark the years, as we jump to Simon and Abe, young and old, to piece together where Seth seems to be taking us after all these years through these disparate vignettes.

To me, it’s an open question whether Seth’s theme of restless longing, that obsessive itch of nostalgia and its lifetime fallout, means the same thing to a comics readership of 2019 as it did to one of 1997. Seth seems to know this, too. One small, revealing element of “Clyde Fans” that Seth has revised to make clearer, as he pointed out in a Comics Journal interview, is the haunting Black caricature toy once acceptable— popular, even— as a commercial novelty item, horrid artifact of the overtly racist common sense of the past. In a very Northern version of the ghosts in Faulkner’s Southern Gothic, the toy, and a pickaninny novelty item Simon encounters elsewhere in the story, seems to continue to speak to Simon as an almost devilish conscience that all is not well, that deep corruption lies beneath even our fondest, rose-colored memories. Nostalgia is not only chasing to capture what we can’t return to, but also what we shouldn’t.

In my mind, that notion seems to run parallel to how that particular kind of nostalgia sat right at the heart of a large swath of the graphic novel readership in the late nineties, which Seth evoked so powerfully. But a different form of nostalgia, with its own peculiar dangers and fascinations, its own commodification and commercialization, has overtaken the majority of comicdom. “Clyde Fans” will no doubt be canonized by many comics collectors and critical cognoscenti, but in a time when rightfully, though some may say tragically, those canons are crumbling into irrelevance. Yet maybe for exactly for that perspective on the other side of irrelevance, those of us GenX and Millennial consumers stuffing our box offices and comics charts with rehashes of our own collective cultural memories should take heed. This brick of a paean to what fades is actually about human experience, and we all fade that way too.