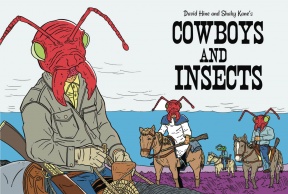

David Hine and Shaky Kane reunite to tell a tale of morality, touching on many facets of American life. This should be nothing new to reader’s of the pair’s work, as their last collaboration, “The Bulletproof Coffin,” touched on, amongst other things, the ethical treatment of artists in the comics industry. In “Cowboys and Insects,” the scope becomes much larger, and in some ways, far more direct. This is a one-shot comic that’s packed tight with allegory and metaphor, to say the least. Mild spoilers ahead.

Written by David Hine

Illustrated by Shaky Kane

Kane and Hine follow up their cult hit The Bulletproof Coffin with this paranoid tale of troubled romance in an alternative 1950s, where the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests have had an unexpected effect on North America’s insects. This one-shot is an epic story of Big Bugs and the men who wrangle them. A Floating World production.

OK, first thing’s first, a disclaimer: I’m vegan. Have been for a while now, and anyone who knows me can tell you that it is not for health reasons. My decision to keep this sort of diet came about purely for ethical reasons, which stem from my views on eating the flesh of other living things. I don’t bring it up often, as it’s my own belief and would rather avoid being labeled as one of those ‘preachy’ vegans. Despite my thinking, people still get bent out of shape when they find out I don’t eat meat and assume that I’m going to drop a PETA pamphlet on them or something. So why bring this up at the top of a comic book review? Well, because Hine and Kane are speaking directly to this.

The world of “Cowboys and Insects” is one where cattle farming has gone the way of the Dodo, replaced by a system of raising and exploiting gigantic insects. It sounds like an absurd idea, but nicely lends itself to one of the book’s central ideas. By removing cattle (or fish or poultry) readers are placed in a world where their own actions aren’t directly being called into question. The reason I feel that some people act offended by my veganism is because they assume that my decisions indicate that I am judging their own. It’s a simple right/wrong scenario, and no one like to be accused of being wrong, especially when it comes to something as intimate as what we put into our bodies. So with bugs instead of cows, Hine and Kane are able to freely examine rodeos, factory farming, education and social normality without dividing the readership. Plus, it gives Kane an especially fantastic world to draw, which is surely a specialty of his.

What Shaky Kane does on these pages is quite interesting. We’ve covered the replacing of farm animals with insects, but this is an idea that is driven home in the art. It’s not just that Bugs Are Food, but that bugs are everywhere. It’s easy to lose sight of it, but we are exposed to a massive amount of food-animal iconography. Cartoon versions of livestock are placed on packaging and billboards in order to sell products and ideas, so seeing the familiar swapped out with the bug equivalent serves as a shock to readers. It communicates how influential marketing is, and how fluid messaging can be when necessary. There are no images of chickens because no one has to sell them and, by extension, there’s no need to normalize their consumption. This is touched on briefly, as we find out why in a world of bugs, people are still referred to as ‘cowboys.’

Throughout the issue, Kane does everything he can to overstate the presence of insects in human life. Every one of his panels run dense with signifiers of what is to be considered normal, rendered in his signature line style. His bold and open approach to art adds an element of surrealness to the story, which makes the reader feel the exaggeration in the narrative even more acutely. His character work heightens this, as every person we see has subtly abnormal proportions and seemingly deep creases on their faces. It’s almost as if each of his characters are built like ventriloquist dummies, with arms and legs that are just a little too short. His acting feels odd too. Kane conveys motion as if characters are posing for pictures, rather than making real movements, almost as if he’s directing them instead of capturing moments in time. “Raise the knife a little higher… now look into the camera.. good, hold that.” The final, and probably most present aspect of Kane’s work is the color. His palette choices are bold, hyper-saturated, and flat. It’s like he’s taken a fluorescent approach to the cel painting of ’60s animation.

Continued belowWhat’s fascinating about Kane is how well he makes all of this work. Most of the time when you describe someone’s art as posed and flat, it’s intended to be a negative. Nothing could be further from the truth. Kane uses these elements to create pure magic on the page. His style is one of my favorites, and that comes from his idiosyncrasies. He’s clearly in the Geof Darrow/Seth Fisher school of comic art, but with a pop art sensibility.

While Kane put in a lot of effort to communicate what this world is like, David Hine does well to populate it. Almost everyone in this comic are happy and comfortable with their lives as they are. They live the lives of laborers in Bug Town, Colorado, where Big Bug Products is the largest employer. We’re shown a little of what the company’s outposts like Double B Ranch and the Big Bug Plant are like, as workers raise all manner of insects and machine them into a line of meats and by-products. Families are able to live comfortable lives because of what Big Bug produces, so it’s easy to see how people would react harshly when someone decides to buck the norm.

In a town like this, with beetle rodeos and plentiful bug meat, how would it be perceived is one family chose not to participate? To be vegetarian? Well, if Hine is writing the story, not very well for anyone. When a family in Bug Town, vegetarians mind you, are caught bestowing kindness upon an insectum erectum all hell breaks loose. What is an insectum erectum, you might ask? Well, it’s a bug that walks upright and is humanoid in its shape. For all intents and purposes: a man with a bug head. His fate is to be dissected by school children. To my mind, this is Hine playing in the arena of animal testing, specifically on monkeys. These are animals that we can see ourselves in, as the shapes and motions are so similar to our own. It’s about as close to a line between human and animal as one could imagine, yet people have no qualm exploiting these creatures. This is the ground that Hine and Kane stand on to make the biggest point of this comic.

What will people do to protect their own way of life? How far is too far in the pursuit of normalcy? It’s here that Hine rips back the curtain to show us the big picture, and despite Kane drawing it, it’s not pretty. Hine implies that this is how an organization like the KKK can spring into prominence, and we see some horrendous acts being perpetrated by masked characters. What happens at the climax of this story is so clear, so real-world that I hesitate to call it allegorical. Yes, it’s bug related, but it’s also a very real interpretation of a mid-century United States, a time and place where these sorts of actions collided headlong with post-war modernism. There’s a sickening dissonance happening, as we’re privy to one character’s internal narration. He is not a person who would choose to do this on his own, but he’s also someone who would go along to get along. A passive participant who may not agree with what is around him, but stands to benefit from it, thus ensuring complacency. We all see what happens to those who run counter to what is considered normal, so just shut up and enjoy the spoils of privilege. While the insectum erectum steps onto the stage as a symbol for the treatment of animals, it ends the story as something much larger, becoming a fill in for race, religion, sexuality, or any other qualifier that the power structure crushes under boot in order to make an example.

When I first saw this comic solicited I knew I’d pick it up. These creators, especially together, have a winning track record, so it was an easy decision. That said, I had no clue what was awaiting me. The fact that such a rich social commentary was waiting behind a seemingly absurd concept was, to put it lightly, surprising. The first half of the issue seemed to be all about the decision to not eat animals, which I found surprising and relatable. That was just Hine’s set up, though, as the line of thought initiated early in the issue was quickly built upon to provide a more thorough worldview.

Final Verdict: 9.0 – An immensely powerful story that utilizes the full potential of the medium. In less than two dozen pages, Hine and Kane leveraged symbol and metaphor in order to poignantly make a point about the folly of homogeny. What would appear to be cartoons and silly at first blush, quickly uncoils a rich narrative that is simply not to be missed.