Sometimes, it can be very easy to see a career trajectory in front of you. Certain creators just jump out at you – after seeing Scott Snyder’s work in “Detective Comics,” it was easy to dream on his talent and see big stories in his future. But other creators take a more circuitous route to their eventual career.

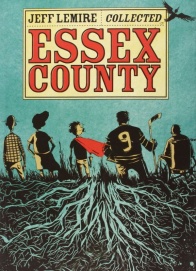

That’s a murky description for how Jeff Lemire’s career has taken him to places totally unexpected. The “Essex County” books represent such a singular type of story, that it would be nearly impossible to picture him writing “Justice League” stories as being one of the architects of what Valiant is doing in 2015. And yet, that’s where he is; but it all started with a kid in a cape, trying to understand his life and his uncle, with varying degrees of success.

Written and Illustrated by Jeff Lemire

Where does a young boy turn when his whole world suddenly disappears? What could change two brothers from an unstoppable team into a pair of bitterly estranged loners? How does the work of one middle-aged nurse reveal the scars of an entire community, and can anything heal the wounds caused by a century of deception?

Set in an imaginary version of Jeff Lemire’s hometown, ESSEX COUNTY is an intimate study of an eccentric farming community, and a tender meditation on family, memory, grief, secrets, and reconciliation. With the lush, expressive inking of a cartoonist at the height of his powers, Lemire draws us in and sets us free.

I’m someone who came to comics through superheroes at a very young age, and so if you woke me up in the middle of the night and asked me what comics are, I’d probably still say something like ‘wish fulfillment through over the top characters.’ But in my heart of hearts, I know it is more important that comics are being made like “Essex County” than if there’s ever another Spider-Man or Superman story ever published. Sequential art can tell stories in a totally different way than any other medium, and it especially does wonders for nostalgia and longing – and this story is chock full of both.

The first book, “Tales From the Farm,” is all about young Lester, a boy orphaned by the death of his mother, who is living with his Uncle Kenny on a farm. Les and Ken try to understand each other, but Ken is a farmer, a serious man who likes his hockey and takes his work seriously. Les likes hockey, too, but he also has an active imagination and loves comic books, and is a kid – a kid that Ken didn’t anticipate raising.

Lemire draws Lester with such inherent sadness and pain behind his Robin mask, and he shows Ken’s labors all of him – both his physical and emotional ones. Ken is a simple man – we don’t really know much about his ambitions, or his dreams, but we know a lot about his reality. He has to work hard to put food on the table, and he does so without complaining. He also raises Lester without complaining, although not without a fair amount of regret, certainly.

This entire chapter is spare with its dialogue, but rich with its emotions. The stark black and white of the book helps illustrate the desolate Canadian countryside where Ken’s farm is situated. Les and Ken are both sad, both disappointed with how their lives turned out, and both realize that there is nothing they can do about it. The way that Lemire conveys this is nothing shy of brilliant. He uses the eyes of both characters as the only telltale signs to how they’re really feeling. Lester’s eyes, outside of his mask, are small dots that betray nothing about how he is feeling, but when he has the mask on, he’s wide eyed. The masks allow him to see the world as he wants to see it; when it is off, everything seems small and sad. Kenny’s eyes seem perpetually filled, not necessarily with tears, but with exhaustion. At times, he does seem on the verge of tears, but we never see him break down. He’s trying to be the man in Lester’s life, and in his mind, that means he has to be overly tough.

Continued belowThis chapter also introduces us to Jimmy LaBeuf, former hockey player and current proprietor of the gas station in town. Jimmy plays a role in all three stories in the book, and in many ways is the heart of the story: Jimmy had great dreams, and those dreams got dashed, forcing him to settle for a life that is far less dynamic than he had hoped. The best scene in this chapter is when Jimmy is reading the comic that Lester made. Jimmy’s reaction is so sincere – he loves the comic, and as the story goes on, we begin to understand why, for a number of reasons. Jimmy and Lester make for a great visual pair, as Lester is a beanpole without an ounce of muscle on him, whereas Jimmy is a hulking brute of a man.

That same body type dynamic is on display in “Ghost Stories,” the second book in the trilogy. This story involves Lou and Vince LaBeuf, hockey playing brothers from the farmlands who come to Toronto to play hockey. In many ways, this is the most typical of the three stories – it is a story of betrayal and family and love and responsibility. Its predictability doesn’t really hamper the story, and the device for telling the story – a demented, ancient Lou reliving his youth while at the end of his life – makes up for any lack of surprises found within.

Lou is the narrator, the less talented, and less physically imposing of the brothers LaBeuf; and yet, he is the catalyst for everything that happens in the story. Lou invites Vince to come to Toronto to play hockey, Lou acts on his carnal impulses, Lou’s silence and distance strains every relationship in the story – hell, even Lou’s lingering guilt and familial responsibilities eventually bring the story to its conclusion. This story plays around with the idea of what a family means, and Lou represents both the best and worst parts of family.

This story is also the most hockey-centric and, therefore, the most Canadian of all the stories. As a casual hockey fan, I can’t comment too much on the hockey content, but sport is always a great device for storytelling, and hockey here represents Lou’s innermost dreams. He is happiest when playing hockey, and happier still when he can do it alongside his brother. When Vince, eventually, leaves hockey behind, that is when Lou leaves his brother behind as well.

This chapter is told mainly through flashbacks, and Lemire’s art style for each section is distinct. The past has a heavy line that shows strength and vitality, whereas present day is thinner and less robust. Lou, throughout the years, bears almost no resemblance to his younger self outside of his nose and eyes (again with the eyes), and Lemire does a nice job of aging him, and all the characters, in realistic ways, not just making them get a little fatter, balder, and greyer, as so many people would.

In this story, we also meet Lou’s nurse, Anne Queenville, who becomes the co-lead of the third story, “The Country Nurse.” Mrs. Q, as Jimmy calls her, is a put-upon nurse for the elderly, and she tries her best, but rarely succeeds in a way that satisfies her. She’s a hard worker, she’s a widow, and she’s the mother of a lazy son. She’s also the granddaughter of Sister Margaret Byrne, who shares the story with her. Margaret is a Catholic nun in a country orphanage, and her story of shepherding children across the cold expanse fits nicely into Anne’s attempt to shepherd the elderly across the tough terrain of old age.

Both of the ladies can come off as tough and hard-nosed, but they both use that to shield themselves from the harsh realities that life has presented them. This book has a character in Anne that loves to talk, but she has no one to talk to, making the book feel even more claustrophobic than “Tales from the Farm,” which featured two characters who didn’t really want to talk. She has the most robust conversations with her dead husband who, obviously, can’t respond. Anne rarely ever shares a panel with anyone else, and when she does, they are usually unable, or unwilling the respond.

These three stories, as well as the ephemera that is also collected in this edition, paint a world that is incredibly specific and detailed, even if, like me, you know nothing of the actual Essex County, Ontario. Lemire’s portraits of people are honest, and sad, and are full of broken dreams. All of these characters are living lives different than what they expected, and yet none of them really give up. And that is why a comic like this is so important – it is far more aspirational than a Batman story, even though no one in this book could do what Bruce Wayne does. But all of us can pick ourselves up, shake off the dust of disappointment, and try to live the best lives we can.

When I was a kid, I wanted nothing more than to be able to do what Superman does. Now, as a father, I would much rather have the work ethic of Uncle Kenny, or the caring love of Vince LeBeuf, or the kind heart of Anne Queenville. And so, while Lemire has been able to take the storytelling skills present here and bring them to “Justice League United” and “All-New Hawkeye,” I don’t know if he’ll ever tell a more heroic story than the small victories for the very real heroes of “Essex County.”