Seizures are terrifying things. While I am not an epileptic, I had a number of what are called febrile seizures as a small child, a trait that I sadly passed on to my daughter. When she was 11 months old, she had a 90 minute ‘complex’ febrile seizure, which is practically unheard of; at one point, the doctor came up to me in the ER and said “I have no idea why she is still seizing.” It was one of the worst moments of my life, and a harrowing experience that I will never forget.

Now, imagine that happening to you, but you’re alone. And there is a hallucinatory aspect of it. And it happens with some frequency.

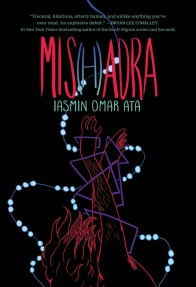

That’s the story told in “Mis(h)adra,” a story based off the reality of creator Iasmin Omar Ata, and it makes for a truly fascinating and moving story.

Note: This is a review of the Gallery 13 hardover edition of the book, not the serialized, self-published comics, in case any difference appears between the two.

Written, illustrated, colored, and lettered by Iasmin Omar AtaCover by Iasmin Omar AtaAn Arab-American college student struggles to live with epilepsy in this starkly colored and deeply-cutting graphic novel.

Isaac wants nothing more than to be a functional college student—but managing his epilepsy is an exhausting battle to survive. He attempts to maintain a balancing act between his seizure triggers and his day-to-day schedule, but he finds that nothing—not even his medication—seems to work. The doctors won’t listen, the schoolwork keeps piling up, his family is in denial about his condition, and his social life falls apart as he feels more and more isolated by his illness. Even with an unexpected new friend by his side, so much is up against him that Isaac is starting to think his epilepsy might be unbeatable.

Based on the author’s own experiences as an epileptic, Mis(h)adra is a boldly visual depiction of the daily struggles of living with a misunderstood condition in today’s hectic and uninformed world.

Comics allow autobiographical storytellers a real gift of allowing them to present their experiences with visual filters not afforded prose writers. There is something magical in creating a mental image based off text you’ve read, but it is a different story altogether to share the exact visual composition intended by the creator. Ata’s book is so effective because he is able to present the reader with his interpretation of his seizures, which is a more personal and intimate action than even watching him seize in the same room.

Ata crafts the seizures, visually, as the converse of the rest of the book. While most of the pages have bright fluorescent tones against a white background, the seizures go negative, with black being the primary background color, and the colors popping off like the side of Shea Stadium.

Ata uses images of daggers as the manifestations of the pain and confusion of the seizures, and we see them, at times, sneaking up on him and taking him by surprise, echoing the feeling of a sudden onset of a seizure. One of the things that Ata does most successfully in the book is to tackle that issue of surprise. Isaac, the stand in for Ata, is trying to be a student, a roommate, and a friend, but all of those pursuits sometimes get thrown entirely off track by his epilepsy.

The scenes of his actual seizures are the most effective of the book, as they thrust us directly into Isaac’s shoes. At times in the book, Isaac can be aloof or unresponsive, both to those in his life and to the reader, but in these scenes, he is present and aware of every second of time. In a weird way, these scenes are far easier to understand and relate to than almost any other part of Isaac’s life. There is an order to the chaos of the seizure that isn’t present in how he deals with the rest of his life.

And in a way, the seizures are presented as a thing of beauty. Due to the black backdrop, the colors dance off the page, creating surrealistic imagery that registers as beautiful before dangerous. Even when you know better, by the back end of the book, the images are so dramatic that you’re drawn in before being repulsed.

Continued below

Ata’s characters are somewhat reminiscent of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s work, where there are touches of manga, western comics, underground comix, and videogames all present. Maybe I’m reading the videogames in there a bit, but the book feels very episodic to me, not unlike an old side-scroller like Super Mario Bros, where different levels would be differentiated by color schemes and music. The character work is all about the hyper expressive faces and body language, conveying far more than the text itself.

There are a number of elements throughout the help manifest Isaac’s alienation onto the page, from the shock of blonde hair that instantly makes him stand out, or the ignored texts and calls that, at times, appear to be his only tether to the outside world. Even when he makes friends, like Jo, who acts as his guardian angel at several moments, he pushes them away instead of letting them truly be present to him. Jo’s perseverance is almost Atlas-ian, listening to Isaac when no one else will, advocating for him, and forgiving him.

The book uses jumps in time, health, and situation quite liberally, to help understand just how chaotic Isaac’s life is. In fact, the chaos, both from the jumps and the surrealistic images of the actual seizures, make for a purposely confusing read, and one that allows things like the loss of an eye to be questioned. Is this a hallucination, or did he really lose an eye? (Spoiler alert – the eye is gone)

The solicitation for the book, as well as a lot of the press surrounding it, mention that Isaac is of Arabic descent, a factor that doesn’t really play at all into the narrative. Perhaps it can be argued that Isaac’s father’s apprehension of accepting his son’s diagnosis is a cultural aspect, but I didn’t read it that way. I kept waiting for his heritage to factor in more, and that shoe never dropped. I’m not complaining, necessarily; it was just odd for what felt like a key selling point to be so thinly featured. Perhaps Ata’s personal heritage is so important to him that he feels it is a bigger part of the story than it appears to the reader. Or maybe I just missed the subtext.

The weakest part of the book was the ending, which felt rushed. If Isaac hit rock bottom, it isn’t presented as clearly as it, perhaps, should have been. Isaac gets kicked down so many times until, one day, he chooses to get back up. There isn’t a big moment of revelation, he’s just in a better place all of a sudden. Again, perhaps that is my reading of this, that there needed to be more of a struggle to the resolution. But for a book that kept me rapt and invested in every panel, it seemed to resolve jut a bit too easily.

Overall, the book is a fascinating look at a misunderstood disease that is both terrifying and mysterious. It is all the more harrowing when you remember that Ata went through something similar with his own epilepsy. The book does its best to make you understand his condition, using fewer words than you may expect, but delivering something truly memorable that will keep gnawing at you long past when you put it down.