Farel Dalrymple has been an artist lurking on the fringe of comics for a while now. He was introduced to the mainstream with an absurdist reinvention of Marvel’s “Omega The Unknown” and has since worked on his own titles and projects like “The Wrenchies” with his signature hyper-detailed penciling. Now, he’s releasing a mini-series that looks to capture his high energy and emotion and distill it into a linear story. Does his work translate well?

Written, Illustrated, Colored and Lettered by Farel Dalrymple

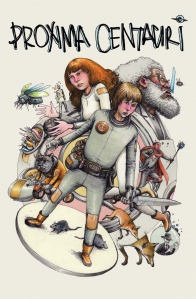

“PROXIMA CENTAURI,” Part One 4.243 light-years from Earth, the teenage wizard adventurer Sherwood Breadcoat is stuck in the confounding spectral zone on the manufactured dimensional sphere, Proxima Centauri, looking for escape and a way back to his brother while dealing with his confusing emotions, alien creatures, and all sorts of unknown, fantastic dangers. In this issue The Scientist H. Duke sends Sherwood on a salvage mission and gives counsel to the troubled boy in his charge. PROXIMA CENTAURI will be six issues of PSYCHEDELIC SCIENCE FANTASY ACTION COMIC BOOK DRAMA starring Sherwood Breadcoat, “The Scientist” Duke Herzog, Dr. EXT the Time Traveler, the ghost M. Parasol, Shakey the Space Wizard, and Dhog Dahog.

Upon first read, or even upon cracking this book open, you will realize this is a heady text. Dalrymple has a lot of big symbolism and metaphor going on for the teenage experience, but it’s all focalized with how our protagonist Sherwood Breadcoat views and interacts with the world around him. We’re introduced to the character through a small prologue, of sorts, as his internal narration informs us that his goal is searching for his brother. Farel keeps this as the most concrete detail through the story, so as to humanize the characters but keep everything else ethereal and psychedelic. But what’s also interesting is the way that Sherwood interacts with everyone is with the hormonal impatience of a typical teenager. It makes him feel like a deeper character than the rest of the cast, as he doesn’t always agree with what is going on and often tries to buck the status quo. He asks questions like “How old do you think I’d have to get for Parasol to be my girlfriend” to remind people of his age. But then he also asks more relevant and aware questions, reflecting the teens of our current era, saying “What happened to my sense of wonder? Meh. Nothing’s impressive anymore”. It gives the comic an awareness above being a simple teenager coming-of-age type tale.

Dalrymple uses setting very loosely and with fluidity in this book, with everything seeming to tie back to the piece of narration “You’re a teenager. And you believe the whole world is only what’s happening to you”. Everything that happens seems to be constantly morphing due to Sherwood’s impatience and overall disinterest with the world around him. The nature of the environment Sherwood and his friends are in, Proxima Centauri itself, is ‘a manufactured dimensional sphere,’ and fits this idea of an environment informed by a teenager’s thoughts well. From the start of the main story, Sherwood appears to be in a sparse surrounding, with everything becoming more populated as he starts to focus and become more interested in what he’s doing. Similarly, the characters that we see on the page at any given time are always changing, with some being present just to interact with Sherwood, and some, like the Space Wizard and Dr. Ext, the time traveler, seem to have an agenda of their own. It’s an approach to storytelling that feels in tune with the protagonist’s pseudo-ADHD attitude, but might feel scattered for some, as there’s is rarely a concrete place mentioned or seen for readers to connect with.

Pacing is on point for most of the time here, with Dalrymple delivering a tight, rock-solid script that keeps rolling the action and headiness forward till the end. As soon as we open onto the main story, we’re placed right into the thick of things, watching Sherwood rocket through mid-air to reach a ‘weird spot’ destination. It’s almost like a second act start, with the planning and deciphering of this event occurring prior to this to ensure that the main story is fast and consistent. Sherwood, Smiley and Duke Herzog all go page to page exploring their morphing environments, taking just a panel or so to let the reader soak in the strangeness before moving off before we’re completely settled. It’s a great way to ensure that nothing ever lags or feels boring, but can be disorienting to casual readers. My only problems with pacing are with the bookends of this package. The prologue feels a lot more decompressed than the main story, and as the opening of the book might feel slow to people flicking through. Similarly, the ending of the main tale happens quite abruptly, with the ‘angry bully threat’ only speaking a full sentence in the last page to give context that he is out to get Sherwood. It does clarify the last sequence when looking back in hindsight, but it feels fast forwarded significantly compared to the rest of the book.

Continued belowThe soft, detailed penciling that Dalrymple is synonymous with translates well into the psychedelic world of “Proxima Centauri”. This style is present throughout the book but seems changes to fit the scene. The pencils tighten up in sequences of quick action and become slower and denser to become immersive in emotive panels. Sequences like Sherwood sliding down a curved surface and falling through the air to a platform below have a loose and quickly-inked feel to give a sense of speed. In contrast, the scene of Sherwood pushing through the barrier into another dimension shows a detailed look of determination and more thorough shading and penciling. Outside of penciling, however, we can see by looking at this book as a whole that the use of negative space is key to giving this world an expansive and infinite feel. The first double page of Sherwood and Space Wizard feels huge not because of the detailing in it, but because detailing is localized in one spot, and sparse throughout the rest of the environment to convey the enormity of the scene. Dalrymple has a style that not only conveys pacing and emotions well but still retains the expansiveness of a good sci-fi too.

There’s a level of control in Dalrymple’s sequential action and emotion that isn’t seen in a lot of other comics. Open up to any page, and you won’t see a character looking stiff or static anywhere. The elegant strokes used means that Dalrymple’s work has a lot of fluidity, making the sequential work look carefree and breezy. Every figure looks appropriately like they are reaching out in low gravity, with no moves feeling forced or urgent. The two-page sequence of Sherwood reaching through the dimensional barrier into another world is fast-paced and quick to occur, yet Sherwood’s body language never looks tense or urgent – rather, he seems to be languidly pushing through a soft-looking barrier due to the way his hands react to the surface they are pushing against. Visual emotion is accentuated well in this comic too but feels at its most dynamic when conveyed through Sherwood. Considering that he almost works as a point-of-view character for the audience, this makes sense. We see him bored when asking how many earth-years he’s been adventuring, we see him rash and confused when he realizes his feelings for Parasol aren’t reciprocated, and angry when he falls in error. Yet other characters are relegated to feeling more one-note – Duke Herzog has a constantly ajar mouth, and Parasol is a constant sheet of placidity. It makes them feel less real on a visual level, especially compared to Sherwood.

Colors here are appropriately sparse, dedicating most of the palette to whites and beige to accentuate negative space and focalize smaller bursts of vibrancy. What’s interesting is the texturing of the color itself. Dalrymple has a soft shading style that looks a lot like pencil coloring, if not actually being pencil coloring. It compliments the detail in the characters drawing well, giving a very children’s picture book sense of wonder to the whole text. I also love that a pastel palette is used even in scenes of alarm. When we see a bullet emerging from Duke Herzog’s head, the background changes from a beige to a soft pink, highlighting the psychedelic nature of the text.

“Proxima Centauri” may not be for everyone. It’s ethereal and highly metaphoric, with a constantly shifting style that will catch out anyone with a short attention span. However, put in the effort and time that this comic deserves, and it will open up to you. Dalrymple’s story focalized through the thought process of a moody teen is wonderfully original, and his unique art style compliments it well. This is a book for those seeking more in their conventional sci-fi.

Final Score: 8.3 – Like it’s teenage protagonist, “Proxima Centauri” #1 is fickle and moody, but endlessly rewarding to anyone willing to spend the time to listen to it.