In fiction there’s a rich tradition of celebrating a medium of storytelling by creating a story about it. It’s something you can see across the board in most popular storytelling mediums, whether in film with things like Barton Fink or Singin’ in the Rain or in fiction with “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller” or even “Fahrenheit 451.” Sometimes it’s biting, sometimes it’s very loving, but more often than not we seem to love to tell stories about stories and the creation of stories.

It’s also an idea heavily prevalent in many comics, to say the least. Most people who turn to creating comics begin as fans, so that there’s an overlap feels incredibly natural. However, unlike with other mediums, comics seem to like to play with meta-fiction more than most; heck, it seems to be the basis of most Grant Morrison comics, as the power of storytelling is something that deeply moves and affects us. Remember “Final Crisis?”

And today, this idea of fiction about fiction, the love of creating and a celebration of a medium of storytelling brings us to “The Wrenchies,” the new graphic novel written and illustrated by Farel Dalrymple, recently released from First Second.

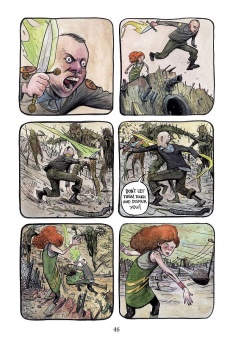

Explaining what “The Wrenchies” is about isn’t entirely easy. It’s the story of Sherwood and Orson, two young boys who journey into a cave. It’s also the story of Hollis, a young boy with a crisis of faith, a ghost pal and a love of comics. But as the cover would suggest, “The Wrenchies” is also about a post-apocalyptic future wasteland, where dark figures in suits hunt down gangs of magical and violent children. We focus in on The Wrenchies, a particular group who is on the run from the shadowmen and just happen to get involved with an epic quest as barriers between reality and fiction are blurred and danger escalates tenfold.

But talking about this aspect of “The Wrenchies” only really scratches the surface. While there’s a high adventure and a great concept to it, “The Wrenchies” is decidedly much more than either; it’s a machine with gears that don’t all fit, yet it chugs along never the less. What it produces at the end, though, is an interesting and slightly ambiguous book — and what’s ultimately fascinating about “The Wrenchies” is how it at times feels like it shouldn’t work, and yet it all absolutely does.

With the help of Farel Dalrymple, we’re going to explore just why that is and how it works.

I’ll cut to the chase a bit and note that “The Wrenchies” is one of my favorite things I’ve read this year. Highly imaginative and wonderfully fluid, “The Wrenchies” is about many things: post-apocalyptic adventures, epic quests, fantasy and science-fiction, and growing up misunderstood in a world that doesn’t seem to have a place for you. But for the most part, it’s a book about how damn great and powerful comic books are.

For Dalrymple, it seems like there was never much of a choice in what else he should spend his time with. “Comics are just what I wanted to do from early on in my childhood,” Dalrymple related to me in an interview about the book. “I was fascinated by the medium because I had friends who were into them, and the comic rack at any grocery store was a spot I would spend a lot of time at. My mom encouraged me to draw and I was making my comics all through my life without thinking about doing much else.”

“When I was in art school I thought I might be an illustrator or fine artist but I still mostly just made comics. At this point it just feels like an addiction or a crazy obsession that I am trying to build a career around.”

And this quality has translated to his work, both here and elsewhere. Dalrymple’s work should certainly be recognizable to fans at this point, as his comics have led to some rather notable stand-outs in storytelling, such as with “Omega the Unknown” at Marvel or “It Will All Hurt” from Study Group Comics, which is the closest point of comparison to “The Wrenchies.”

Continued belowIn fact, one of the most interesting aspects of “The Wrenchies” that actually colors the book in a different way is that it was released as a graphic novel and not serialized fiction — at least, for Dalrymple. “This is the biggest work I have done to date,” Dalrymple said. “To have it all released at once instead of being serialized like all of my previous work was an interesting but somewhat isolating experience. Working in solitude for so long was probably the biggest challenge. I would show pages to anyone that showed a slight interest in them. Most people wanted to wait for the book to be published, though. I think I might have annoyed some of my friends by how much I was trying to fling pages in their faces.”

“The book was originally going to be less than 200 pages. It ended up being around 300. During the final six months or so I started to use a wall of my studio to put all the layouts on. I knew I had to keep it under 304 pages so I kind of worked backwards and re-worked some of the layouts on there.”

Because it’s a graphic novel, the book afforded different opportunities in storytelling. There’s more room to plot, more room to draw out certain sequences or play with the storytelling format in comics more than in his previous works. The structure of “The Wrenchies” alone is so different than “It Will All Hurt” or “Omega,” or even Dalrymple’s first popular work, “Pop Gun War,” all of which feel like completely different books despite the fact that they feature the same illustrator. Dalrymple’s work has often been noted for his particular blend of characterization and dream-like worlds that they live in; both seemingly simple in their creation and complex in their creation, Dalrymple’s art has a notably surreal quality to it that has been dominant in his work — at least since I’ve come across it.

In fact, speaking of “It Will All Hurt,” it’s the obvious spiritual successor/predecessor. “It Will All Hurt” is a stream of conscious thought comic, like the Adventure Time of your nightmares, but it and “The Wrenchies” share similar aesthetics and post-apocalyptic vibes. Both books are littered with debris, flies hovering around the edges and monsters hidden in plain sight, featuring the characters and worlds that Dalrymple has managed to develop all of his own, despite being based on popular tropes. These are worlds unlike others of a similar ilk, with more beige and muted, mustard browns colored by all the toxins in the air, and each feature heroes who aren’t quite sure they belong, and neither are we.

A big part of this is just how Dalrymple developed his craft. “The cartooning just developed naturally over the years from drawing often — some from life, some from out of my head and looking at a lot of other cartoonists, illustrators, and fine artists,” Dalrymple noted. “Style isn’t something I think about too much. There have been some deliberate stylistic choices but with me I think style just happens mostly from making art everyday. A big reason I started doing “It Will All Hurt” was to get back the fresh and fun part of making comics without thinking too much about everything.”

And despite the similarities between “It Will All Hurt” and “The Wrenchies,” the construction of the two couldn’t be more different. As Dalrymple notes, “I tried to make “The Wrenchies” exciting and layered, but it was way more planed out and heavily processed compared to the “It Will All Hurt” stuff, which I draw straight with pen and don’t plan out more than a couple panels at a time. It wasn’t as hard as doing a work for hire type situation because I had the story mostly in my head before I started drawing it, but it did have it’s own set of problems when I was getting close to the end trying to make it all fit together in a way that made sense (at least to me).”

“I had a loose plot to work from and would try to thumbnail and layout each chapter or at least ten to 20 pages at a time. Once I got to the last couple chapters it got a lot harder to fit everything in. I had a file that I kept adding ideas to since the start of the book, so by the time I got to the Sherwood chapter a lot got left on the cutting room floor,” Dalrymple explains. “Well, not entirely left there; I swept it all back up into the file and am probably going to use most of it for a sequel.”

Continued belowBecause you see, “The Wrenchies” is a fairly complex book. Following the stories of quite a handful of characters along about five timelines that intersect in different and often ethereal ways, “The Wrenchies” challenges most storytelling conventions as often as it does the concept of reality. We have the Wrenchies themselves, via two different generations/iterations. There’s Sherwood the creator, Hollis the young boy, and a future Scientist whose knowledge of the world’s fate is uncanny and foreboding. But the way these characters have to interact is a unique one, and one that finds the characters clashing as often as it does collaborating — and because of this, everything that we understand about the book inherently comes into question.

A central tenant of the book is it’s affinity for playing with perception. Whether it’s early-on with the “It Will All Hurt”-esque fluid storytelling or the mind-bending finale that clashes what we know about reality against the fictional realm Dalrymple created, this is a book that asks a lot of questions and doesn’t necessarily answer them, nor does it take a strong stance on what is real and what isn’t. It straddles that line and the typical genre notions to the point where they’re near indistinguishable from one another.

“The Wrenchies” is a sci-fi book, but it’s also not. It’s a fantasy adventure, but it’s also not. It is challenging, both in that it seems to provoke genre deevices and it demands a lot from the reader, but as I mentioned earlier, “The Wrenchies” is many things all at once, poured into and mixed together in a blender on high — and the results are certainly highly imaginative to say the least.

“I don’t think the universe is clearly defined, the real one or the one I make up,” Dalrymple responded when I asked a question similar to ‘where do your ideas come from’ (not that exactly, but I certainly realize in the aftermath that it had that vibe). “”The Wrenchies” isn’t hard sci-fi or a traditional fantasy story; I see it more as metaphysical and a little psychedelic. I have a lot of ideas about the way that world works but I like making changes and adding things as I go. I feel like having magic be such a big part of “The Wrenchies” is a good way to get around some tricky plot holes and paradoxes you might run into with real science fiction. That was a big reason I decided to have The Scientist character do so much exposition in his chapter. There is that Arthur C. Clark quote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.“

But, aside from the reality bending and the complexity of it all, one thing that stands out in “The Wrenchies” — that sits right at the heart of it — is the aforementioned character of a young boy named Hollis. Hollis represents the average reader of comics within the story, the relatable centerpoint to the madness that circles everything else in the book. Hollis is the most meta-aspect of the book, our guide throughout the wasteland. Where most of “The Wrenchies” allows us to follow the madcap adventures of crazy teens surviving on a ruined planet, Hollis is the our point of reference as the eternal outsider, someone who wants to enjoy the journey but is afraid of the consequences. “His chapter and his character is the heart of “The Wrenchies,” Dalrymple adds. “He is the little kid in me. The fantasy scenes were fun to draw but if I didn’t have that little guy in there I don’t think I could have retained interest in the story.”

“Writing Hollis was natural and very satisfying to me as an artist. It was like he was the touchstone for the real world and the fantasy world and I don’t think I could have made the story work out without him.”

Since we have that relatable point, though, the balance between what is ostensibly real and what is not becomes that much palpable as things cascade together. Hollis is our mirror, and he’s the one we fear for the most; most of the Wrenchies gang feels like they came right out of Beyond Thunderdome, and the consequences of this are what you’d expect. But Hollis does very much represent the beating heart, and with him Dalrymple manages to create a different sort of attachment between the reader and the material. Most of the characters within are inherently cool, but their best aspects don’t come necessarily from their personality (something which at times seems to be based out of a future-punk hivemind); Hollis is entirely different.

Continued belowAs such, this represented an active challenge for Dalrymple, who himself is somewhat mirrored in the book with the character of Sherwood. There are characters like Hollis who we can find ourselves in, and then there’s the ones that we are eternally outside of, which creates an interesting balance within the story that’s something Dalrymple is very much figuring out as he goes. “I am still trying to figure that out that balance. My working/writing process is not pretty, a lot of me rolling around on the floor and pulling out my hair whining about how hard making a book is. Towards the end, when Sherwood is having his breakdown, it got very hard on me emotionally and took a toll on my personal life. I try to do some meditating every day and I am aware of how emotionally reactive I can be, but just trying to re-read “The Wrenchies”… It is hard for me to keep from tearing up. Maybe I put too much of myself in there but hopefully the more fantastic aspects of the story will be diverting to most readers?”

“I really tried to make myself enjoy the journey, but as I went through each spread it felt so good to put a big red “x” thought the layouts and have a visual finish line. One of the toughest things about the whole process was my having to work on other stuff to pay the bills. It was annoying and distracting to be shifting gears like that every few weeks. But now in hindsight maybe that was ultimately a good thing and helped make a stronger work by shifting my perspective so much throughout.”

So ideas clash and some things in the book are tough at times to fully reconcile, particularly in trying to define to yourself what did or didn’t happen. That’s arguably one of the biggest challenges of the book: it’s easy to relax and accept things from a page to page basis, but there’s also a fair deal of “The Wrenchies” that you’ll have to define for yourself by the end, for better or worse. What is real? Where did Hollis go? What really happened to Sherwood, let alone Orson? And what about the Wrenchies themselves; what is reality for them? There may be distinct answers to these questions, but if there are the book holds them tightly to itself.

Which, of course, isn’t to say that the book is inconsistent or doesn’t hold-up. It is, after all, the first book of a planned trilogy, as Dalrymple notes. But, like life and our time in spent in dreams, “The Wrenchies” plays by rules that don’t necessarily make sense — nor does it really have to. “So much of the real world is confusing to me, so like real life “The Wrenchies” could never make sense if you try picking at it. I mean, it makes sense to me but it is sort of like dream logic and more about the atmosphere of the world rather than trying to come up with a list of rules about how this world works. I really like the way those first few Stephen King “Dark Tower”/”Gunslinger” books made me feel when I read them. The same goes for the work of David Lynch. I don’t care if I understand it entirely, I just really enjoy the rides those guys take me on.”

And it’s no surprise the complexity when you look at some of the influences. “The Wrenchies” has many similarities to alt-fantasy/coming of age staples like “the Neverending Story” or “the Phantom Tollbooth,” but Dalrymple’s influences are much bigger than that. “Both those things were in the inspiration bag for sure, as well as Heavy Metal magazine and Moebius’ “Airtight Garage” and old Marvel comics too. One big influence, mostly with the way the kids interact with each other and their world, is the 1979 film Over the Edge. The old Star Trek episode “Miri” (one of my favorites) was also a springboard of their development. Mike Mignola, Tom Herpich, and Brandon Graham are all cartoonists I look at a bunch too.”

“A big thing I was trying to do was mix in a wide variety of different books/movies/weird TV shows I liked and sort of half remembered from my youth. Hopefully that all adds to the dream-like quality I was going for.”

Continued belowOne of my favorite lines in all of fiction is from “Lord of the Flies,” where Ralph says “You’re breaking the rules!” and the reply is “Who cares?”

To me, this line summarizes a lot of what I think makes “The Wrenchies” work. There’s a structure in place, but it’s more freeform than that; it is a comic book that adheres to some ideas comics have been home to, but for the most part Dalrymple seems more interested in breaking standard narrative conventions as a product of the creation process of the book.

“Not that are really any defined rules on how to make a comic, but yeah, I knew I wanted to shake up people’s notions of what a comic book can be with “The Wrenchies,”” Dalrymple said. “I tried to layer the story and hit on some deep themes while also having it be fun to look at. Each chapter, I wanted to tell in a slightly different style. I worked on the book for five years and I don’t know if most people even notice that sort of thing, but I figured from the start that the first page of the book would be different from the last no matter what I did.”

“I decided to be deliberate about changing my process a little and the paper I used from chapter to chapter to make it a little more obvious. Panel layouts too. All the panels that take place in the post-apocalyptic future are rounded corners while the more “real world” Hollis and Sherwood chapters are squared corners. Even the storytelling techniques like having the Sherwood’s chapter be third person narration, the Quest and Hollis chapters first person narration sort of (his talking to God), and the rest of the book not much narration at all. There is a bunch of little things in there like that that I wasn’t sure if people would notice. I even put a little flip comic in the last chapter because I thought it made sense with the story and would be a fun thing to throw in a comic.”

“The Wrenchies” is many things. To me it’s everything we’ve discussed so far, and to you it might be something else. In many ways, that seems to be the ultimate point of the book, which is full to the brim with different ideas that mix and match and clash and blend together. There’s quite a lot in this book, explored across conflicting timelines starring characters that don’t quite all fit together, but all of this and more — right down to a secret and (at least to me, at time of this writing) somewhat indecipherable code — makes “The Wrenchies” one of the most exciting and unique graphic novels out this year.

“I like the idea of people re-reading something and discovering new things. That goes along with the whole ”secret code” thing in the story, like the reader is deciphering his own magic spell. I was happy that First Second encouraged me and let me do all those sorts of things instead of just wanting a more straight ahead formulaic approach.”