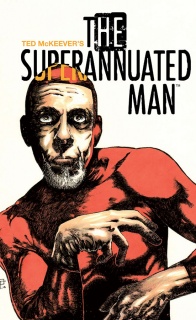

Humanity’s gone. Dead and in the dirt, leaving mutants to inhabit and roam the town of Blackwater. Mutants, and a dude in a scuba suit. Welcome to “The Superannuated Man”. Check out our spoiler-free review below.

Written and Illustrated by Ted McKeever

FROM THE CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED CREATOR OF MINIATURE JESUS.

By the time most people realized it, they were no longer in charge of the world we know. In an unspecified future, the small seaside town of Blackwater has now been taken over by advanced and mutated animals. Most of the humans that lived there are now either dead or gone, but one old-man remains, scavenging off the scraps and refuse of humanity’s past, and doggedly defying the new tenants.

“It was the Law of the Sea, they said.

Civilization ends at the waterline.

Beyond that, we all enter the food chain,

and not always right at the top.”

With that quote from Hunter, Ted McKeever gives us a concise description of the world of “The Superannuated Man”. After some unspecified event, humanity has become obsolete (or superannuated for you spelling-bee freaks, out there) and now, with a dwindling population, must survive by hiding from the mutants that have popped up and taken their place. Civilization has gone beyond the waterline and now humans have fallen from the top of the food chain straight into the water where they hide from the fucked up monsters that look hideous and talk in ways that just really don’t make any sense, speaking like they’re a mix between Blackbeard’s pirates and extras on The Wire.

That last quirk among the denizens of Blackwater does make for an uncomfortable read sometime, but with a purpose. The eponymous superannuated man is obsolete, he’s been in the game for too long. Without making any judgments, the same could be said for McKeever himself; not because he’s untalented but because the guy on the cover looks just like him. With that context, “Superannuated” takes on an interesting deeper meaning. The monsters surrounding our crazed hero (I don’t care how cool your wetsuit is, living in a shack and talking to a statue does qualify you as “crazed”) are scary not because of their deformities (though we’ll get to that in a minute) but due to their certainty. They belong in this world, he does not; it’s theirs now. This is the sort of terror that supposedly wracks people in the throes of a mid-life crisis (I wouldn’t really know, I’m not old enough to drink) and it elevates the horror in “TSM” to something beyond the face-value Eldritch abominations.

By posing himself as a superannuated man (and really I hate to be the one to impose authors upon their creations but seriously they look the exact same), McKeever seems to be expressing his fears that he’s being replaced by a new generation he doesn’t understand and, therefore, has to adapt to their ways, sometimes by taking on their form as seen when he scares away some youths by wearing a diving mask that makes him look like the fucked up creatures that took over his home. Unfortunately, by illustrating a story with themes revolving around the superannuation (is that right?) of artists like himself, McKeever seems to be showing a lack of courage which is completely unfounded because, real talk, this book is gorgeous.

By illustrating exclusively in black and white, McKeever gives the dilapidated city of Blackwater plenty of playing space. Horrific monsters jump through the darkness to attack citizens who look just as disturbed as they do. The town itself becomes a shimmering uncertain place, defined as much by its opaque alleys as its open streets. And when the aforementioned creatures come out they look monstrous, slimy disgusting things that dwarf our scrawny protagonist in both size and presence. Really, it’s no wonder why the titular character feels so obsolete compared to these powerful, disgusting beasts. If McKeever also sees these horrors as the new wave, as a new group that will overcome him, then he’s out of his mind because with the way he confidently establishes a world. it’s clear he hasn’t really lost any of the talent that’s supported him through the years.

Continued belowUnfortunately, I’m not too entirely sure how much this book can live on the contrast between humanity and the monsters that now rule the world. While there are a ton of great character beats, this seems to be the sort of book that lives or dies by its central metaphor and it’s one I don’t entirely agree with, at least not from just the first issue. McKeever unfairly portrays the newer generation as monsters with, frankly, kind of offensive dialogue that are looking to do him in. While that’s an issue clearly taken up to eleven (as are most issues in comics), McKeever practically proves it false with “The Superannuated Man” #1.

As one of the “monsters” that are supposedly out to get older people, I enjoyed it. Though some people might find a greater resonance with the fear at the heart of “The Superannuated Man” I found it rather benign; a rant uttered by a talented artist who would do good to focus less time writing about the monsters coming to get him and more time working with the monsters that make his book so compelling.

Final Verdict: 6.8 – Browse. This is definitely a book to keep on your radar.