Nick Drnaso has shown a gift for depicting how the quotidian quality of life masks, and then reveals, the dark fissures in our society. Two years ago, “Beverly” served as an abrupt revelation of that talent. Now, “Sabrina” (Drawn + Quarterly) sustains it in a troubling triumph of that contemporary unease that comics can insinuate on its readers with distinctive potency. “Sabrina” is a stunning graphic novel that explores Western society’s freshest wounds, the simmering suspicions of our neighbors and ourselves, exacerbated by the alienating dislocations of our mediascape, but presented with its own bare-knuckled tenderness about our quiet humanity.

Written and Illustrated by Nick Drnaso

Where is Sabrina? The answer is hidden on a videotape, a tape which is en route to several news outlets, and about to go viral. A landmark graphic novel, already hailed as one of the most exciting and moving stories of recent years, Sabrina is a tale of modern mystery, anxiety, fringe paranoia and mainstream misinformation – a book that tells the story of those left behind in the wake of tragedy, has important things to say about how we live now, and possess the rare power to leave readers pulverised.

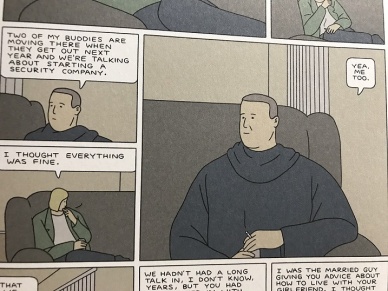

Sabrina and her sister talk about pizza, cats, reading, boyfriends. Drnaso’s airplane-safety-card style drawings echo the minimalism of the conversations. An entire page is devoted to the rote motions of Sabrina going to bed and waking up the next day.

But in the yawn of a few pages’ silence, Drnaso sacrifices Sabrina to the profoundest of modern horrors, all off-camera, which we gradually realize, upsetting our whole safe sense of the mundane: Sabrina disappears, and her fate is the sum of our worst current fears, captured on video and broadcast all over the media, another rip current in our contemporary bombardment of violence and inhumanity.

We never see the act, in Drnaso’s signature understatement. But we read its ripples in the deceptively simple faces and plaintive situations of its survivors: Sabrina’s sister to a limited extent, but most of all, her boyfriend Teddy. Running and coping from the nightmare of his girlfriend’s vanishing, Teddy turns to old high school friend Calvin, a military man at a desk job who welcomes his traumatized houseguest into a bedroom vacated by his daughter and recently separated wife. Again, these details are as everyday as could be. But every one of those details plays into Drnaso’s grand orchestration of tensions, note after turgid note, beneath his flattened and pastel 20-panel pages that depict the simplest daily life, laced with dread.

It’s a haunting and masterful rendition of our times. These days when we sit to eat dinner with our families, and we pick up our phones to find out about another mass shooting in a mall, or a school. Unspeakable brutality bursts into our day jobs, our bowling alleys, our drives to the grocery store, hanging like a deep chill in our bones on a summer day.

That’s the creeping dread that suffuses “Sabrina,” and it must be read to be understood. Without giving away where the story goes, naming a few more elements of how Drnaso orchestrates that perfect and terrible tension should resonate with readers who have already absorbed the book, without spoiling the dramatics for those who still haven’t had the pleasure, if that’s even the right word for the experience. Whether you’ve read it or not, let me just lay cards on the table that this is almost certainly one of the most significant graphic novels of the year, if not of the past several years.

At least part of its impact rests on Drnaso’s exploitation of the comics’ literary legacy of showing life’s word-scarce rhythms, inherited through visual virtuosos like Frank King and Chris Ware, in stark relief from our word-filled social lives, ironic juxtapositions mastered by creators like Bechdel and Tomine. Many key scenes of this book occur while Teddy and Calvin appear innocently lounging at home in their underwear (or Snuggies), Calvin doing his darnedest to manage his friend while his own life slowly slides into devastating loss.

Continued belowAnd with similar terseness, we witness Teddy’s emotional paralysis, barely able to leave the house let alone resume normal jobs and relationships, becoming its own tinderbox of timely fears. Those fuses are lit by Teddy’s constant attention to the monstrous verbosity of an Alex Jones-like conspiracy radio talk show, a reality-bending monologue of ideological distortion pounding his frail psyche. The powderkeg, a set of firearms that Calvin informs him early on that he hides in the house. Drnaso fiddles with our trivializing of guns as Chekhovian story devices in times where, no matter how securely owned and locked up, they pose clear and present mortal dangers that are all too real.

Undergirding these fears of our weapons and what we do with them, be they guns or ideological assaults on our perceptions, is the rampant mistrust that corrodes our natural yearnings and inclinations towards community. Don’t be fooled that the lengthy exchanges between characters go nowhere or say nothing. They all reach towards connection. The aching for connection beneath the mildest repartee between characters screams what Drnaso’s subdued characterizations only whisper: in the wake of our rounds of self-induced trauma, we desperately need each other.

But can we trust each other? Drnaso craftily harnesses our paranoias. Characters appear like landmines. Slow moments we might otherwise find quaint, instead we read into with portent. Like a million stories have taught us, whether fictional or frighteningly factual, we find ourselves unsure whether to love or to fear these characters we watch so intimately.

Worst of all, we realize that skewed paranoia is exactly how we feel in our real lives, among our own friends, coworkers, and neighbors. By being so banal, the stewing tensions under “Sabrina” present a disquieting mirror.

Never onerous but continually affecting, never skimping but narratively propulsive, “Sabrina” is a masterpiece of late 2010s comics texts, a time when an old medium has tremendous power to grind the gears of the new, to make us reconsider our deepest anxieties by drawing us into our simplest self-recognition.