Sometimes, the weight of a previous work looms ominously throughout the experience of taking in a cartoonist’s latest work. That’s not a universal thing, and it’s entirely dependent on the person reading the work, but for some, it’s impossible to take in a book without contemplating the cartoonist’s past. A good example of that was last year’s “Seconds”, Bryan Lee O’Malley’s follow-up to his beloved “Scott Pilgrim” series. With that book, it seemed as if people didn’t just wonder “is this book good?”, they wanted to know “is this book Scott Pilgrim?” The creator became inseparable from the work that preceded him.

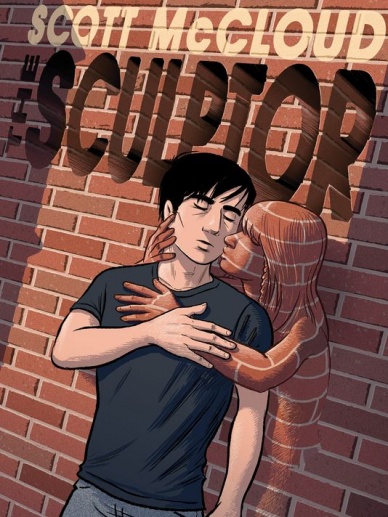

Scott McCloud’s “The Sculptor” is facing a similar situation, if not exactly so. McCloud has long been one of the preeminent comics theorists thanks to his work on books like “Understanding Comics”, a comic that helped explain and enhance appreciation of the medium as any comic before or sense in its own way. After three books in that vein and years as a lecturer on the subject (having seen him speak on his 50 States Tour, I can personally attest to his gifts as the latter), he’s finally back with a complete, original story, and naturally, his work studying the art form is deeply contemplated in every read and review.

Here’s where I tell you, throw those expectations away. Just because Scott McCloud is a master at understanding comics and how you can use varying methods to manipulate time and emotions, doesn’t mean his book will be filled with tricks of the trade. To think that would be to misunderstand his work as a comics theorist. “Understanding Comics” wasn’t about how you can use innovative panel layouts to convey story. Rather, it was about the simple wonders of the art form, and how tremendous it can be as a storytelling medium. And “The Sculptor” is a wondrous example of everything the medium can be, telling a beautiful, tragic and affecting tale over the span of nearly 500 pages that enhances your appreciation of the import and cost of love and art.

One of the most incredible things about this graphic novel is its deep understanding of the cost that comes with achieving greatness with your work, and the reality of what that even means. If “Understanding Comics” was about the capability and craft of art, then this book is about understanding what attempting to actualize that can do to you and the people around you.

The book is about David Smith – the other David Smith – a once up-and-coming sculptor who has since lost his way and found it at the bottom of a bottle and within questionable offers. What would you give if someone could give you everything you always wanted? How far would an artist go to realize their dreams? That’s the question at the core of this story, and it permeates through each and every element of it.

One of the most interesting things McCloud does in this book though is by digging into the Venn diagram that exists between the ideas of a person as an artist and as a human. Smith knows what he wants as an artist. He wants people to remember his work. He wants people to be moved by it and to be stunned by it and to be considered great. But so much of the emotional weight of this story comes from the simple fact that he has no idea what he wants as an artist that is also a person. What moves him? What would success look like, and what would it feel like? As with so many books built around desirable deals with a huge cost associated with it, over the span of the story he realizes that what he valued before wasn’t necessarily what he truly valued, but what he always imagined he should value. It leads to deep questions about art and identity, and the way McCloud tells it delivers everything about it with maximum impact. You can’t be an artist without being a person, and without appreciation of the latter, it’s hard to succeed as the former.

This is all built around and in David Smith’s life after a deal is struck to help reach his undeveloped dreams, and what happens when he meets someone that helps him find that center part of the aforementioned Venn diagram. Meg, the other main character of the story, easily could be written off as one of the much maligned manic dream pixie girls that have existed for oh so long in fiction. However, she’s much more than that, as McCloud writes her as an artist and person who struggles with her own identity and goals and needs as much as Smith does. She goes beyond the trope into her own ball of complication and beauty, not existing solely as Smith’s muse, which is important in making her not just a valid component to the tale, but an important one. A big part of that comes from the dedication of the story I believe, which you can read about in the afterword to the book, but it’s clear that Meg isn’t just a manifestation of one man’s desires, but living, breathing person in this reality.

Continued belowWhile much of the book follows pretty straightforward, standard comic layouts – as I said, just because the guy’s a master of them doesn’t mean he’s going to perpetually rely on trickery to tell his story – it is worth noting that there are some bits of resplendent, unique and utterly engrossing breaks of form within the book. Some are subtle, like when Smith first discovers Meg and the thick, white panel breaks are replaced by thin, black ones to help increase the tension and sense of urgency. Others, like the 16 page crescendo towards the end of the story (you’ll know it when you see it) that hits like a punch to the gut thanks to the way McCloud delivers it, are much showier, but not in a way that feels designed to be that way. They stand out because of how incredible they are, not because they’re designed to do so.

It’s moments like those that make McCloud’s background stand out. His craftsmanship as a cartoonist is unparalleled thanks to his abilities and history as a comics theorist, and moments like the ones mentioned above make this book as emotional of a read as I’ve had out of a comic in quite some time. Thanks equally in part to his cartooning as it is to the actual plot, your heart gets a serious workout in this book, and I’m not above admitting it got a little dusty in the room when I was reading this book.

The whole book is colored in a light blue ink, not unlike last year’s “This One Summer” from Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, and like in that story, the minimalist tones and purity of focus keep the reader centered on the storytelling to the benefit of the comic. It’s a good choice, one of many McCloud makes when it comes to the art of the book, and it enhances the storytelling even as it properly fits the occasionally funereal mood.

To say Scott McCloud’s “The Sculptor” is a good comic is to perhaps understate things. Like “Understanding Comics” exists as an explanation of how comics work, “The Sculptor” is a perfect example of what the art form is capable of. It’s a work that sticks with you well past your closing of the book, and will exist in the future as one of the books people lean on as what comics can be at their best. In a way, this book is proof that Scott McCloud isn’t his titular lead character. He’s a man living at the center of the Venn diagram between artist and human, with his humanity enhancing his craft and helping him create something that both he and his readers can appreciate wholeheartedly.