Lithuania spent the 20th century in a series of occupations and movements for independence. “Siberian Haiku” takes place in the exact middle, starting in June 14, 1941, when the occupying Soviet Union quickly deported some ten thousand people to Siberia. Families were broken up, and sent to different labor camps and collective farms.

Then, years later, many children were returned on an orphan train. A unique occurrence in the forced migrations of the Soviet Union.

This is all historical background that’s useful for understanding what’s happening, but also not strictly needed. “Siberian Haiku” doesn’t directly say any of this. Much like “Maus”, this non-fiction story is told entirely from the recollections of the writer’s father, Algis. It’s his story, and everything begins and ends with his childhood memories.

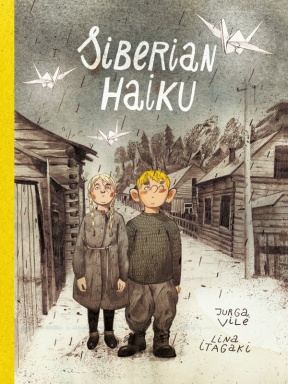

Written by Jurga Vilé

Illustrated by Lina ItagakiJune 1941. A quiet village in Central Lithuania awakes to the arrival of the Soviet Army. Young Algiukas’s family is given barely ten minutes to pack before being herded onto a crowded freight train bound for the snowy plains of Siberia. Leaving behind the fertile agricultural lands of rural village life, they are forced to adapt to living in these brutal new conditions. Whilst this life quickly becomes a battle for survival against hunger and the relentless cold, Algiukas learns to escape the daily rigours through the inventive power of his imagination, with the help of pencils, paper and a book of Japanese haiku poems.

Based on the true story of her father, writer Jurga Vilé, along with artist Lina Itagaki, offers an unforgettable tale of a childhood in exile. In the process, they shed light on one of the darkest periods of European history that, seen through a child’s eyes, underlines the courage of human endurance.

The book is written and illustrated like a children’s book. (Which makes it the second dark children’s book I’ve reviewed in two months.) Every page is hand drawn with pencils, and maybe pastels. I don’t think a computer touched this art. Great, light-hearted illustrations and hand-written text underly some of the darkest content available. The children’s art style looks more like Emil Ferris’s “My Favorite Thing is Monsters” than a traditional comic book.

This children’s book inspirations is great choice by Vilé and Itagaki. It gives this book a refreshingly different flow and approach to story telling. For example, there’s no hand-wringing here about “showing versus telling.” Every time a new character enters the story, Vilé takes a page to simply tell us who they are in a nice black and white vignette. That’s something Algis would know, so we do too.

Similarly, Algis and his family write a lot of letters to their now-distant relatives, asking for help, or inquiring about life, or simply saying hi. A normal comic would show a character writing or reading these letters, panel by panel, showing the emotion in their face as they think of each word. Here we just see the actual letter. Not being help by anyone, just presented on the page like a historical document.

The children’s book approach to story-telling is more immediate, and without clever devices. We still have plenty of room for deeper messages, and metaphors about fertility and agriculture and death (all through apples), it just isn’t hidden under artifice.

And on occasion we get a full-page architectural rendering, done with a childlike looseness, simply because it’s a beautiful sight that Algis sees.

Siberian Haiku also has some simple instructions. Like how to fold a crane. I never see that in a traditional comic.

Or how to make Stone Soup.

Now there’s an old fable about stone soup, where some poor travelers trick the townsfolk into helping them cook a delicious meal. This isn’t that. The stone soup in Siberian Haiku starts with water and a stone, and barely contains more than that. But that’s life in Siberia. It’s a world of hunger and lice and bedbugs, and where apples don’t grow, even lovingly cared and watched over. “Our empty stomachs make interesting tunes,” Algis says.

It’s a world where the guards can cancel Christmas, which is a like any other day but with a bit of bone flour in the soup.

Continued belowBut Algis is a kid, and kids accept and survive the world that is presented to them.

Early in his forced migration, Algis is given a sheet of pages to write letters on. I mentioned these letters earlier. We read a lot of them. But there are no postal workers near him, so he writes a name and a city on the front, and throws them to the wind to be carried by the ghost of his pet goose.

At the end of the book, his uncle greets him in the orphanage with a sack of golden apples. “How did you know I missed apples so much?” Algis asks. “You never stopped writing about them!” his uncle says.

There’s a magic here. A story told through a survivor’s mind, like “Life of Pi.” And who am I to question it?

I’ll end this review with a small story of my own. I once visited Washington DC with a friend and his kids. I, having been raised Jewish, was making plans to visit the Holocaust Museum, and he, a gentile, declined to join me. “You should come,” I said, “there’s a kids section.” He looked at me. “That’s a bit dark for them, don’t you think.” My mind went blank. I couldn’t understand the statement, it’s like he just told me, “up is down.” How can anything be too dark for kids? Being raised Jewish means my life was filled with children’s books on the Holocaust. How can anything be too dark for anyone?

Siberian Haiku is children’s book on a frightening moment in history. It’s a small one that’s not well known outside of Lithuania, but one that should be kept in the world’s memory. It’s a story that could stand for any of the millions of forced migrations in the USSR, or by any nation. It’s also a story told by a child. That’s a contrast I’m very comfortable with, and I’m comfortable recommending it to anyone of any age. Especially children.