This week, we are offering reflections on the six nominees for the 2015 Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work, while contemplating larger questions of the variety of ways comics can uniquely crystallize reality for readers.

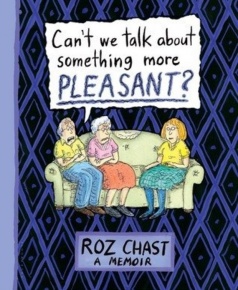

Written and Illustrated by Roz Chast

Published by Bloomsbury, Color, 240 pages.

In her first memoir, Roz Chast brings her signature wit to the topic of aging parents. Spanning the last several years of their lives and told through four-color cartoons, family photos, and documents, and a narrative as rife with laughs as it is with tears, Chast’s memoir is both comfort and comic relief for anyone experiencing the life-altering loss of elderly parents.

In recent years, in my mid-thirties, I’ve had occasion to confront painfully (and sometimes comically) difficult end-of-life questions in my own family, and found myself totally unequipped, lacking even peers dealing with similar issues to commiserate with about things like palliative care or powers of attorney. Thankfully, in my disquiet and discombobulation, a few friends have piped up about caring for their elderly parents or their all-too-short bouts with a loved one’s terminal cancer. Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talked about Something More Pleasant has changed hands in some of these interactions, a life raft on the lonely island of parent care in a culture of elder neglect. With the humor that only comes from frankness and the frankness that’s only tolerable with humor, Chast recounts the dilemmas and absurdities that plague her while trying to take care of her elderly Brooklyn-bound parents.

In doing so, the “reality” Chast leverages for comic storytelling are the topics of not only personal and subjective consequence, but the widely shared dusty corners of contemporary life that we typically avert our eyes from. Chast’s cartooning somehow matches her unpleasant subjects in the same wry way that a Gahan Wilson or BEK cartoon somehow fits sharing a New Yorker page with an article about climate change or the Rwandan genocide: comics with no intention of running from realities, but instead of raising them uncomfortably, comically, court jester-like, right in the middle of the conversation.

Thus, Chast’s book has become one of my favorite gifts to give friends similarly looking forward to life’s latter half, though I’m not really sure any friends are glad to receive it. Until they read it, of course. Chast’s book prefers not to talk about something more pleasant because the richness, comedy, and pathos of cluttered drawers, Ensure, and colostomies is unrivaled comics fodder. The experience of reading the entire book, of laughing with eyes rolled at her father’s quirks and mother’s temper, of stings of empathetic loss, of bewilderment at the impossibility of rationalizing a loved one struggling with senility, is an experience of tasting Chast’s reality. I daresay I’m better able to take my own parents’ inanities and sensitivities with healthy grains of salt after reading this book.

Could that be one of comics’ unique gifts, the saltiness they sprinkle to ease hard subjects down our throats? Pekar and Brabner’s 1994 Our Cancer Year and Fies’ 2009 Mom’s Cancer manage similar feats, not to mention Nate Powell’s Swallow Me Whole, Ellen Forney’s Marbles, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and the many other great books I insult by excluding. No matter how high up flights of escapism the comics may take us, in the end their primogenitor is not Nemo in Slumberland but the Yellow Kid, whose caricature figures in newsprint colors exacted trickster revenge on the realities of race, class, and New York tenement harshness, the way Chast’s caricature figures in newsmagazine colors channel therapeutic relief on the realities of anxiety, death, and New York tenant retirement. Sometimes I think I read comics specifically to escape from the emotional burden of topics like this. Yes, I would prefer to talk about something more pleasant, like inscrutable multiversal incursions or apocalyptic viral endgames. But Chast reminds us that “reality” in comics can often be the confrontation of the hidden, ugly, unpleasant, in everyday life, the muckraker of the mundane and prophet of the pedestrian, but with such liberal doses of self-effacement, shameless aplomb, and outrageous humor that we can applaud the exposure with gratitude.

Tomorrow we wrap this whole thing up with some thoughts on what reality based comics mean to the medium and why they’re worth celebrating. You can keep up with the entire week’s look at the 2015 Eisner nominations for Best Reality Based Work here.