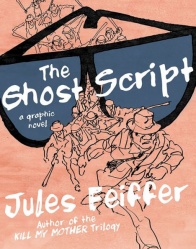

“The Ghost Script” (Liveright, 2018) is the third book of Jules Feiffer’s “Kill My Mother” trilogy, taking some familiar characters into adventurous American (and “un-American”) activities of the 1950s with artistic and literary aplomb.

Cover by Jules FeifferWritten and Illustrated by Jules Feiffer

Eighty-nine-year-old Jules Feiffer delivers the tour de force of his illustrious career in this epic finale that dares “to try things that film noir could only dream of” (Chris Ware). In The Ghost Script, Feiffer plunges us into the blowzy, boozy world of Blacklist Hollywood, circa 1953: witch hunts and Reds and pinkos and starlets and a mysterious, orchid-growing mastermind, the renamed “Cousin Joseph,” running a back-channel clearinghouse for victims of the entertainment world’s purge. Stumbling his way through this maze is private eye Archie Goldman, a tough-talking good guy, always a step or two behind in this fast-moving story of plots, counterplots, and goon violence. Meet Lola Burns, the buxom Blacklistee, desperate to get back into pictures, and O. Z. McCay and Fay Bloom, the booze-swilling, hard-living communist screenwriters. In this satiric assault on our past and present, Feiffer shows how the arc of American history evolves from starry dreams to thwarted and sold- out dreams.

What started to come apart in that mid-century period of US history, when America’s rise seemed to have all the roots of its downfalls? As a lead character of Jules Feiffer’s “Ghost Script,” Annie Hannigan, dolefully observes, “So this is what I brought into the world. A son named after my Father, a great man who only wanted to do good for his family– and his country. / And his namesake, my son– / has a swastika framed on his bedroom wall”? Somehow, Feiffer’s 1953 America is cannily true of its time, yet uncannily reverberates into the America we struggle over today.

One way that comics — a meeting point of popular, artistic, and literary culture –s erves a vital social role is to recall and reinterpret history. Not dusty, irrelevant textbook history. But as Jules Feiffer shows us, history vibrating through idiosyncratic brushstrokes, through pockets of storied secrets and investigated surprises, and through brutal words and friendly beatings between political allies and enemies high and low. In “Ghost Script,” these complex webs are masterfully woven by the hands of one of comics’ living legends, known for his long-running strip “Feiffer” from the Village Voice, onetime assistant to Will Eisner, first seen by many in my generation as the illustrator of The Phantom Tollbooth, and indisputably among the most important American cartoonists. With “The Ghost Script,” Jules Feiffer completes a trilogy that has garnered attention in literary circles, but whose achievements I’ve seen too little recognized in the comics and graphic novels world. Let’s rectify that.

The first book, a graphic novel experiment of sorts for Feiffer, was “Kill My Mother.” This 2014 noir-ish tale was set in — and reeked of — the 1940s: the drunken PI, the Hollywood studio star, the USO celebrity performances for WWII soldiers in the thick of battle. But Feiffer has a proximity of memory to that time that puts to shame all those other comics that succumb to caricatures of retrograde race, gender, and class elements of that era and those genres. There’s authenticity in the agency of the story’s women, Elsie and Annie Hannigan (the titular threatened mother and insouciant daughter), operating from the angles available for them to screw the authorities or save the day. It’s a quirky romp with a lively cast equal parts expected tropes and unpredictable twists.

“Cousin Joseph” was Feiffer’s 2016 follow up, except it went the prequel route to delve back under the simmering politics suggested in “Kill My Mother.” Flipping the calendar back to the 1930s, Feiffer shows us Elsie Hannigan’s husband Sam (the aforementioned “great man”), a scarily misguided but earnest cop who is caught up in the fear and confused virtues of that period’s strains of nativism, paranoia of socialist movements, and mounting ideological battle over the cultural sway of movies amidst Hollywood’s rise. Like in “Kill My Mother,” the action is swift, the characters craggy and loose lipped, and the shoulder-rubbing between union leaders, Jewish kids from the Lower East Side, movie bigwigs, police wives, and mysterious conspiring forces keeps the sparks hot.

Continued belowNow in 2018, we get “The Ghost Script,” jumping forward to the 1950s of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Hollywood blacklist. Our cast of characters have aged to new roles, and Archie Goldman, who was a hapless kid in “Kill My Mother,” is now a hapless detective chasing down the title’s “ghost script,” a screenplay purportedly outing the buried truths about the anti-communist blacklists. Elsie and Annie Hannigan are still in the picture, albeit also in new positions in society, and others in the cast take the stage too (black reporter Orville Daniels, actress Lola Burns, cavernous Cousin Joseph…) Here, Feiffer seems to owe as much to his past playwright success as his cartooning chops, as characters march through the stage’s traffic with no wasted lines and exquisite timing and touch.

In one scene, the two-page chapter “Self-Loathing,” Archie Goldman lectures himself behind the wheel of his car in a bout of verbal flagellation, headlining himself as “The Wishy-Washy Detective.” But the soliloquy is just the simplest example of Feiffer’s extraordinary command of comics as a storytelling medium, borrowed back-and-forth with film, trading tools with theater, as a barrage of roving camera angles and a sequence of subtle shifts in expression carry us empathically through four swings of Archie’s evaluative pendulum in comparing himself to the memory of Sam Hannigan.

And all this nuance in a scene of a lone character in a car just indicates the degree of raucous fun and jittery wattage of Feiffer’s panoply of colorful characters, verbally duking it out while dancing ballroom, mired in car chases and murky murders on the docks, indulging in post-coital champagne and taut conversations, encountering card-playing communist screen writers in florid parlors and The Big Sleep-esque geriatrics in greenhouses.

Attempts to summarize “The Ghost Script” only make for incomprehensible circularity (as all plot summary of all good noir ought to be), but suffice it to say that thematic threads begun in “Kill My Mother” and loomed through “Cousin Joseph,” threads about the personal costs of loyalty, especially when imbricated in political tussles far beyond our individual control, wind up woven and, in surprisingly neat fashion, tied together in the fast-paced action of “The Ghost Script.” It might take some readers to get accustomed to the brevity of Feiffer’s two-to-four page chapters, the information readers have to assemble, connections left unsaid. I’d urge readers to start with “Kill My Mother,” which has a way of teaching readers how to understand it. Despite the similar-looking faces (intentional), the muddled motivations and uncertain trajectories of characters (also intentional), and the scrawling quality of Feiffer’s linework (to me, irresistible), the first two books of the trilogy set up most of the satisfaction and significance of “The Ghost Script.” But don’t be fooled. That satisfaction isn’t in a simplistic story, and that significance is exactly in how characters with many faces maintain perpetually uneasy relationships with the evasive social fabric around them. That’s the point, as they say.

As a kid of the 1980s, I spent a weird amount of time with the textual source material for “The Ghost Script,” from Milton Caniff comic strips to Elia Kazan accounts of HUAC era Hollywood betrayals, from Raymond Chandler novels to Ingrid Bergman’s turn in Notorious. Revisiting not just those renderings of the screen and page, but also the playful toggling between genre and history, with a master like Feiffer is a perfect reminder: There’s nothing like art to reflect back to us the creeping truth of the times, that all us detectives in pursuit of the past’s reality come back hopelessly again and again to the same mirror surface of misty dreams.