Welcome to this week’s installment of the Summer TV Binge of Netflix’s Dark, analyzing the eighth chapter of the twisted German time travel series, released December 1, 2017.

“As You Sow, so You Shall Reap (Was man sät, das wird man ernten)”

Written by Martin Behnke and Jantje Friese

Directed by Baran bo Odar

November 10, 1953: the bodies of Yasin and Erik are found dumped on the construction site of Winden’s nuclear power plant. Tronte Nielsen arrives in Winden with his mother Agnes, and starts lodging in the Tiedemann household. Egon Tiedemann and Helge Doppler encounter Ulrich searching for Mikkel, and Helge’s older counterpart.

1. Physics 101

This episode is framed by a conversation between the Stranger and H.G. Tannhaus at his clock shop in ’86, where they discuss the theories in his book A Journey Through Time. It lays out the show’s time travel rules and reinforces its themes: for instance, Tannhaus states there must be a third dimension to a Einstein–Rosen bridge, and suggests the traditional image of it having two entrances/exits is a result of classic binary thinking: likewise, Ulrich assumes by going down the tunnel, he’ll crawl out of the same exit as Helge.

The two consider the significance of 33 across history — amusingly, every example they think of is completely different from mine, including the supposed age of the antichrist when he begins ruling the world. We cut to Noah with the notebook bearing the triquetra — it’s not subtle, but it’s effective, indicating he and the Stranger are locked in an ongoing struggle (there’s that binary thinking again). Also, Tannhaus talks about how a wormhole would upend and distort all sense of a person’s history, just as the newly arrived Ulrich encounters his younger grandmother and father in 1953.

It also turns out Tannhaus’s own sense of history is warped: after his surreal family reunion, Ulrich goes to his shop, shows him Helge’s copy of A Journey Through Time, and asks if he was the man who wrote the book. He is, and isn’t, because he hasn’t written it yet, and Tannhaus is naturally alarmed to see his older self’s photo on the back of the book. When Ulrich hears about the bodies and charges off to the police station, he leaves his jacket with his phone inside: Tannhaus finds it, and is startled by it.

The Stranger reveals to Tannhaus that there is a wormhole in Winden’s caves, created by an incident at the plant “a few months ago” (which, given this show’s nature, still isn’t clear). He then unveils the gear device he carries, which he explains is a personal wormhole generator that allows him to travel independently 33 years into the past and the future — however, it’s damaged, and he needs Tannhaus to repair it. Tannhaus, shaken by old memories, asks him to leave. The Stranger leaves his machine though, and Tannhaus pulls a newer version off the shelf, confirming it is his work.

2. The Lodgers

Ulrich encounters his grandmother Agnes, and his father Tronte, when they stop and ask him for directions to the Tiedemann home, which turns out to be the future household of the Nielsens themselves. After their encounter with the confused man, they arrive at their new lodgings: while her mother Doris helps Agnes settle in, Claudia Tiedemann takes Tronte for a walk in the woods with her shy, timid friend Helge, whom she also tutors.

We’re witnessing the beginnings of what will become Claudia and Tronte’s affair, as well as Helge’s unrequited crush on her, which raises several questions — were Claudia and Tronte initially in a relationship? (We still don’t know who Regina’s father is.) Did Agnes taking ownership of the Tiedemann home break off the burgeoning relationship until they were adults? Who did Helge ultimately have a child with?

Claudia’s dog Gretchen disappears after an envious Helge throws a stick into the familiar “hellmouth.” Poor Egon, who’s already busy as part of the investigation into the unidentifiable bodies, has to subsequently go searching for the dog, not knowing the question is when she is instead. Young Claudia is left at the end of the episode looking forlorn; it’s just as well Tronte came between her and Helge.

Continued below3. The Good Old Days

The 1953 setting comes within touching distance of World War II, a catastrophe that the crew of the first German Netflix series likely felt was too predictable to mention, yet its shadow can be felt everywhere. Helge’s father Bernd — who presumably walks with a cane because of a war injury — continues holding a shareholder meeting on the site of the new plant despite the day’s gruesome discovery, a reflection of a nation struggling to move into a bright new future. Helge’s mother Greta is cold and distant, asking him to try on some new clothes by ordering him to strip, possibly a sign of PTSD.

Similarly, Helge is targeted by two older boys at the cabin, who want to send a message to his wealthy father. Both teenagers must’ve been part of the Hitler Youth, and conscripted during the final days of the war, so it’s no surprise they’re resentful towards an upper-class child too young to have experienced what they went through. Also at the station, the murder investigation leads Egon and a colleague to discuss if psychopaths are born or made, something that must’ve weighed heavily on everyone’s minds after the war.

The idealistic young Egon (played by Sebastian Hülk instead of Christian Pätzold), is a very sweet character: he’s visibly taken back by how beautiful Agnes is, and clicks his teeth at his colleagues for mocking Ulrich’s haggard appearance when he comes to the station looking for his son. He’s also old enough to have been in the Hitler Youth, or conscripted during the war, but he presumably didn’t become a true believer, as he’s bewildered by what radicalizes people: I suspect he was trying to show Germans could be better people after the atrocities of the war, and assumed everyone else would too.

It’s not just these bad memories that stress the post-war decade of the ‘50s was nowhere as tranquil as people pretend they were: Agnes tells the Tiedemanns her husband has died, yet the burns on Tronte’s arm in the closing moments indicate they fled from an abusive monster. When Doris and Agnes are making a bed, their hands meet, and Doris experiences a romantic awakening: a reminder that, although the Nazis were gone, this was still an era when everyone had to conform — or else.

4. The Darkest Moment

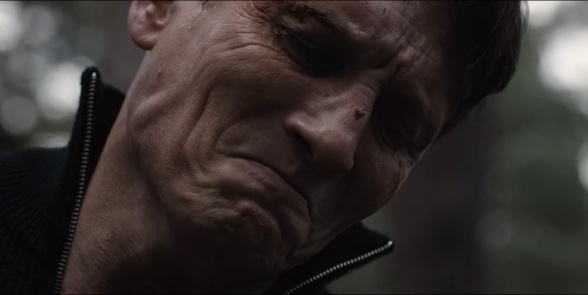

After asking Egon for directions at the police station, Ulrich finds young Helge at the Doppler mansion — the future site of the town’s hotel — and decides to kill him. Nietzche’s concept of the eternal recurrence is mentioned during Tannhaus and the Stranger’s conversation, but this recalls his infamous warning: “Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster… for when you gaze long into the abyss. The abyss gazes also into you.”

It’s utterly gut wrenching, to see someone so sympathetic consider something so evil: but Ulrich cannot possibly know Mikkel is alive in ’86, and he visibly struggles with the weight of becoming a child murderer to prevent another’s existence, until he notices Helge’s morbid fascination with the birds killed by the temporal disturbance. He doesn’t believe Helge when he says he only found their bodies: it’s a cruel irony that Ulrich decides the boy is a permanently irredeemable killer, just as the older Egon was willing to believe he would rape Katharina.

Ulrich bludgeons Helge with a rock, recalling the primal imagery of Cain and Abel, and explaining his scars. He places the boy’s body in the bunker, and waits for him to die of his injuries. But we know Ulrich has not ended the cycle, but only started it, just as Cain committed the first murder in the Bible. For the record, I strongly believe that physically punishing children subconsciously encourages violent behavior, and it is small wonder Helge came to value life so little when a stranger brutally demonstrated how worthless he was to him, at such an impressionable age. Since we have mentioned Hitler, it’s also a dreadful reminder that, no, going back in time and killing him would not have prevented the rise of fascism in Europe during the ‘30s.

Continued belowDuring their conversation in ’86, the Stranger asks if time travel can allow us to change our destinies, or if “we are nothing but slaves of time”: Tannhaus stresses that the causal loop would make it impossible to determine what exactly caused something to unfold. Ulrich sits hoping reality will be reset and that he’ll be reunited with his brother and son, but it’s clear karma has already punished him for his sin — his inability to express grief without anger has made him time’s ultimate slave.

5. Casting Notes

It’s interesting Ulrich participates in a scenario resembling the “would you kill Baby Hitler?” dilemma, given Oliver Masucci played the fiend himself in the black comedy Look Who’s Back (Er ist wieder da), where Hitler is mysteriously revived in the present day. The more likely in-joke is that Mads, Mikkel, and the Danish surname Nielsen were all nods towards Masucci’s lookalike from across the border, Mads Mikkelsen (something the German Netflix Twitter account has acknowledged).

On that note, Antje Traue (Agnes Nielsen) and Anatole Taubman (Bernd Doppler) were the only actors I recognized before watching the series: Traue memorably played Faora in Man of Steel, while Taubman is an incredibly prolific actor who’s been in everything from the Bond films to the MCU, and Watchmen (portraying Jon Osterman’s father in the eighth episode). I think Traue’s casting actually helped convey that Agnes is a glamorous woman who hasn’t figured out how to blend in Winden yet.

Claudia Tiedemann shares her older counterpart’s heterochromia (her right eye — our left — is blue, while her left is brown). Eye colors are a consistency the show has been happy to overlook, but this is an understandable exception. For the record, none of the actresses who play Claudia — Julika Jenkins, Gwendolyn Göbel, and Lisa Kreuzer — have heterochromia.

Other Observations:

– The episode opens with a line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, “Hell is empty, and all the devils are here (Die Hölle ist leer, alle Teufel sind hier)!” It can be interpreted as a reference to the overnight materialization of the unidentified corpses, or how Ulrich doesn’t find the child murderer version of Helge in 1953, but becomes a would-be killer himself.

– The Bible doesn’t identify the weapon Cain used to kill Abel, as much as artists imagine it was something as primitive as a rock; the non-canon Book of Jasher, which is referenced in the Old Testament, describes it as the “iron part of his ploughing instrument.”

– For better or worse, the police’s surprise at the “Made in China” tags on Yasin and Erik’s clothes is one of the show’s most memorable gags. (“Chinesisch?“)

During the episode’s ending, Kreuzer’s elderly Claudia is finally seen examining the evidence wall glimpsed in the first episode. I’ll leave you to ponder our own wall of evidence until next week, when we look at “Everything is Now (Alles ist jetzt).”