One of Drawn & Quarterly’s greatest strengths as a manga publisher is their willingness to bring over the strange, the historical, and the alternate and contextualize them for audiences. One of their latest releases, Yamada Murasaki’s “Talk to My Back,” caught my eye a few months back and I’ve since gotten the chance to talk to the translator of the book, Ryan Holmberg.

Ryan is an accomplished essayist, historian, and translator and no stranger to bringing previously unknown works and artists to American audiences. Here, we drill down into Murasaki’s influence on the alt-manga sphere, on his approach to translation, and the everyday poetry she brings out in “Talk to My Back.” Without further ado, it’s with great delight that I present our conversation.

So I guess to get us started, what was the order in which “Talk to My Back” came to Drawn and Quarterly, because, as with a lot of their manga publications, there’s usually an essay in the back, especially for classics. Had you prepared that essay beforehand? Or was it something that you produced at the same time as the translation?

Ryan Holmberg: I wrote the essay specifically for that edition. But the longer story is, as you know, I had been translating and writing about alternative manga for a number of years, but almost all the artists I translated were male, so I wanted to branch out and cover female artists. Around the same time, the Honolulu Museum of Art was planning a large exhibition about women in manga. It was going to cover the history of shojo manga – manga for girls – for a younger audience and then, coming up to the present, also manga for adult women. And by “for girls,” I mean produced for and marketed to that audience, since shojo manga is in practice read by a wide variety of people.

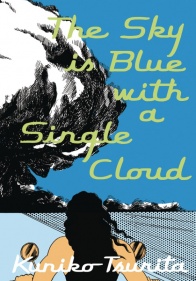

I had an association with the Honolulu Museum of Art because they had done a smaller exhibition a couple of years prior about two “Garo” artists whom I had translated: Tsuge Tadao and Katsumata Susumu. The curator, Stephen Salel, organized that exhibition and asked for advice about the new one about women and manga. I was living in Japan at the time, suggested a few artists, and helped put him in touch with a couple of them. Unfortunately, the exhibition was first suspended because of COVID, and then it was canceled, also because of a change of leadership and priorities at the museum. The exhibition catalog was completed, though never published – Stephen is looking for a new publisher now. I wrote an essay for it about “The Women of Alternative manga,” a capsule history of especially “Garo” and women artists. I wanted to translate something related to come out around the time of the exhibition, in order to support the exhibition with something concrete people could read, but also to use the exhibition as a platform to promote the book. So that’s how Tsurita Kuniko’s “Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud” came about. Have you seen that one?

Yeah, I’m actually reading it right now.

RH: I wanted to do something about Tsurita anyway, but the Honolulu exhibition seemed like the perfect opportunity since the artist’s original artwork was supposed to be in the exhibition. D&Q was also interested in publishing female alt-manga artists, so there was a lot of synergy. We’re not necessarily thinking of it as a series, but we do think it important to maintain the momentum and get more of this material out into the world.

So kind of like an initiative?

RH: Yeah, more like a focused initiative.

So, the Tsurita Kuniko was the first book and then the follow-up book was Yamada Murasaki’s “Talk to My Back.” I proposed it because I think the story is both charming and honest, and it’s easily package-able as a single volume. It’s also a continuous story rather than a series of short stories, which I’m told typically sells better. Yamada is an important artist, but oddly neglected. She’s well known in Japan, but often overlooked in manga history even in Japan because she doesn’t really fit the the general tropes of “manga by women,” something I talk about in the essay. For various reasons, she’s a representative manga artist of the 80s, both for alt-manga but also manga at large. So, if Tsurita was the representative female artist for “Garo” in the late 60s and 70s, then chronologically it made sense to do Yamada next.

Continued belowThat, at least, was my thinking. Introduce the two “Garo”-related artists who are pioneers of manga by women, but not necessarily for women, and also who don’t come out of shojo manga. Shojo manga, of course, is very popular, influential, experimental, and often deals with important and interesting issues. But there have been lots of women artists in Japan who can’t stand shojo manga and feel suffocated by the expectation that they should make work in that mode. They want to make work about issues that are relevant to their own and other women’s lives, but without having to shoehorn it into the focus on girlishness, romantic fantasy, and decorative aesthetics that traditionally define shojo manga. I feel like that’s a history that has not been represented adequately, even in Japan.

There have been other translations in English that partially reflect that other history, like Okazaki Kyoko’s books from Vertical. But even with Okazaki, as amazing and influential as she is for the history of “women’s manga,” artistically at least she’s still clearly working within a context where shojo manga is hegemonic.

Did you have to approach Drawn and Quarterly to kick off getting these licenses? Or was it something that they were pretty open to or already looking for? Like, did they come to you asking what they should do next? And you’re like, here are some licenses I think we should get.

RH: I’ve worked off and on with D&Q over the years, and much more frequently and closely since the Tsuge Yoshiharu series started, so we were already talking about potential future projects. I thought the Tsurita Kuniko book was perfect for them for various obvious reasons. It’s based on an anthology of Tsurita’s published in Japan many years ago, titled “Flight,” which was edited by Asakawa Mitsuhiro, whom I co-authored the essay with. Pitching it to D&Q was my idea, I think. I also selected what stories went into the English version, “Sky is Blue.” “Talk to My Back,” though, was definitely my idea. I first started thinking seriously about Yamada’s work while writing the essay for the Honolulu catalog.

Moving into the process of translating “Talk to My Back,” for anyone who’s never done or heard of how manga work gets translated? How does it work?

RH: Are you interested in the physical act of translating Japanese into English or how the translation gets set up as a book deal?

I guess starting with the process of taking it from the Japanese into the English and making it both understandable without losing some of the more ephemeral aspects of it.

RH: Hmm…People ask me this question sometimes and I always find it hard to answer in a broad way. I thought the translation for “Talk to My Back” was fairly straightforward because the dialogue is simple, daily-life stuff. Usually the hardest thing in cases like this isn’t knowing what the Japanese says and making it into intelligible English, but rather making it sound like believable dialogue in English. I know there are some schools of thought, particularly around manga for YA audiences, where awkward “anime English” or whatever you want to call it is the desired aesthetic. I think when it’s done well, it works and is funny and entertaining. But that’s not what I go for with my projects. I try to make it sound as much as I can like native English dialogue. Sometimes I’m successful, sometimes I’m not. There are often cultural differences you have to navigate, but that’s a different issue, since people can come from diverse cultures and still speak the same language as if it is their native language, obviously.

Wordplay and puns are some of the hardest things. Sometimes you can find solutions to translate them simply and effectively, sometimes they require a lot of explanatory notes, but since that can get unwieldy I also think, sometimes, it’s okay to prioritize readability and shed some of the specific cultural meanings. For example, there is one chapter in “Talk to My Back” titled ‘Cool Kids.’ The girls are playing with paper dolls and the paper dolls all have funny names, some of which are just silly and some slightly inappropriate for kids. I found a lot of them to be untranslatable.

Continued belowTo be honest, some of them I just didn’t understand in Japanese. I’m in touch with the artist’s daughter and I asked her what some of them meant, and even she wasn’t really sure what the exact joke was. So I translated those that I could and came up with something roughly similar to the Japanese for the rest, but with English-sounding names and silly-sounding body parts. It’s not an exact translation, but I think I at least captured the same vibe with words in the same realm of humor and meaning.

In “Talk to My Back,” there were a lot of empty balloons used for emphasis, and some of them were just filled with a few dots. Was it ever under consideration to try and fill any of those or was it like that in the original and you’re like, I’m gonna preserve that?

RH: If a speech balloon is blank in the original, you of course keep it blank in translation. Sometimes things get confusing in the process of lettering because it’s not always clear if you forgot to translate a text or if you intentionally skipped it because it’s blank in the original, which is compounded by the fact that the letterer is working with artwork where all the speech balloons are blank because the Japanese has been removed from them in order to put in the English. But that all gets sorted out in the editing process.

With ellipses, I recommend following the Japanese when possible. One thing I almost always have to flag on every project, especially when I’m working with a new publisher, or a new designer, or a new letter, is balloons with nothing but ellipses. Standalone ellipses are usually quite long in the Japanese original, with two or three lines, each of six to eight dots. That gives pauses in speech or interior thought a longer duration, and also fills out the balloon more. But often what happens in lettering the translation, the letterer will just put three dots because that’s the standard way to to write an ellipsis in English. So usually I have to go back and say you need to fill out the balloon more with more dots because not only does it look better, but it also creates a duration that suggests different things than fewer dots and a shorter duration does. Small things like that really impact the nature of dialogue and story pacing, I think.

What were what were some of your favorite chapters to translate in?

RH: Jeez. I honestly have not read the manga since sending it off the final version to print in January. When you’re producing a translation, you read every balloon multiple times, then when you’re editing, you read the entire translated book front to back probably a dozen times. And as a translator who is intimately involved with the production of the book, who even has access to the InDesign files to tweak the lettered translation, the text never stops feeling malleable. Even after the book is printed and the text is fixed, that feeling is still there to some extent. Like, “Maybe that comma would be better there rather than here.” Small micro details like that. I still don’t have the distance to look at that book from a distance. Sorry, I know that doesn’t really answer your question. What chapters did you like?

I actually really liked the paper dolls one. And I guess I kind of like the whole thing as a package. It works really well. Having a bunch of smaller chapters was also not what I was used to. Like it reads like a short story collection, but it doesn’t, which was nice.

RH: For me, one of the most memorable chapters, I think it’s a pair of chapters, were the rain ones. I think the manga is very good at capturing little daily things that have a poetic side to them and making them very visually memorable. Like walking outside in the rain barefoot and then the next day seeing the world, what was it, seeing the world upside down?

Walking on the clouds.

RH: That’s right, walking on the clouds in the puddles outside. There’s moments like that. Some of the pages also have very beautiful design. Best I think are the pages that combine strong design with what’s being narrated in the dialogue, where the poetry of word and image are mirrored in some way.

Continued belowWhat other ones?

The Chief going missing chapter.

RH: About the cat. Yeah, yeah.

I really liked how Chief doesn’t show up again. You kind of expect Chief to come back. But that’s just how life is.

You obviously did a lot of research while writing the essays, it’s very well sourced. Did you have to, while translating, supplement that with research to find out what was going on at the time? How might something have felt to these characters then versus now. And or when she was writing it versus when it was set?

RH: For a lot of the essays I write for the books I translate, I try to get away from doing too much interpretive work beyond what’s necessary to keep the narrative of the essay going. I may touch briefly on relevant historical or contemporary events to provide context. For “Talk to My Back,” I think the only time I really did that was to explain gender dynamics and middle class households in Japan, and what the term “shufu” means beyond the usual translation of simply “housewife,” which can be misleading. Obviously the manga itself deals with troubles and doubts within ideals of the middle class family, as well as what it means for a mother to go back out into the working world in Japan, which remains today, 40 years later, a very sexist and gender-segregated society. But also that’s how Yamada was framed in the press in the 1980s, as the “shufu cartoonist.” So I thought it was important to clarify some of that in the essay.

A lot of times when I translate an artist, like with Yamada Murasaki or Tsurita Kuniko, it’s the first time their work is being presenting in English, and sometimes in any language other than Japanese. So if I’m going to write an essay for a translation, I believe it is my responsibility to properly introduce them as people and artists, to provide biographical information and a survey of their career, so that people who don’t know Japan or can’t read Japanese, or who just don’t have the time to research this stuff themselves, have enough information so that they can come to their own conclusions about the artist, their world, and their work. As you can see with my essay in “Talk to My Back,” just doing that, just covering the basics, gets wordy enough. If I want to do theory or criticism or extended readings of single works or bodies of work, I can do it elsewhere.

Are you planning on, or hopefully planning on, translating more of Yamada’s work?

RH: There’s nothing set in stone now. It’s too soon to say. But we have been talking about it.

Is it weird to be doing a project like this or like “The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud,” where you’re not starting at the beginning and kind of collecting it in more completeness, like you seem to be doing with Yoshiharu Tsuge series, or is it just kind of, like, this is a great introduction to the person and their work?

RH: The Tsurita Kuniko book was designed as a career-spanning survey, while this Yamada Murasaki book is from the middle of her career. When you’re introducing a new artist, you have to assume that there might not be a sequel. You have to go in thinking that you have one chance to introduce the artist. You have to think strategically. What work will best represent the artist? But also, what work will most likely sell well enough to make the publisher, me, and the artist or their heirs happy, and well enough to perhaps inspire a second volume of their work?

In terms of writing the essays, if it’s the first time I’m writing about someone, it’s always easier to write about something that happens in the early part of their career. Because if you’re focusing on the early part of their career, you don’t necessarily have to talk about the later part in detail. However, if you’re talking about the later part of their career, especially if your goal is a kind of survey, you have to explain where they came from earlier in their career. So that is also in the back of my mind when I am choosing works to propose to publishers, though the priority is what is representative and what will sell.

Continued belowWith “Talk to My Back,” that’s sitting kind of smack dab in the middle of her career, is that her biggest work, or most well known work, in Japan?

RH: “Talk to My Back” is one of two of her most famous works. The other one is Showaru Neko, “Sassy Cats,” which slightly predates “Talk to My Back” in “Garo.” It was one of Seirindo’s (the publisher of “Garo”) best selling books in the 1980s. I think that would be worth translating. I also think it’d be worth doing an anthology of her early works from the late 60s and 70s, since they are so ahead of their time.

One last question. At the end of your essay, you talk about pushing back against one of the monikers that she was given, as being one of the “Three Daughters of Garo.” Since you didn’t put it in the essay, for the reasons you explained earlier, how do you think they should be thought of within the alt-manga sphere, within just manga in general, and within the history of the medium and women in the medium?

RH:Those three artists in particular?

Those three, but since we’re talking about “Talk to My Back” specifically, Yamada too.

RH:This is covered in the essay, but her arrival into “Garo” is important because after she started publishing in “Garo” a lot of other women artists did too, some of whom were personally associated with her. The other two “Three Daughters of Garo,” Kondo Yoko and Sugiura Hinako, actually worked as Yamada’s assistants at one point. So she was also a conduit for other women artists to publish in the magazine. She already had over 10 years of cartooning under her belt. She was a veteran at that point, so she had connections as well as the know-how to help others. Her wider contributions to manga history aside, you can understand her locally, within the history of alt-manga, as helping to open up the very male dominated world of “Garo” to more women artists. If you follow alt-manga, you probably know that “Garo” was fairly gender-inclusive by the 90s, as is its successor “Ax.” Yamada was a pioneer in that.

Her reemergence in “Garo” in the late 70s also coincides with the rise of female artists in very different spheres of manga publishing, people who were drawing for manga magazines explicitly for men, magazines where gekiga dominated, and even porn manga magazines, which had very liberal style and content policies. A number of important women artists, like Okazaki Kyoko, got their start in those kinds of magazines in the late 70s and 80s, then started writing more specifically about issues that pertain to women’s daily life in other types of magazines. That history has been told, at least in broad strokes, in the standard histories of “women’s manga” as well as that of otaku culture. But since Yamada never drew for those kind of magazines, she rarely appears in those histories. So I hope “Talk to My Back” rectifies that and helps expand our picture of the changes that happened in manga publishing and women’s cartooning in the late 70s and 80s.