While there’s been no shortage of comic adaptations of The Jungle Book, stemming either from the original Kipling stories to the Disney animated film, perhaps the most distinguishable attempts have come from P. Craig Russell. Over the course of his career, Russell has made a name for himself by translating operas, plays, fairy tales, and legends into the comics medium. These attempts have consistently produced admirable work. Now, with Disney continuing their trend of reimagining their animated classics into generally weaker live action renditions (though I’m remaining cautiously optimistic for the Jon Favreau directed 2016 remake), I thought it was as good a time as any to dig out one of Russell’s Mowgli stories and offer this commentary.

‘The King’s Ankus’ is Russell’s 19th opus, and has all the makings of a great adventure: cursed buried treasure, long forgotten cities, and ancient legends. It’s a moral fable Russell illustrates with a quick wit and playful eye; all of it coming together to show the power and reach of the medium.

Russell delivers this thing like an eccentric uncle telling an exciting story about something he witnessed while abroad. From the opening pages, the book is filled with these romantic images: a calm pond, the moon hanging the canopy of trees, and the deep mystery of the darker parts of the environment.

“It’s better in the jungle,” Kaa says after listening to Mowgli complain about his time in the man’s village. It’s constantly changing, ebbing and flowing with the tilt of the earth and the shift of the seasons. It’s a place that’s very much alive and the creatures living within are more lively because of it. This is unlike man’s village, where, as Mowgli says, “They would shut themselves up in traps, away from all the clean winds, and lay upon hard pieces of wood, and draw foul clothes over their heads, and make evil songs through their noses.”

Theres also this really sensual approach, and you can feel the excitement and energy coming from Kaa and Mowgli as they play around. Russell’s version of Kipling’s jungle is this fantastical place that’s easy to feel is actually livable.

As they’re talking, the subject changes to Kaa reflecting on one of his older adventures, where he encountered a white hood cobra in a place called the Cold Lair. Mowgli insists on going to this forgotten city because he’s never seen a white hood, and they set out. A lot of Mowgli’s motivations stem from his curiosity, and neither Kipling nor Russell punish him for it, but use it to help him see the workings of the wider world.

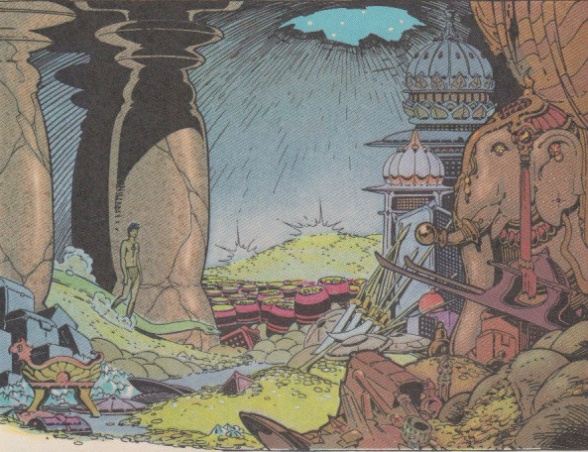

Turns out, the White Hood guards this buried treasure. He had been tasked by the Brahmins long ago to take care of that place, a responsibility the ancient creature takes very seriously. “It is not worth dying to behold?” the cobra says when he shows Mowgli to the throne room. Indeed, Russell depicts it as a wide and cavernous place, the floor covered with gold and jewels like a carpet. During this set piece, Russell always makes sure to keep the treasure somewhere in the frame, so it’s suffocating and inescapable. In this sequence, Russell also draws Mowgli most innocently and pure, I guess. He keeps Mowgli’s features softer and clearer; positions him in cross-legged poses; and has him kneel and sit as he explores the ruins.

Some context: “The King’s Ankus” originally appeared in The Second Jungle Book. In Kiping’s narrative, Mowgli did go and live in man’s village for a time. However, he rejected their customs and ways of life, their pettiness and wickedness, and he returned to his home, where he became Master of the Jungle.

Mowgli, being innocent or in tune with nature or whatever, isn’t tempted by the vast riches around him. In fact, he’s immediately drawn to the ceremonial knives, discarding each one because they lack the balance of his own blade. He picks up gold but tosses it aside. “The things here are cold,” he says, “and by no means good to eat.” Eventually, though, he stumbles on an ankus, which catches his attention because there’s a picture of someone he recognizes on it. The elephant, Hathi. His only desire is to see it out in the sun, though the cobra assumes, like all men, Mowgli wants it for its riches.

Continued belowP. Craig Russell delivers some of the best page layouts of anyone in the field. In many of his other works, he’s developed a rhythm with abnormal shapes, panels filled only with words, a sort of shadow-caster sense of movement and animation. It can be breathtaking how he can deliver a scene like Salomé’s final dance or any sequence of “The Ring of the Nibelung” or some really cool Morpheus powers. Here, he’s actually more restrained. He establishes a grid early only, and doesn’t deviate much from it. This helps maintain that bedtime storytelling nature.

Mowgli departs the lost city, not too happy with his victory over the cobra. Thuu peers out from the entrance way, proclaiming that death will be following them, that nothing will end well with that treasure out in the world. Russell delivers this in heavy black silhouettes that only hint at the doom for the second half of the story.

The second half of the story is a real gear-shift in tone, and it’s where the moral truly kicks in. Mowgli isn’t entirely sure what to do with his old prize, but when Bagheera tells him it was once used to control elephants, Mowgli throws it away in disgust and hopes to forget about it. That night, he’s plagued by these awful dreams and wakes up realizing that he must return the ankus to where it came. But it’s gone.

A group of people have stumbled on it and taken it away.

Russell delivers the Mowgli and Bagheera setpiece like a chase straight out of Indiana Jones. That black panther leaps gracefully through the foliage. Both he and Mowgli investigate all these difficult-to-reach places until they stumble across the victim of the first attack. He generates a nice momentum and forward charge as the two characters try to piece together what they’re witnessing. The whole time, the situation becomes more and more dire.

This is a book with an incredible amount of violence, but Russell (and Kipling, too), chooses to have it all occur off-panel. Humans are a concept beyond Mowgli, and that desire to kill for possessions just isn’t a thing he can comprehend. Suddenly, everything around him becomes dangerous and bizarre. The jungle has been infiltrated and infected by this evilness from the ankus. The bodies stacking up are more unsettling because we only see the aftermath of it.

Russell turns to classical art for the bodies they stumble upon. The victims are in tormented, dramatic, and tortured poses. It’s overdramatic, yes, but also truly effective since Russell really hits home how corruptible and tragic men can be. It’s kind of jarring with the tone for the rest of the book, but I think it works better for it. The classical poses also lend the events a weight and tragedy. They aren’t natural to the jungle because this mindless death isn’t natural either.

There’s definitely some easy morals to pull out of this. Greed will lead to tragic results. The past will continue to haunt the present. Know what’s going on in the world but don’t think you can upset the flow of nature. But ‘The King’s Ankus’ is definitely interesting because how little it thinks of man. The second anything of value crosses them in the story, they immediately start hacking each other apart. If the jungle is lively and warm, men are cold and hard. P. Craig Russell finds a great way to present these ideas in the comic, balancing between those and the adventuring spirit of the narrative.

Regardless of that, Russell makes sure to make the book fun. His investigative chase sequences are thrilling. The cold lair setpiece is meticulously crafted but delivered effortlessly. He has such a tight control over the direction and delivery of the story that this 25 page story both feels longer than its length but maintains a captivating and engrossing narrative that you won’t come out of until the last page. I would almost say that it’s nostalgia at work here, especially when you look at how innocent and pure Russell depicts Mowgli as opposed to the bandits in the jungle. Yet, it also feels like Kipling and Russell value curiosity, and the story constantly feels like it encourages it.

‘The King’s Ankus’ is a wonderful story, wonderfully illustrated. The P. Craig Russell comic is a fine example of a master craftsman aware of his trade and doing whatever he can to make the story work most effectively. It’s exciting and thrilling, but, most of all, marvelous to look at.