Multiversity’s history column returns with new items from the annals of the comic industry. This week’s theme is events that occurred in March.

The year 1950 was a tricky time for the company that became DC Comics. Most superheroes weren’t selling very well anymore, but management was unwilling to soil the company’s name by dealing in the popular true-crime genre that was fueling comic books’ reputation of warping children. They found enough success with romance and westerns to survive, and someone had the idea of trying to boost sales with a television tie-in.

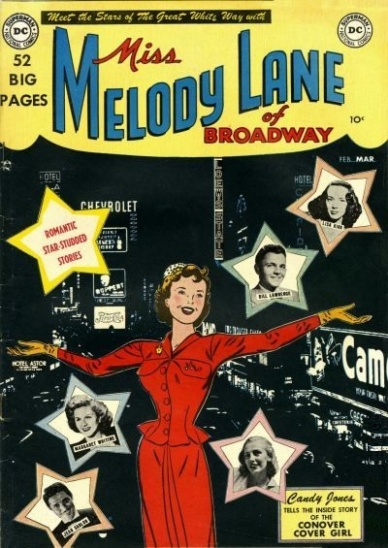

DC had previously experimented with movie tie-in comics in 1939’s aptly titled “Movie Comics,” which turned out to be the only real dud the company had ever tried. Perhaps in an effort to avoid the same woes, or in a bid to maximize the chance for success, DC decided not to go with a straightforward adaptation. Instead of choosing a single TV show for their series, they created “Miss Melody Lane.” Springing from the mind(s) of an unknown writer(s), Melody was a Broadway starlet who encountered the stars of TV shows. The first issue kicked off with a meta story about Melody temporarily becoming a cover model for DC’s comic books. Later issues featured stories with Sid Caesar and Ed Sullivan.

Unfortunately, sales on the bi-monthly “Miss Melody Lane” were abysmal. Atrocious. Abominable. I don’t have sales numbers to support that claim, but I do have other numbers. The first number is three: the number of issues the title ran before cancellation. The other number is zero: the number of other comics from DC between 1938 and 1959 that were cancelled that quickly.

The slot in the publishing schedule that “Miss Melody Lane” had occupied was filled by “Strange Adventures,” a new science fiction series that saw astronomical success.

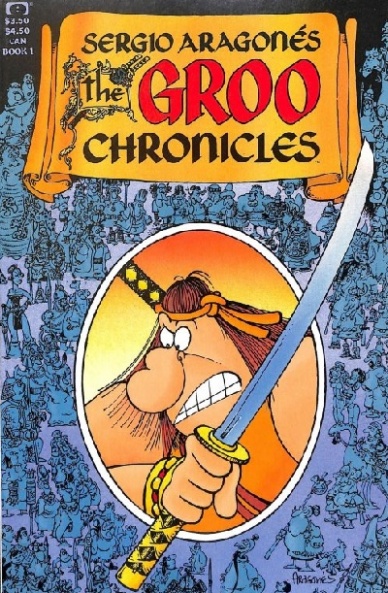

In February 1982, Sergio Aragones launched “Groo” through Pacific Comics, one of the new direct market-exclusive (DM) publishers. Pacific was good to Aragones, offering him more freedom, control, and ownership than any other publisher at the time. Their profit arrangement was also beneficial for Aragones. However, the DM exclusivity prevented Aragones’ creator-owned work from being widely available to the fanbase he had built through his years at “Mad” magazine on features like “Spy vs. Spy.”*

Over the next few years, Pacific found itself in progressively deeper financial trouble. Their struggles were known through the industry, opening the door for other publishers to woo their talent. Marvel’s response to the rapid growth of the DM was to create their Epic Comics imprint, which was an effort to combine independent publisher flexibility with the benefits of big publisher infrastructure.

With the promise of newsstand sales, Epic editor Archie Goodwin persuaded Aragones to move “Groo” away from Pacific. This was the first time a DM-exclusive property moved to the newsstands, a rare reversal of the prevailing practice at the time. “Groo” remained with Marvel for ten years and 120 issues.

*I know Aragones didn’t do Spy vs. Spy.

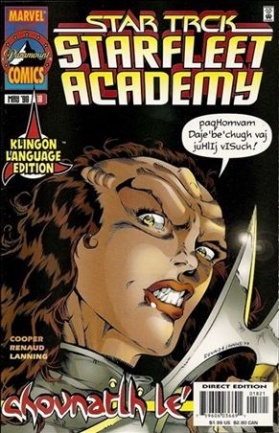

In 1998, the Star Trek renaissance was past its peak, but was still a formidable franchise. The popular “Next Generation” show had transitioned from television to films, “Deep Space Nine” was winding down, and “Voyager” was propping itself up with “Next Gen” guest stars. Through a partnership with Paramount Productions, Marvel had five ongoing “Trek” series and two miniseries, plus a plethora of one-shots and specials. One of those ongoing series was “Starfleet Academy,” which starred characters original to the comic series.

As a stunt, the 18th issue (cover dated March 1998) was published in two editions. The first was written entirely in Klingon and included a glossary for readers to reference if needed. The second, released two weeks later, was written in English. Both editions were priced at $1.99. Despite the delay for the English version, orders for it outsold the Klingon version by more than 10% (15.4k vs 13.8k).

The series, along with all of Marvel’s other “Star Trek” material, ended abruptly a month later when their deal with Paramount went sour. Trek fans would have to wait a few years to buy any new comic books, when Wildstorm got the license in 2001.

Continued belowMarch 2003

In early 2003, the US military had been active in Afghanistan for over a year and was preparing for the invasion of Iraq. Healthcare worker Tom Chafe was deployed with the Air Force and working with wounded soldiers in Kuwait. His stateside friend, Chris Tarbasian, collected comic books from friends and two local comic stores donated some of their overstock. The first package of 25-30 comics was mailed to Chafe on March 18, 2003, for use as a “diversionary activity” for soldiers under Chafe’s care.

Dubbed “Operation Comix Relief,” The story was picked up almost immediately by local (to Tarbasian) news. The MetroWest Daily ran an article about the effort on March 22. Three weeks later, the Boston Globe detailed how the effort had grown. Publishers and Diamond took note and began donating directly, boosting the size of Tarbasian’s shipments. On September 24, 2003, it was profiled in “Stars & Stripes,” a daily American Military newspaper. By October 2003, requests for comics were coming from military bases worldwide.

The organization’s website is still active, but has not been updated since 2014.

The impact was visceral, as Image dropped from being the third-largest North American comic publisher to the sixth. Without any changes to their own efforts, Dark Horse, IDW, and Dynamite all looked like they were doing much better. Of course, it was all just temporary – most of Image’s missing books returned in April (with “Image United” being a notable exception) and the company moved right back into its customary spot in third.

In an effort to broaden the public’s understanding and appreciation for military history and involvement, the US Naval Institute Press created a new imprint, Dead Reckoning, to create graphic novels about all aspects of the military. Since its first release in September 2018, it has developed a catalog 24 titles deep. All their materials are available through Diamond, although the company has yet to make a big splash in the DM. If you have a realistic (but not necessarily non-fiction) military tale you’re itching to tell, Dead Reckoning has a form for open submissions.