“Johnny Appleseed” is a wandering, rough-around-the-edges read – a dense work that puts a spotlight on a folk hero of the 19th century, and comes up with kernels of insight.

Written by Paul Buhle

Illustrated by Noah Van SciverJohn Chapman, aka Johnny Appleseed, made himself the stuff of legend by spreading the seeds of apple trees from Pennsylvania to Indiana. Along with that, he offered the seeds of nonviolence and vegetarianism, good relationships with Native Americans, and peace among the settlers. He was one of the New World’s earliest followers of the Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. The story of John Chapman operates as a counter-narrative to the glorification of violence, conquest, and prevailing notions of how the West was Won. It differentiates between the history and the half-myths of Johnny Appleseed’s life and work: His apples, for instance, were prized for many reasons, but none more so than for the making of hard cider. He was also a real estate speculator of sorts, purchasing potentially fertile but unproven acres and then planting saplings before flipping the land. Yet, he had less interest in financial gain – and yes, this is an accurate part of the mythology – than in spreading visions of peace and love. Johnny Appleseed brings this quintessentially American story to life in comics form.

As a Canadian kid (sorry), in the Canadian education system (extra sorry – all tea, all shade), I knew almost nothing about American history. Later, as an English major, I learned bits and pieces accidentally, usually as a footnote to something else. Now, as an overworked adult, I’m happy to learn anything if I’m not too tired to get my head around it. Enter an oddball book like “Johnny Appleseed” from Fantagraphics.

Centring on the figure of John Chapman – the “Johnny Appleseed” of legend who happened to be real – the book immerses you in late colonial Pennsylvania. As Buhle and Van Sciver portray it, it’s a bustling and – hmm – pretty much entirely European world, with different religious and philosophical ideas constantly attempting to come to grips with the wilderness.

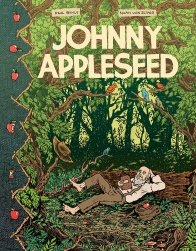

Noah Van Sciver’s black and white art establishes a rambling, brambly mood from the get-go, with loose pen strokes and heavy texture work that keep the eye busy. The forest is everywhere, sprawling across pages and pushing at the freehand panel borders. Every trunk leaning into frame is full of personality, warped and weather-beaten and strange, and close examination of any panel is bound to reveal details you missed: a falling leaf, a helpful songbird, stones bordering a path.

Chapman himself, meanwhile, is a lanky agglomeration of beard, patches, and good humour. Even with most of his face covered and not a lot of dialogue spoken, his charisma comes across through his relaxed posing. The people he encounters are similarly compelling and kindly, with small details telegraphing their character.

All through, the loose hand-lettering suits the naturalistic aesthetic, leaping and tumbling across the page. It is, however, sometimes difficult to pick out in all the texture work.

In terms of writing, Buhle’s focus is immediately on the different religious and philosophical ideas that may or may not have influenced a young John Chapman. These involve finding God in nature, or “primitive Christianity,” and non-violence – some of which later surface in the folk hero image of Johnny Appleseed, and some of which are forgotten.

Prime among all of these – to Chapman at least – is Swedenborgianism. Here we take a deep dive into the story of 18th century theologian Swedenborg himself. As Swedenborg narrates his ideas, Chapman’s reactions are intercut, making for some busy pages indeed. Mystical visions compete with natural vistas, dense crosshatching collides with rumpled leaves, and angels bro out above Swedenborg’s writing desk. It’s an exciting sequence which manages to glue lots of ideas together.

While we’re on the topic, Buhle is an academic, and his writing style is academic in every way you’d expect: tangential, piled high and deep, and tending toward long excerpts from primary sources. The depth and breadth of information is impressive, even if the large blocks of text disrupt the flow of the art.

Continued belowThis said, a weakness of Buhle’s writing is the lack of accessibility. A story playing out against a rich colonial, political, and religious backdrop requires parsed-out doses of context, but often we only get a quick, dense sidebar. Similarly, as in the Swedenborg sequence above, long excerpts from philosophical works are left to speak for themselves, when a paragraph or two of exegesis – or even a more graphics-based approach – would do a world of good.

Most detrimental to the success of the book as a whole is the vagueness surrounding the sphere of Chapman’s influence during his lifetime. While we learn about Swedenborg’s writings themselves, the nature of Chapman’s Swedenborgianism is left vague. We are told that new groups preaching non-violence, vegetarianism, and even hints of sexual liberation sprang up around Johnny; and while it’s implied he had an influence, it’s not delineated how that might have happened.

We’re on smoother ground when laying out Chapman’s posthumous ascent to folk hero status. Buhle quickly runs through how an itinerant 20th-century workforce seized on him as an icon, and he became a symbol of enterprise and individualism. Then it all falls apart again: an afterword, ostensibly about St. Francis of Assisi, breathlessly leaps from topic to topic while putting forth some of the most visually impressive pages in the book.

Overall, “Johnny Appleseed” is as patchy as its subject – wandering, rambling, and enthusiastic. Integrally, a hunk of post-colonial context is missing, making the book more valuable as a first glimpse into the time period and stepping stone to further reading.

Through it all, Van Sciver’s art gives us the wilderness – as wild, tangled, and mystical as Chapman must have felt it to be. And if there’s a lingering feeling after finishing the book, it’s of that natural splendour, bursting from every page and defying any attempt at explanation.