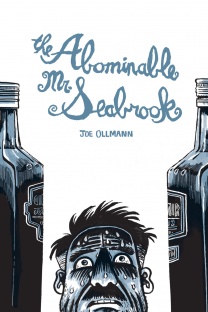

Thoroughly researched and often troubling, “The Abominable Mr. Seabrook” from Joe Ollman and Drawn & Quarterly describes a divisive – and largely forgotten – figure of the 20th century.

Written and illustrated by Joe Ollman

Journalist and travel writer William Buehler Seabrook was willing to go deeper than any outsider had before, participating in voodoo ceremonies, riding camels cross the Sahara desert, communing with cannibals and most notably, popularizing the term ‘zombie’ in the West. A string of his bestselling books show an engaged, sympathetic gentleman hoping to share these strange, hidden delights with the rest of the world. But, of course, there was a dark side. Seabrook was a barely functioning alcoholic who was deeply obsessed with bondage and the so-called mystical properties of pain and degradation. What led the popular and vivid writer to such a sad state?

(N.B.: The book’s trajectory is a lot more subtle than the solicit makes it out to be.)

William Seabrook (1884 – 1945) seems an ideal subject for biography: a notorious travel writer, a philanderer, and, ultimately, a self-destructive alcoholic. He’s adventurous, audacious, and contradictory – plenty of meaty stuff to explore. In the end, though – despite its energy and thoroughness – “The Abominable Mr. Seabrook” suffers from a lack of focus, and from an uncertain handling of its subject matter.

The first third of the biography details Seabrook’s travels to the Middle East and to Haiti, and from a narrative standpoint, they read the most smoothly. The Seabrook we meet here is a flawed charmer: enthusiastic, ingratiating, and apparently sincere in his desire to connect with different cultures, whether he ultimately succeeds or not. Ollman traces a decline from this high point, through a journey to the Ivory Coast, where Seabrook is no longer the open-minded traveller he was. Sex and booze and botched recoveries – women who support him and challenge him and enable him – all play a role in a downward spiral that ends in suicide.

Visually speaking, Ollman’s portrayal of Seabrook himself is rock-solid. He veers from grotesque – sweating, vomiting, pouchy-eyed and leering – to worldly and charming, the man who felt he could assimilate anywhere. Ollman adeptly blends the attractive and repulsive, sometimes in the same panel, and crafts a vision of a man who was many things to many people.

Storytelling-wise, Ollman takes pains to keep the large amount of information parsed and legible. Nine-panel pages make up the majority of the book – rectangular panels with doses of information. The hand-lettering sometimes gets a little small, with Ollman packing in longer and longer sentences, but it’s not too distracting an issue. All the while, background details are used judiciously, lavishly setting the scene when needed and resolving into simplicity during more emotional moments.

Generally speaking, the large cast – particularly Seabrook’s multiple wives and partners – is well-differentiated, with Ollman demonstrating a knack for character-revealing detail. Constance Kuhr, Seabrook’s last wife, is a case study in contradictory impulses, giving Seabrook truckloads of side-eye before betraying a naive aspect to her character.

However, this well-judged attitude toward detail and exaggeration falls apart during Seabrook’s travels. Which is to say: when Ollman’s subject is a wizened voodoo practitioner, or a West African chief, the line between stylish exaggeration and caricature becomes awfully uncertain. Maybe Ollman succeeds in that he immerses us so thoroughly in Seabrook’s objectifying viewpoint; and maybe any cartoonist’s portrayal of a situation so loaded with post-colonial issues is going to feel uncomfortable at best. My feeling, though, is that good intentions here are belied by uncertain execution.

More broadly, that Seabrook’s relatively progressive attitudes are used to win us over in the first part of the book winds up feeling suspect. We only know from Seabrook’s writings what his experiences were with other cultures; that we’re expected to take his word on the matter, when he may not have been accepted as deeply as he thought was, threatens to undermine the trajectory of the whole book. Was he an enlightened citizen of the world who fell from grace? Or was he always a presumptuous ass?

Seabrook’s fascination with sadomasochism is explored in fits and starts – first, as a tendency laughingly put up with by his first wife, and later, as something which estranges him from his second wife, Marjorie. It’s a complex subject treated judiciously, as an influence for good and for bad in Seabrook’s life. When he discovers a partner who shares his tastes, and participates in them joyfully, it’s a moment of sunshine, and feels like an insight into the sexual undercurrents of a conservative era. When Marjorie takes over as narrator, detailing her fears that Seabrook will really hurt somebody, it’s a terrifying window.

Continued belowOn the page, the sadomasochistic acts keep mostly to chains and collars – although it’s implied Seabrook’s actual proclivities were more extensive – and Ollman’s portrayal of these is relatively straightforward. A mention of a sex worker in chains will warrant portrayal of a sex worker in chains – usually wearing a wry expression. The effect is curiously hollow, provoking neither horror nor fascination.

Ollman explains in an endnote that he aimed to make these depictions “realistic but not sexy”, which seems a fairly safe tactic in terms of keeping up with the demands of biography without glamorizing a tendency that Seabrook occasionally took too far. (Near the end of the book, he comes close to killing a woman he hires.) And in a book filled with difficult-to-portray material, the sadomasochistic elements are likely the least problematic.

This is a biography in the end, and a biography is what it feels like – complete with sometimes-laborious detail, bits of research that are included but don’t necessarily add to the narrative. Sometimes the book feels constricted by its chronological structure; the in-between years of Seabrook’s life do not always make for great reading.

Seabrook’s alcoholism and multiple attempts at recovery form the core of his personal narrative,

and the details of his wrongdoings and relapses provoke greater and greater horror. Ollman isn’t afraid to push the grotesque here, and Seabrook’s transformation into his own zombie – a wrinkled, bug-eyed ghost of himself – is genuinely frightening. But while alcoholism is Seabrook’s central struggle, it fails to hold the book together thematically. Maybe the early and protracted emphasis on his travel writing throws the focus off; maybe it’s simply the wealth of extraneous detail.

The question that looms by the book’s end is why – why Seabrook, and in so many strokes? This isn’t to say that the book isn’t entertaining, or that Seabrook does not make a compelling figure. But there is no shortage of stories like these, even if the details are unique. This is the archetype of “The Most Interesting Man in the World”, done so thoroughly and feverishly that it feels like an elegy. The question looms: are we due for a new model of “interesting”?

This said: whether a book is worth reading is more important a question than whether it fills a void. And an answer on the former front can only be ambiguous. If you want an escapist romp, this book could be one. (But ought not to be. ) If you want a post-colonial text, this could be one. (And would make for fruitful discussion.) And if you want a narrative of self-destruction, this certainly is one – although the destruction it describes goes far beyond the self.

In terms of craftsmanship, it’s a well-thought-out comic that makes the most of the form. In any other terms, it’s difficult.